Keep yourself in the best of company, and your horse in the worst.

RACING WISDOM

1 And Hes Off!

ON THE FIRST Saturday that May, Hastings Racecourse feels as festive as a can of mushroom soup. Under a low-pressure system, the careworn racetrack is almost fullif youre seeing double. Im perched on a park bench on the outer lip of the undersized dirt track, opposite the tote board, which tallies bets and odds and post times in blinking lights, next to the infields duck pond. Right now, the actual racing oval sits empty during an extended intermission in the card while the Kentucky Derby is being contested kitty-corner across the continent.

From the bleacher seats in the grandstand, painted the same military green as the barns in the distance, a conga line of bachelor party attendees, toting wallet chains and tribal tattoos with their turned-brim fedoras and Hawaiian shirts, the body spray wafting in their wake like a propane leak, tumble down the aisle to the beer tent. They pass the box seats reserved for the families of the owners, the faux-jolly lumber magnates in jeans and windbreakers. Outdoors, I conclude, is for the few youthful poseurs present today.

Id gladly lump myself with the railbirds, the silver-haired punters, who are all watching the real action onscreen in one of the dozens of simulcast screens playing in the grandstand basement. The stout, moustache-bearing guy next to me, who smells more of coffee than beer or mint julep, is chatty like an expectant daddy. When our eyes meet looking down from the screen, he taps his program. Ive got seven keyed to four, five, and fifteen on a triactor, he says proudly. The seven-horse came off the pace to win in Arkansas three weeks ago.

I bet on seven, too, I admit reluctantly, knowing it will feed our bond. (Mutuel betting at the racetrack means our fortunes will be won from or lost to those who bet on other horses. Like poker, gamblers play against each other and not the house, which only pulls in a rake.) Its been a while since Ive had a good day.

I hear you, he says. Last time I got lucky was the seventies. I was at the border with an ounce of hash in a Thermos and they searched the car ahead of me.

Why do you keep coming back? I ask.

He shrugs. Every day is new.

As the horses are escorted into the gates, I step away and blend back into the crowd. Planted there, we cock back our heads like were at the dentists, making polygonal, root-canal faces as we clutch our mutuel tickets. On that Saturday that May, 153,563 people in Louisville are packed together, in the stands and infield at Churchill Downs, to watch million-dollar racehorses run for two minutes. As I look around, the crowd isnt nearly as drunk, as event-attired, or as hyped-up as the people at the Derby. On the plus side, no one in this half-filled track can be seen publicly urinating.

If anyones making a puddle around me, its because of prostate surgery. After all, the primary demographic at Hastings Racecourse is old and male, equal parts white or Asian, plus a sprinkling of men who mutter to themselves in nicotine-scorched Caribbean English. In their fraying argyle sweaters, their tweed blazers and baseball caps, their sensible sneakers and fanny packs, these horseplayers squint away at their copies of the Daily Racing Form, cross out the low-paying favourites from their copies of the racing programwhich details the performance history of every contestant, equine and man, from a trainers winning percentage to a horses prize earningswith emphatic Xs, and sift through the shifting onscreen odds. All of them take one collective gasp as the horses onscreen pop out of the gates like corks from champagne bottles.

For most of the broadcast, the pacesetter is a horse named Regal Ransom. Its only at the top of the stretch that another three-year-old called Mine That Bird threads his way to the rail and begins to pull away from the pack. The announcer for the NBC broadcast seems to disregard the 50-to-1 long shot until, in the final stretch, when his victory is nearly cemented, he takes notice and his voice rises abruptly like an airbag that inflates two beats after fatal impact.

It should be an exciting finale, but all those around me groan as their wagers are snuffed out. You think that horse even knows it won? says the guy next to me, tearing up his mutuel tickets. Horse won a million-dollar race and all itll get is a bag of carrots.

Onscreen, the commentators gnaw through the gristle of the bet-busting finale while the winning horse idles on the toffee-coloured Kentucky dirt track, calm and unimpressed, as his rider inhales the boozy grandstand cheers. The horse I bet $10 to win, Dunkirk, stumbled out of the gate. And Papa Clem, the seven-horse I bet to show (i.e., finish in the top three) was edged out for bronze at the wire. In real life, I dont part with money this easily. I take out movies from the library and purchase toner-refill kits for my printer on eBay; I buy the coffee thats on sale, not the kind I really like. Gambling, then, is self-betrayallike being an Amish astronaut.

Hateful notions spin-cycle within my skull. I curse out the horses as million-dollar pigs, pedigreed abominations. I curse out the jockeys as pampered, albeit skilfully waxed, tree monkeys. And then I curse out the over-biting, rheumy-eyed oldsters around me whove won moneymy useful, young-man moneytoday, wishing eight oclock dinners and kidney stones on them all. No wonder this sport is dying, made irrelevant to todays gambler by looser gaming restrictions and more expedient methods of wagering: online poker, Internet sports betting, virtual backgammon, video slots, and, of course, casinos within walking distance. A half-hour passes between races at any track; living in this hurry-hurry world, people cant lose their money fast enough.

Of course, my sense of being financially violated is compounded by the fact that Im here to see my own horse, which I bought with my own money, race for the very first time with me as her owner. What seemed enticing as a wouldnt-it-be-nice scheme now feels disorienting and costly.

I join the bettors outside on the apron, the paved area between the track and the grandstand. Like its aging clientele, Hastings is not without charm, but is far from its most dapper, dewiest prime. Beyond the newly installed slot machines, the racecourse, built in 1889, wears its recent paint job like a threadbare but freshly pressed suit. Behind the grandstand youll find the outdated hockey rink and the charmingly creaky amusement park, which sits quietly until the summer, when the annual fair, the Pacific National Exhibition, lets city kids pet farm animals and eat deep-fried Oreos. Beyond the tracks dirt oval, the immense, eggplant-purple mountains squat on their haunches behind the Cascadia Terminal and the ships in the port. Its a tycoon-pricey view in a predominantly working-class neighbourhood; if the city were drawn from scratch today, the track wouldnt be allowed these sightlines.

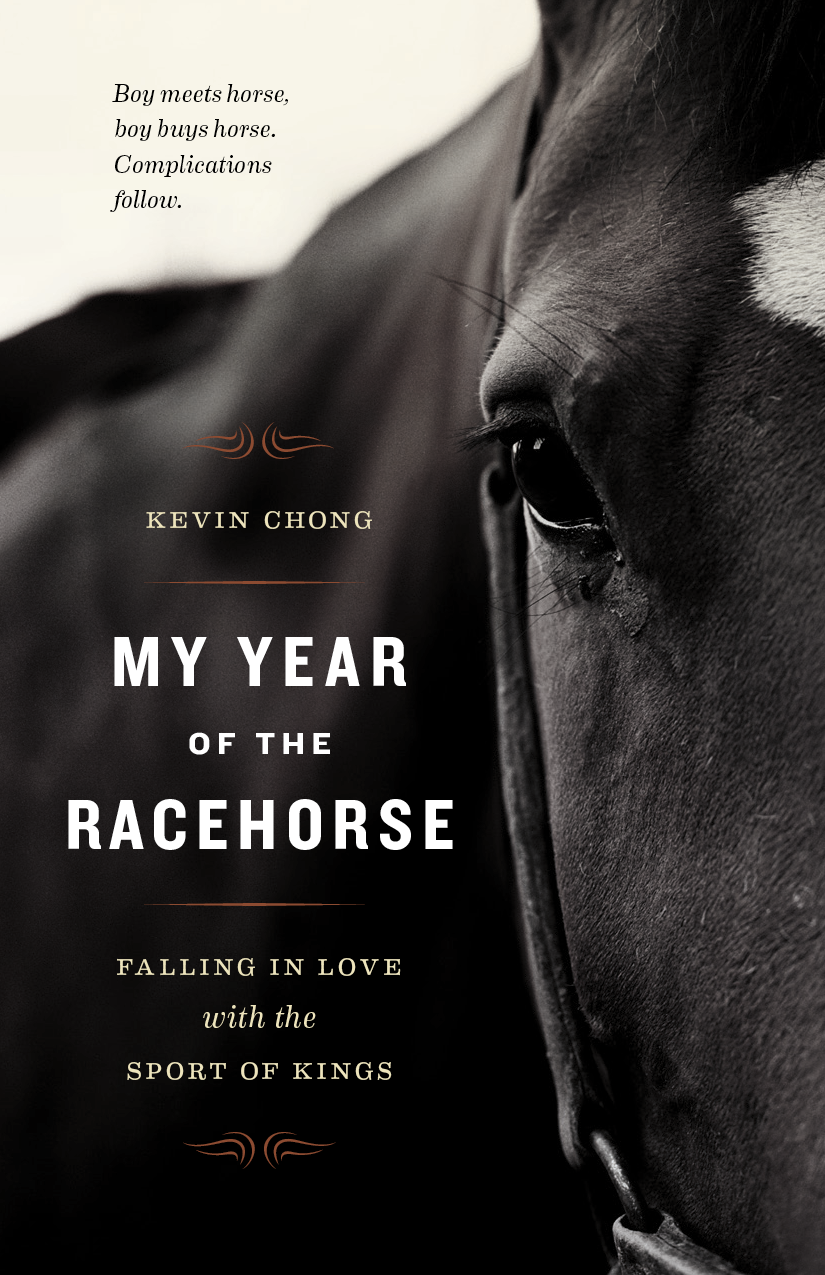

A pre-recorded fanfare trills over the PA. The four-legged land yachts float down the front stretch in single file. One of these horses, my horse, is a five-year-old, bay-coloured mare with a white star between her eyes. Her official name is Mocha Time, but she has been nicknamed Blackie by her trainer, Randi.

Later, I will learn that Mocha Time likes bananas; that she has the equine personality of a biker chick; that she was considered promising, then, before she was rehabilitated by Randi, deemed a glue-factory candidate; that she earns her keep as a bottom claimer, the lowest rung of racehorse, by substituting raw exertion for ability; that she makes cheques despite an ungainly gallop. But, when I see her then, shes just another horse.