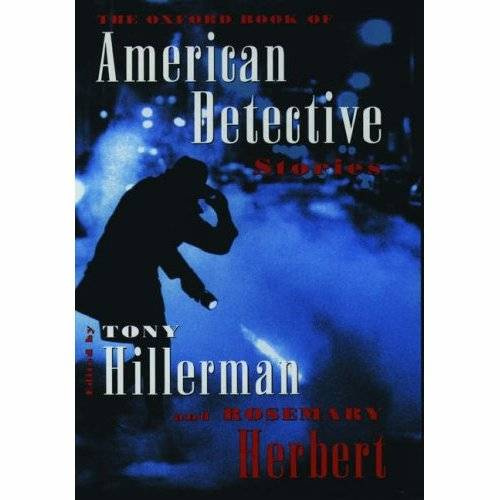

Edgar Allan Poe, Bret Harte, Jacques Futrelle, Melville Davisson Post, Anna Katharine Green, Arthur B. Reeve, Susan Glaspell, Carroll John Daly, Clinton H. Stagg, Richard Sale, Mignon G. Eberhart, Erle Stanley Gardner, Raymond Chandler, John Dickson Carr, Cornell Woolrich, Mary Roberts Rinehart, Robert Leslie Bellem, William Faulkner, Clayton Rawson, T. S. Stribling, William Campbell Gault, Anthony Boucher, Ed McBain, Ross Macdonald, Rex Stout, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Ellery Queen, Bill Pronzini, Edward D. Hoch, Linda Barnes, Sue Grafton, Tony Hillerman, Marcia Muller, Rosemary Herbert

The Oxford Book of American Detective Stories

First published in 1996

Twenty-five years ago, when I was a first novelist on a visit to my editor, I had the occasion to read the galley proofs of A Catalog of Crime, now a bible of the detective-fiction genre. My editor, who was also editing the Catalog, was called away to deal with another problem. The author of the Catalog was due to pick up his proofs, I was told. Why didn't I take a look to see if my book had made it into the volume?

I found it on page 247. The author had recommended "less routine plots" and said that "unbelievable feats of survival and retaliation by people badly wounded and haemorrhaging make the reader impatient." I checked the title page to find the author of this affront. Jacques Barzun! I knew the name: a giant of the humanities, former dean and provost of Columbia University, and author of House of the Intellect and other weighty books. Until then, I had no idea that he was also an eminent critic of detective fiction. In fact, I knew almost nothing about the field.

My ignorance was quickly dented. Barzun arrived to collect his galleys and sensed from my sullen expression that he hadn't approved my work. In the ensuing conversation, I first learned that the game I had been playing had rules, many of which I had violated.

The point of the anecdote is the purpose of this anthology. While the detective story is founded on rules that remain important today, the distinctly American "take" on these rules has vastly enriched the genre. When Rosemary Herbert and I determined to select stories that would trace the evolution of the American detective short story, we discovered that I was far from the first American author to break or bend the rules. My American predecessors had been early pioneers in playing the detective game on their own terms.

But nobody can deny that assumptions, traditions, and rules of the genre remain important. Just what are they?

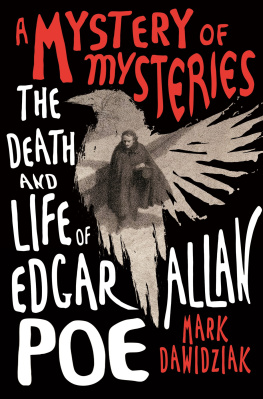

Early detective fiction was categorised as a tale rather than as serious fiction. As Barzun tells us, Edgar Allan Foe is not only the founding father and "the complete authority" on the form but also the one who "first made the point that the regular novel and the legitimate mystery will not combine."

Why not? Because in the tradition originated by the genius of Poe, the detective story emerged as a competition between writer and reader.

It was a game intended to challenge the intellect. Although Poe himself, in The Murders in the Rue Morgue, did arouse awe and horror, the major preoccupation-and innovation-in this story is the introduction of the puzzle. The reader is challenged to attempt to solve it with the clues provided. In the final pages, the reader will learn if his or her solution matches that of the detective.

Given such a purpose, the reader and writer had to be playing by the same rules. Even though the rules are rather self-evident, they were formalised by Monsignor Ronald Knox in his introduction to The Best Detective Stories of 1928. His rendition of the rules came to be known as the 'Detective Decalogue.' Perhaps because Father Knox was known as a theologian and translator of the Bible as well as a crime writer, the rules were also referred to as the 'Ten Commandments of Detective Writing.'

The rules are technical. The writer must introduce the criminal early, produce all clues found for immediate inspection by the reader, use no more than one secret room or passageway, and eschew acts of God, unknown poisons, unaccountable intuitions, helpful accidents, and so forth. Identical twins and doubles are prohibited unless the reader is prepared for them, and having the detective himself commit the crime is specifically barred. Some rules are whimsical at best or sadly indicative of the prejudices of Knox's day. Rule V, for example, provides that "no Chinaman must figure in the story." In all, the rules confirm the fact that detective stories are a game.

It is worth noting that all but one of those 'best' detective stories in the 1928 anthology were written by British authors. It was the golden age of the classic form, and though the American Poe was considered the inventor of the form, England was where the traditional side of the genre flourished. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, with Sherlock Holmes as his detective and Dr. John H. Watson as his narrator straight man, had earlier brought the detective short story to its finest flowering. And Agatha Christie polished the puzzle form, particularly in her novels, to perfection. But this volume shows that even then, things were changing in America.

As our selections show, American writers had been injecting new elements into and otherwise tinkering with Poe's classic form since the nineteenth century. Then came the 'Era of Disillusion,' which followed World War I; the cultural revolt of the 'Roaring Twenties'; the rise of organized crime and of political and police corruption, which accompanied national Prohibition; and the ensuing Great Depression. All contributed to changing the nature of American literature-with detective fiction leading the way in its recording of a distinctive American voice and its depiction of the social scene. In fact, I believe that Raymond Chandler was a greater influence on later generations of American writers-in and out of the detective genre-than was that darling of the literary establishment, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Barzun told us that the classic detective story is written by and for the educated upper-middle classes. Particularly in the British manifestation, it was typically set in upper-crust milieus. But we've chosen Susan Glaspell to demonstrate that in an American writer's hands, the story can also succeed in a remote, rural farmhouse literally in the middle of America. Glaspell's story A Jury of Her Peers also proves that social concerns like wife battering can be used to evoke an emotional reaction on the part of the reader, even while the puzzle element remains central.

While in Britain readers were puzzling over whodunit in stories sold at railway stations, in the United States the newspaper stands and drugstore magazine racks held detective fiction of a different sort-published in pulp magazines with garish covers and cheap prices. One of these was Black Mask, and one who wrote for it was a former Pinkerton private detective named Dashiell Hammett.

Like many of his fellow American producers of detective fiction, Hammett was definitely not an effete product of the upper or even solidly middle class. Neither were the settings of his stories nor the characters who populated them. He and other American crime writers during the Depression years were taking crime out of the drawing rooms of country houses and putting it back on the 'mean streets' where it was actually happening.

This is not to say that the classic form was dead or even ailing. Early examples in this volume are the work of Bret Harte and Jacques Futrelle. Harte, known for his depictions of American life in Gold Rush territory, could turn his hand to writing the quintessential Sherlockian pastiche: The Stolen Cigar Case. And Jacques Futrelle's The Problem of Cell 13 obeys all the rules of the locked-room mystery with a character locked into a high-security 'death cell' in an American prison.

Next page