CONTENTS

About the Book

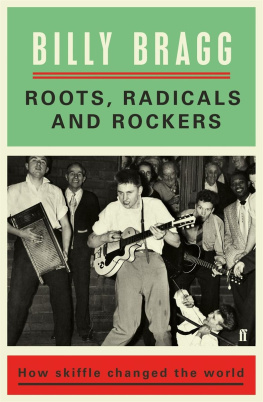

He was a punk. He was a soldier. He was a flag-waver for both the Labour Party and the miners. He is Billy Bragg, best known as a passionate protest folk singer and a tireless promoter of political and humanitarian causes all across the world.

His life encapsulates so much about his generation: born in the late 50s, passions forged by punk, politics shaped by Thatcherism, hope provided by what he sees as a post-ideological twenty-first century. Serious about compassion and accountability, he likes a laugh too, and is enduringly popular.

Billy Bragg remains to this day a much-loved songwriter and performer whose campaigning has now spanned four decades and shows no sign of relenting. Still Suitable For Miners is his official story, updated for the 30th anniversary of his debut album, Lifes a Riot with Spy Vs Spy, and including the recording of his tenth album as a solo artist, Tooth and Nail.

About the Author

Andrew Collins is a writer and broadcaster. Having worked for NME, Empire and Q, he regularly broadcasts on Radio 2, Radio 4 and 6 Music. He is Film Editor of Radio Times co-writer of BBC sitcoms Grass and Not Going Out, and author of Where Did It All Go Right? and Heaven Knows Im Miserable Now.

This book is dedicated to two people: Julie Quirke, for showing me heaven, and Reg Ward, my grandfather, for political inspiration.

FOREWORD

THE FIRST TIME that I ever got to sit alone with Paul Weller was at the Solid Bond Studios sometime in 1984. While we discussed life, the universe and everything, his hands were busily occupied with cutting articles about himself out of newspapers and magazines and filing them away for his scrapbook. It impressed me greatly that, although arguably one of Britains premier pop stars, he still did his own chores. I also felt a sense of relief that someone whom I admired so much might feel the same way that I did about preserving material, to the extent that he felt it was not a job he could safely entrust to someone else.

When I began to get notices in the papers, I would buy two or three copies, not so much from self-obsession, more to check that they were actually saying something about me in every copy. That sense of disbelief wore off after a couple of years, but I still kept my cuttings and tour passes and itineraries. It would have been better to keep a diary you might think, but with a diary you need time for reflection and then even more time to get your thoughts down clearly. And I just didnt have that time, nor those clear thoughts. I was tearing round the world, returning to my flat in West London only to check my mail and empty my bags. The place filled up with what I can only characterise as stuff, junk that I hung on to for the sake of posterity. And one day posterity knocked on my door in the shape of Andrew Collins.

I had been approached by a few would-be biographers in the past but they were mostly earnest young men who I feared would portray me as some working-class hero whose life had been one long hard struggle. These were the same kind of people who described my friends as being a bit lumpen. Andrew at least knew enough about me to realise that the personal was at least as important as the political, and that my life was a mess of contradictions rather than a shining path of political correctness. A feature he wrote in Q magazine convinced me he was the right person for the job. He had astutely taken a number of minor events in my career and threaded them together as a series of epiphanies. It was informative and insightful but, better than that, it was entertaining.

With an impeccable sense of timing, he began this project just as I started the long process of emptying my flat and fifteen years worth of stuff started raining down on him (the rest was at my mums. He helped me load it in to the back of my car). A nice young couple are now ensconced in my old place and a considerable amount of junk has been divided up between my attic, the local charity shops, the town dump and a lock-up in Acton Vale. But not before Andrew had had a chance to pore over it, just for the sake of posterity.

This leaves me with a lot of empty shelf space to stare at, but, as I write, Pete Jenner is concocting another tour itinerary for me, with, hopefully, that precious day off after Plymouth, and I feel that it can only be a matter of time before my living space attains once more the fabulous clutter to which I am accustomed.

Thanks to all my dear friends who took the time to contribute their thoughts and memories to this book and to Andrew Collins for matching my sense of history with his sense of humour.

Billy Bragg, 1998

PREFACE: HOW DID I GET HERE?

This bloke, 19572013

AS A CAT who was wiser than he looked once sang, you wont fool the children of the revolution. Tragically, the sloppy workmanship of a garage in Sheen killed the cat in 1977. As a result, he never lived to see how the children of Britains newest revolution would turn out.

They turned out just fine.

Punk rock was, for those who lived through it and came out permanently scathed, far more than a musical movement or a collection of diminishing guitar bands. For certain art-schooled agents provocateurs in London it was a situationist joke, but a good one, and a long one. For kids in the provinces and faraway towns, it was a clarion call. For a group of journalists in the right place at the right time, it was day one of a job-for-life. For the huddled wannabe masses still in the dark after Shine On You Crazy Diamond, it was all the excuse they needed to stop miming with a racket and start making one.

For Stephen William Bragg, exiled in Essex, punk was the flame that lit his fireworks; it was all the excuse he needed to change his name to Billy Bonkers and take in those Lionels. (Lionel Blairs: flares. An example of hand-me-down Cockney rhyming slang forged in those far-off days when the grinning Palladium hoofer was the first Blair who came to mind. Funny.) On 9 May 1977, the nineteen-year-old Billy and his gang, from the relative safety of the Finsbury Park Rainbow balcony, witnessed the sleeveless fury and airborne masonry of the White Riot tour. Realising that The Clash were just a tighter, younger, sexier Rolling Stones using the same amps, throwing the same shapes Billy never looked back.

The cleansing fires of punk. This poetic notion arises again and again when you talk to or read about Billy Bragg, almost as frequently as reference to Lionels. Now in his forties, just like Strummer and Weller and Rotten, Billy is a textbook child of the revolution, born just three years after rationing was finally phased out in Britain, a year after that business in Suez, and halfway through a thirteen-year Tory administration that would eventually end not with a landslide but a polite cough. Anything could happen, but not much did.

Theyd never had it so good, in the immortal words of Harold Macmillan (Prime Minister as superhero, thanks to Evening Standard cartoonist Vicky). Sure, out there in the Arts, down at the newly concreted South Bank, the Young Men were a trifle Angry but in the real world of the latter 1950s and early 1960s, Britain felt fine: three television channels, full employment, Hancocks Half Hour and a staggering range of soap powders that washed whiter than white.

The decade rapidly deemed swinging was one of insular national pride, of Merseybeat, Twiggy and Bobby Moore. A knockback by de Gaulle when Britain first tried to join the Common Market in 1961 served only to heighten its island mentality. In 1964 Labour scraped in, under Harold Wilson, but little changed on the landscape.

Next page