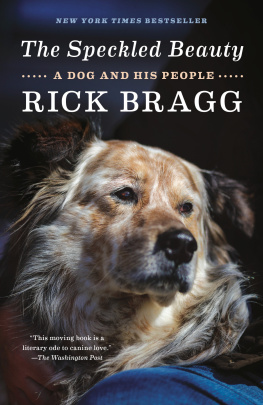

Rick Bragg

ALL

OVER BUT

THE SHOUTIN

Rick Bragg is the author of Somebody Told Me, All Over but the Shoutin and Avas Man. A national correspondent for The New York Times , he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing in 1996. He lives in New Orleans.

FIRST VINTAGE EDITION, SEPTEMBER 1998

Copyright 1997 by Rick Bragg

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1997.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: EMI Music Publishing: Excerpt from I Been to Georgia on a Fast Train by Billy Joe Shaver. Copyright 1972 by Sony/ATV Songs LLC. Administered by EMI Blackwood Music Inc. (BMI). All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Reprinted by permission of EMI Music Publishing. MCA Music Publishing: Excerpt from The Great Speckled Bird by Guy Smith. Copyright 1937, 1964 by MCA-Duchess Music Corporation. Copyright renewed. Duchess Music Corporation is an MCA Company. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of MCA Music Publishing. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc.: Excerpt from Im So Lonesome I Could Cry by Hank Williams. Copyright 1949 (renewed) by Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. and Hiriam Music for the U.S.A. World outside of U.S.A. controlled by Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. Excerpt from Pancho and Lefty by Townes Van Zandt. Copyright 1972 by Columbine Music & EMI U Catalog Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Pantheon edition as follows: Bragg, Rick.

All over but the shoutin / Rick Bragg. p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76291-7

1. Bragg, Rick. 2. Bragg, RickChildhood and youth. 3. JournalistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Working class whitesAlabamaBiography. 5. AlabamaBiography. 6. AlabamaRural conditions. I. Title PN4874.B6625A3 1997 070.92dc21

[B] 97-9918

Author photograph Marion Ettlinger

Random House Web address: www.randomhouse.com

v3.1_r1

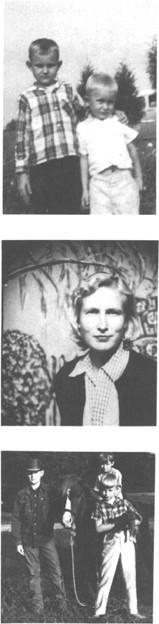

T O MY MOMMA

AND MY BROTHERS

Contents

Living on the road my friend Was gonna keep you free and clean Now you wear your skin like iron And your breath is hard as kerosene You werent your mommas only boy But her favorite one, it seems She began to cry when you said goodbye Saddled to your dreams

T. V AN Z ANDT

Prologue

Redbirds

I used to stand amazed and watch the redbirds fight. They would flash and flutter like scraps of burning rags through a sky unbelievably blue, swirling, soaring, plummeting. On the ground they were a blur of feathers, stabbing for each others eyes. I have seen grown men stop what they were doing, stop pulling corn or lift their head out from under the hood of a broken-down car, to watch it. Once, when I was little, I watched one of the birds attack its own reflection in the side mirror of a truck. It hurled its body again and again against that unyielding image, until it pecked a crack in the glass, until the whole mirror was smeared with blood. It was as if the bird hated what it saw there, and discovered too late that all it was seeing was itself. I asked an old man who worked for my uncle Ed, a snuff-dipping man named Charlie Bivens, why he reckoned that bird did that. He told me it was just its nature.

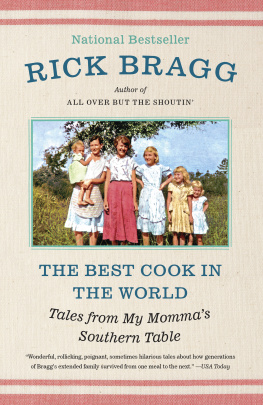

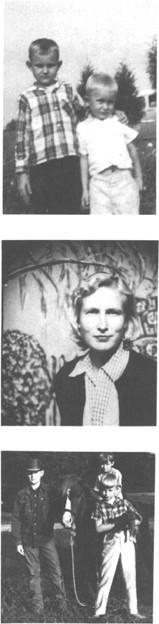

T his is not an important book. It is only the story of a strong woman, a tortured man and three sons who lived hemmed in by thin cotton and ragged history in northeastern Alabama, in a time when blacks and whites found reason to hate each other and a whole lot of people could not stand themselves. Anyone could tell it, anyone with a daddy who let his finer nature slip away from him during an icebound war in Korea, who allowed the devil inside him to come grinnin out every time a sip of whiskey trickled in, who finally just abandoned his young wife and sons to the pity of their kin and to the well-meaning neighbors who came bearing boxes of throwaway clothes.

Anyone could tell it, anyone who had a momma who went eighteen years without a new dress so that her sons could have school clothes, who picked cotton in other peoples fields and ironed other peoples clothes and cleaned the mess in other peoples houses, so that her children didnt have to live on welfare alone, so that one of them could climb up her backbone and escape the poverty and hopelessness that ringed them, free and clean.

Anyone could tell it, and thats the shame of it. A lot of women stood with babies on their hips in line for commodity cheese and peanut butter. A lot of men were damaged deep inside by the killing and dying of wars, then tried to heal themselves with a snake oil elixir of sour mash and self-loathing. A lot of families just came to pieces in that time and place and condition, like paper lace in a summer rain. You can walk the main street in any small town, in any big one, and you will hear this story being told behind cigarette-scarred bars, before altars, over fresh-dug ground in a thousand cemeteries. You hear it from the sixty-five-year-old woman with the blank eyes who wipes the tables at the Waffle House, and by the used-up men with Winstons dangling from their lips who absently, rhythmically swing their swingblades at the tall weeds out behind the city jail.

This story is important only to me and a few people who lived it, people with my last name. I tell it because there should be a record of my mommas sacrifice even if it means unleashing ghosts, because it is one of the few ways I can think ofbeyond financing her new false teeth and making sure the rest of her life is without the deprivations of her pastto repay her for all the suffering and indignity she absorbed for us, for me. And I tell it because I can, because it is how I earn my paycheck, now at the New York Times , before at so many other places, telling stories. It is easy to tell a strangers story; I didnt know if I had the guts to tell my own.

This is no sob story. While you will read words laced with bitterness and killing anger and vicious envy, words of violence and sadness and, hopefully, dark humor, you will not read much whining. Not on her part, certainly, because she does not know how.

I have been putting this off for ten years, because it was personal, because dreaming backwards can carry a man through some dark rooms where the walls seem lined with razor blades. I put it off and put it off until finally something happened to scare me, to hurry me, to make me grit my teeth and remember.

It was death that made me hurry, but not my fathers. He died twenty years ago, tubercular, his insides pickled by whiskey and beer. Being of long memory, my momma, my brothers and I did not go to the cemetery to sing hymns or see him remanded to the red clay. We placed no flowers on his grave. Our momma went alone to the funeral home one night, when it was just him and her.

No, the death that made me finally sit down to write was that of my grandmother, my mothers mother, Ava, whom we all called by her pet name, Abigail. Miss Ab, who after enduring eighty-six years of this life and a second childhood that I truly believed would last forever, died of pneumonia two days before Thanksgiving, 1994. The night her grown children gathered around her bed in the small community hospital in Calhoun County, Alabama, I was in New Orleans, writing about the deaths of strangers.

Next page