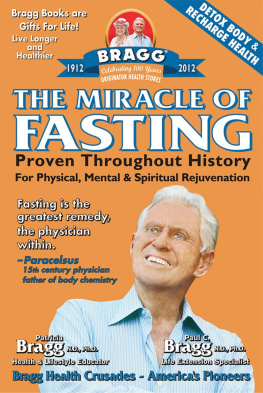

I Am a Soldier, Too

The Jessica Lynch Story

RICK BRAGG

Alfred A. Knopf New York 2003

New York 2003

Contents

This book is dedicated to the memory of

Private First Class Lori Piestewa,

Jessicas friend and protector, who was killed

in the ambush at Nasiriyah on March 23, 2003.

It is also dedicated to the memories of the other

ten soldiers who lost their lives in the ambush:

Specialist Jamaal Addison

Specialist Edward Anguiano

Sergeant George Buggs

First Sergeant Robert Dowdy

Private Ruben Estrella-Soto

Private First Class Howard Johnson II

Specialist James Kiehl

Chief Warrant Officer Johnny Villareal Mata

Private Brandon U. Sloan

Sergeant Donald R. Walters

I Am a Soldier, Too

Introduction

Hero

On most nights of the year, this stretch of country road is only a flat place in the dark. But for a few nights in late summer 2003, it blazed in neon, smelled like smoked sausage, spun sugar and blue-ribbon hogs, and rang with screams of people who had bought a ticket to be scared. They rode the Tilt-A-Whirl, browsed tents of prizewinning fruit preserves and lined up for the cute-baby contest, and if there is such a thing as a time machine on earth, it must be powered by the Ferris wheel at the Wirt County, West Virginia, Fair. Back from the war, Jessica Lynch asked her mother and father to take her there.

She went every year until she left for the army, said Dee Lynch, Jessis mother. She would meet her friendseverybody knew everybody. Its just a little county fair. You could sit at one end of the thing and watch your kids play at the other end. It never changed.

The ping and rattle of the rides and games reached all the way to the parking lot as Greg Lynch pushed Jessis wheelchair toward the glow of the midway, over ruts that jostled her legs (which had been repaired with a metal rod and a screw), her pieced-together arm and her back, which had been realigned with metal plates.

But she was sick of lying in her adjustable bed at home. It was her first real public appearance, her mother said. She wanted to see the cute-baby contest, but we never got that far.

It started with a polite, shy inquiry from an old man.

Maam, can my wife stand by you while I take a picture?

And in secondsnot minutes, but secondsJessi was surrounded by people who just wanted to touch her, to say hello, or just to look at her. The word trickled through the crowdJessis hereand there was no way to move the wheelchair one inch farther.

Can I sit my child on your lap? one woman said, and then another asked, and another. The cameras flashed and old women hugged her shoulders or said Bless your heart. A little girl asked, Mommy, is that the girl from TV? One old man told her he had lost two sons and had given up on living, but her story made him ashamed to give up.

It was real nice and stuff, Jessi said.

Over and over again, they said the same thing to her.

Youre a hero.

The word bounced from person to person.

Hero.

An hour passed, the wheels of her chair locked in a circle of adoring people.

Hero.

It was weird, Jessi said later, sitting at her kitchen table, her pain medication lined up in front of her beside a glass of chocolate milk. The very word makes her sad. For twenty years, no one knew my name. Now they want my autograph. But Im not a hero. If it makes people feel good to say it, then Im glad. But Im not. Im just a survivor. When I think about it, it keeps me awake at night.

One

The Deadliest Day

SOUTHERN IRAQ

March 2003

The recruiter said she would travel. Now, twenty months after enlistment, nineteen-year-old Private First Class Jessica Lynch steered her groaning diesel truck across a hateful landscape of grating sand and sucking mud, hauling four hundred gallons of water in the rough direction of Baghdad on a mission that just felt bad. Back home, boys with tears in their eyes had offered to marry her, to build her a brand-new house, anything, to get her to stay forever in the high, green lonesome. She told them no, told them she was going to see the world.

But the recruiter had not told any lies. He offered her a way to make some money for college, so that, when this hitch was over, she could become the kindergarten teacher she wanted to be. And he offered a way to escape the inertia of the West Virginia hills, a place so beautiful that a young person can forget, sometimes until she is very old, that she is standing still. In the process, she would serve her country, something people in her part of America still say without worrying that someone will roll his eyes.

She bought it. They all had, pretty much: all the soldiers around her, the sons and daughters of endangered blue-collar workers, immigrant families and single mothersa United States Army borrowed from tract houses, brick ranchers and back roads. The not-quite beneficiaries of trickle-down economics, they had traded uncertain futures for dead-certain paychecks and a place in the adventure that they had heard their ancestors talk of as theyd twisted wrenches, pounded IBM Selectrics and packed lunches for the plants that closed their doors before the next generation could build a life from them.

The military never closed its doors, and service was passed down like a gold pocket watch. Sometimes it was a good safe bet, all beer gardens and G.I. Bills, and sometimes it was snake eyes, and the soldiers found themselves at a Chosin Reservoir, or a Hue, or on a wrong turn to An Nasiriyah.

As the convoy of big diesels waddled across the sand, the world she saw was flat, dull and yellow-brown, except where the water had turned the dust to reddish paste. She got excited when she saw a tree. Trees made sense. She had grown up in the woods, where solid walls of hardwood had sunk roots deep into the hillsides and kept the ground pulled tight, as it should be, to the planet. All this empty space and loose, shifting sand unsettled her mind and made her feel lost, long before she found out it was true.

She was afraid. The big trucks had been breaking down since they left the base in Kuwait, giving in to the grit that ate at the moving parts or bogging down in the mud and sand like wallowing cows. Her convoy, part of the 507th Maintenance Company deployed from Fort Bliss, Texas, was at the tail end of a massive supply line that stretched from the Kuwaiti border through southern Iraq, a caravan loaded with food, fuel, water, spare parts and toilet paper. Her convoy followed the route that had already been rutted or churned up by the columns ahead, and every time a five-ton truck hit a soft place and bottomed out, the thirty-three vehicles in Jessicas convoy dropped farther behind.

Jessica just remembers a foreboding, a feeling that the convoy was staggering into enemy country without purpose or direction. Two days into the mission, the convoy had dropped so far behind that it had lost radio contact with the rest of the column. One of the far-ahead convoys carried her boyfriend, Sergeant Ruben Contreras, who had promised he would look after her. The day they left Kuwait, his column had pulled out just ahead of hersin plain view. Now he had vanished in the distance along with the rest.

The convoy shrank every day as the heavy trucks just sank into the sand and came apart. In just two days, the thirty-three vehicles in the convoy had dwindled to eighteen, and two of them were being towed by wreckers. One day, it took five hours to lurch just nine miles. To make up that distance and time, the soldiers in the 507th slept little or not at all. They were cooks, clerks and mechanics, none of them tested in combat. They became bone weary and sleepwalked through the days.

Next page

New York 2003

New York 2003