A LSO BY R ICK B RAGG

My Southern Journey: True Stories from the Heart of the South

Jerry Lee Lewis: His Own Story

The Most They Ever Had

The Prince of Frogtown

I Am a Soldier, Too: The Jessica Lynch Story

Avas Man

Somebody Told Me: The Newspaper Stories of Rick Bragg

All Over but the Shoutin

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A . KNOPF

Copyright 2018 by Rick Bragg

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Peer International Corporation for permission to reprint an excerpt of Waiting For A Train by Jimmie Rodgers, copyright 1929 by Peer International Corporation, copyright renewed. Reprinted by permission of Peer International Corporation. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bragg, Rick, author.

Title: The best cook in the world / by Rick Bragg.

Description: New York : Alfred A. Knopf, [2018] | A Borzoi Book.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017024979 (print) | LCCN 2017028840 (ebook) | ISBN

9780525520283 (ebook) | ISBN 9781400040414 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Bragg, Rick,family. | Cooking, AmericanSouthern style. |

LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX 715.2. S 68 (ebook) | LCC TX 715.2. S 68 B 725 2018 (print) |

DDC 641.5975dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017024979

Ebook ISBN9780525520283

Cover design Stephanie Ross

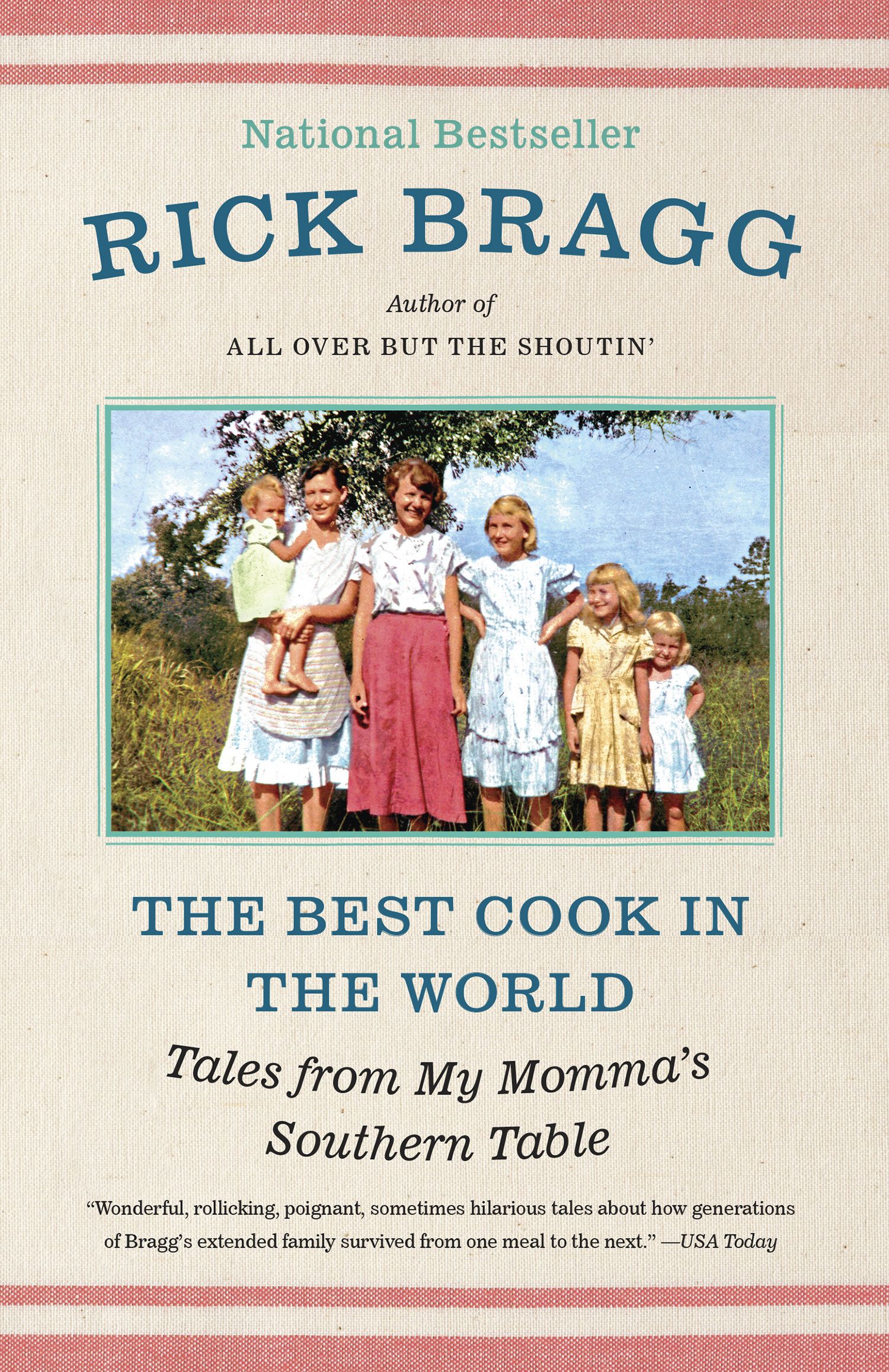

Cover photograph courtesy of the author. Colorization by Dana Keller

v5.2_r4

ep

To the cook

Contents

Let your speech be always with grace, seasoned with salt, that ye may know how ye ought to answer every man.

COLOSSIANS 4:6

Good stuff always has a story.

MARGARET BRAGG

PROLOGUE

IT TAKES A LOT OF RUST TO WIPE AWAY A GENERAL ELECTRIC

Three generations of great cooks, from left to right: Great-Aunt Plumer, Aunt Juanita, Cousin Mary, Cousin Betty, Aunt Edna, my mother at 13, Cousin Louise, Aunt Jo, Cousin Norma Jean, Grandmother Ava, Aunt Sue, Aunt Fene, and Cousin Jeanette in diapers

SINCE SHE WAS eleven years old, even if all she had to work with was neck bones, peppergrass, or poke salad, she put good food on a plate. She cooked for dead-broke uncles, hungover brothers, shade-tree mechanics, faith healers, dice shooters, hairdressers, pipe fitters, crop dusters, high-steel walkers, and well diggers. She cooked for ironworkers, Avon ladies, highway patrolmen, sweatshop seamstresses, fortune-tellers, coal haulers, dirt-track daredevils, and dime-store girls. She cooked for lost souls stumbling home from Aunt Hatties beer joint, and for singing cowboys on the AM radio. She cooked, in her first eighty years, more than seventy thousand meals, as basic as hot buttered biscuits with pear preserves or muscadine jelly, as exotic as tender braised beef tripe in white milk gravy, in kitchens where the only ventilation was the banging of the screen door. She cooked for people shed just as soon have poisoned, and for the loves of her life.

She cooked for the rich ladies in town, melting beef short ribs into potatoes and Spanish onions, another womans baby on her hip, and sleepwalked home to feed her own boys home-canned blackberries dusted with sugar as a late-night snack. She pan-fried chicken in Reds Barbecue with a crust so crisp and thin it was mostly in the imagination, and deep-fried fresh bream and crappie and hush puppies redolent with green onion and government cheese. She seasoned pinto beans with ham bone and baked cracklin cornbread for old women who had tugged a pick sack, and stewed fat spareribs in creamy butter beans that truck drivers would brag on three thousand miles from home. She spiked collard greens with cane sugar and hot pepper for old men who had fought the Hun on the Hindenburg Line, and simmered chicken and dumplings for mill workers with cotton lint still stuck in their hair. She fried thin apple pies in white butter and cinnamon for pretty young women with bus tickets out of this one-horse town, and baked sweet-potato cobbler for the grimy pipe fitters and dusty bricklayers they left behind. She cooked for big-haired waitresses at the Fuzzy Duck Lounge, shiny-eyed pilgrims at the Congregational Holiness summer campground, and crew-cut teenage boys who read comic books beside her banana pudding, then embarked for Vietnam.

She cooked, most of all, to make it taste good, to make every chipped melamine plate a poor mans banquet, because how do you serve dull food to people such as this? She became famous for it, became the best cook in the world, if the world ends just this side of Cedartown. But she never used a cookbook, not in her whole life. She never cooked from a written recipe of any kind, and never wrote down one of her own. She cooked with ghosts at her sure right hand, and you can believe that or not. The people who taught her the secrets of Southern, blue-collar cooking are all gone now, and they did not cook from a book, either; most of them did not even know how to read and write. Every time the old woman stepped from her workshop of steel spoons, iron skillets, and blackened pots, all she knew about the food left with her, in the way, when a bird flies off a wire, it leaves only a black line on the sky.

Its all Ive ever been real good at, and people always bragged on my cookingyou know, cept the ones who dont know whats good, she told me when I asked her about her craft. When I was little, the old women used to sit in their kitchens at them old Formica tables and drink coffee and tell their fortunes and talk and talk and talk, about their sorry old men and their good food and the good Lord, and they would cook, myGod, they could cook.And I just paid attention, and I done what they done.

Most chefs, when asked for a blueprint of their food, would only have to reach for a dog-eared notebook or a faded handwritten index card for ingredients, measures, cooking times, and the rest.

I am not a chef, she said.

Yet she can tell if her flour is getting stale by rubbing it in her fingers.

I am a cook.

I remember one night, when she was yearning for something sweet, she patted out tiny biscuits and plopped them down in a pool of milk flavored with sugar, cinnamon, vanilla, and cubes of cold butter. She baked this until the liquid, half whole milk, half thick, sweetened condensed milk, steamed into the biscuits, infusing them with the flavors underneath. It created not a dense slab, like a traditional, New Orleansstyle bread pudding, but little islands of perfect sweet, buttery dumplings; the spacing, not the ingredients or cooking time, was the secret here. Momma taught it to me, and Grandpa Bundrum taught it to her, and his momma taught it to him, andwell, I guess I dont really know no further than that.