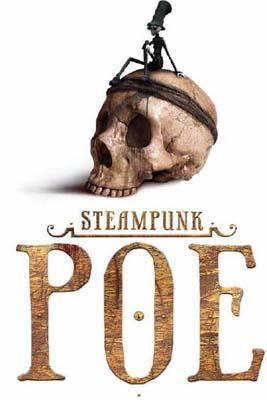

Steampunk Poe

By Edgar Allan Poe

Illustrated By Zdenko Basic and Manuel Sumberac

Introduction

The steampunk genre didnt exist when Edgar Allan Poe was penning his masterful mysteries and nightmarish horror stories, so you might be wondering how, exactly, the two have come together in this book. The greatest writers, though, produce works that transcend their own times, allowing each new generation of readers to discover them anew. And Edgar Allan Poe is nothing if not one of the greatest American writers in history.

But to understand exactly how well Edgar and steampunk go together, it might be helpful to know a little about Edgar himselfand what inspired him to write the way he did.

Edgar Poe was born on January 19, 1809, in Boston, Massachusetts. His early life was cloaked in much of the mystery and heartbreak that is woven through the canon of his works. Not long after Edgar was born, his father disappeared, abandoning the family; Edgars mother died shortly thereafter. Young Edgar was then taken in by John and Frances Allan, a wealthy family from Richmond, Virginia; though they never formally adopted him, their surname became his middle, creating a name that would earn a place in the annals of great American writers.

Edgar had a tumultuous relationship with his foster father, but that did not interfere with Johns plans for Edgars education, including a boarding school in England and enrollment in the newly-formed University of Virginia. Edgar, however, was soon expelled for debauchery that included drinking and gambling, leading to an even greater rift with John. Frances died in 1829, leaving Edgar motherless again. To honor her deathbed wish, Edgar and John tried to mend their relationship, but the reconciliation was short-lived. Despite the bad feelings between the two, Edgar never dropped the Allan from his nameeven after John eventually disowned him.

Determined to seek his fortune as a writer from an early age, Edgar returned to his hometown of Boston, where his first collection of poems, Tamerlane, was published when he was just 18 years old. Though these poems were anonymously credited to A Bostonian, Edgar was surely disappointed when his first foray into publication was met with virtually no attention. A stint in the Army, followed by enrollment at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York, offered a similar outcome to his time at the University of Virginia.

Edgar, however, was undaunted in pursuit of publication. In 1835, at the age of 26, he married his 13-year-old cousin, Virginia Clem, and moved to Fordham, New York. There Edgar made a name for himself not as a writer of original works, but as a keen literary critic, which earned him many enemies among his contemporaries. Still, with dogged determination, Edgar continued to write dozens of short stories and poems that explored his fascination with mysteries, puzzles, death, and the macabre. Especially after the death of Virginia in 1847, Edgars poems were fraught with a recurring theme of the untimely death of a beautiful young womanechoing, perhaps, Edgars own personal tragedies: the death of his mother, his foster mother, and his beloved wife. He was well-regarded among his friends and many luminaries of the literary world, despite how frequently Edgar required financial rescuing from various debts and debacles.

Poes own untimely death, at age 40, is shrouded in a mystery that perhaps only his great detective character, C. Auguste Dupin, could solve. On October 3, 1849, Edgar was found covered in filth, ill, virtually incoherentand, strangely enough, wearing clothes that did not belong to him. Though Edgar was immediately hospitalized, he never recovered, and indeed was unable to explain the bizarre circumstances that had brought him to such a sorry state of affairs. After Edgars death, several theories circulated as to the cause of his demise, including cholera, tuberculosis, alcoholism, and even rabies. It is now known that one of his most bitter literary enemies, Rufus Wilmot Griswold, worked tirelessly after Edgars death to discredit him by spreading false rumors that Edgar died of drug addiction, as well as penning a hateful obituary and a biography studded with brazen lies.

So many years after he left this earth, what remains most important is Edgars literary legacy: poems and stories that still chill and thrill with their horrifying descriptions and shocking twists, all wrapped up in evocative word choices that delight generation after generation of readers. He originated the detective story (beginning with The Murders in the Rue Morgue, The Mystery of Marie Rogt, and The Purloined Letter), and entire genres like science fiction benefited from Edgars unparalleled talent. The steampunk genre, which currently enjoys immense popularity, was decades away from invention when Edgar was writing; yet its clear how many of his stories and poems provide an essential framework for it. From Edgars interest in technological advancements like hot-air balloons in The Balloon Hoax to his elaborate descriptions of ornate architecture and lavish fashion in The Fall of the House of Usher, The Spectacles, and The Masque of the Red Death, the many charms of steampunk also serve as hallmarks of his writing. And, certainly, Edgars assorted cast of murderers and madmen offer an opportunity to explore some of the steampunk movements darker, more disturbing components. Whatever silent secrets about his life and death lie buried with him in a grave at Westminster Hall and Burying Grounds in Maryland, Edgar Allan Poes body of work continues to speak for itself.

I. Stories

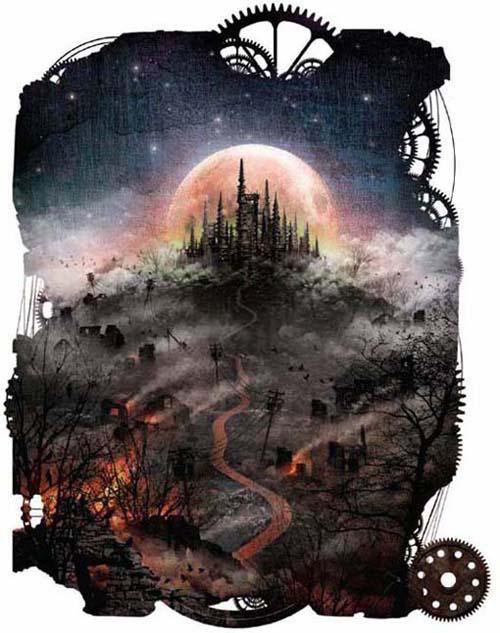

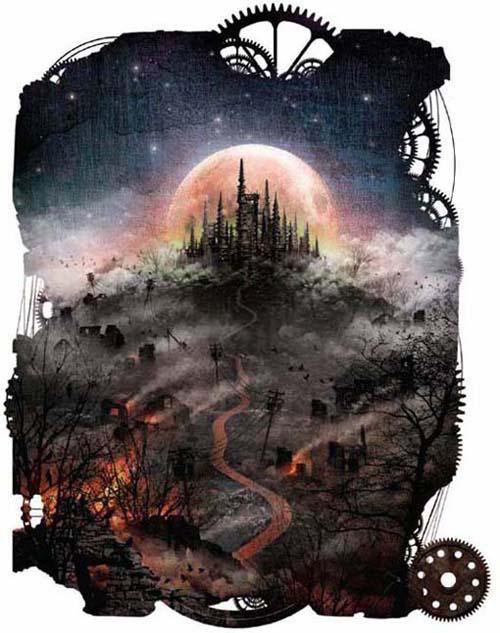

The Masque of the Red Death

THE Red Death had long devastated the country. No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous. Blood was its Avatar and its sealthe redness and the horror of blood. There were sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores, with dissolution. The scarlet stains upon the body and especially upon the face of the victim, were the pest ban which shut him out from the aid and from the sympathy of his fellow-men. And the whole seizure, progress, and termination of the disease, were the incidents of half an hour.

But the Prince Prospero was happy and dauntless and sagacious. When his dominions were half depopulated, he summoned to his presence a thousand hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court, and with these retired to the deep seclusion of one of his castellated abbeys. This was an extensive and magnificent structure, the creation of the princes own eccentric yet august taste. A strong and lofty wall girdled it in. This wall had gates of iron. The courtiers, having entered, brought furnaces and massy hammers and welded the bolts. They resolved to leave means neither of ingress nor egress to the sudden impulses of despair or of frenzy from within. The abbey was amply provisioned. With such precautions the courtiers might bid defiance to contagion. The external world could take care of itself. In the meantime it was folly to grieve, or to think. The prince had provided all the appliances of pleasure. There were buffoons, there were improvisatori, there were ballet-dancers, there were musicians, there was Beauty, there was wine. All these and security were within. Without was the Red Death.