Table of Contents

FOREWORD

By Douglas Brinkley

In the late 1970s, when I was in junior high school, my mother gave me a copy of John Steinbecks Travels with Charley, a memoir about his journey across America by camper with only his French poodle as companion. The book resonated with me. Every summer our family left Perrysburg, Ohio, in a station wagon pulling a twenty-four-foot Coachman trailer in Steinbeck-like fashion. For six weeks, we visited national parks and literary landmarks while traveling down interstates and blue highways alike. These road trips galvanized my interest in America more than any textbook possibly could have. So my mother quite naturally thought that I would enjoy Travels with Charley, and I did.

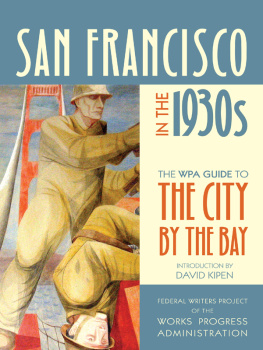

An unintended consequence of my first reading of Steinbecks 1962 book was that I started to collect WPA guidebooks as a hobby. Early in Travels with Charley, Steinbeck raved about the aesthetic excellence of the WPA guides compiled during the Great Depression. He called them the most comprehensive account of the United States ever written. Steinbeck had jammed his suitcase with the American Guides (as they were first known), and he insisted that they were worth their weight in gold. Intrigued by his promotion of these bygone relics, I soon asked my local librarian in Perrysburg to let me study the guidebooks up close. Before long, I was reading about the Oklahoma hills and the Florida flats, Chicagos Miracle Mile and Pittsburghs great steel mills, the Great Smokies and Crater Lake. And the sections of photographs were simply tremendous.

From that moment, I was hooked. As a college student at Ohio State University, I used to scan the shelves of used bookstores and collected the WPA guidebooks as if they were stamps or coins. To date, I own 197 of the volumes, most of them with dust jackets (albeit torn). Everyone who becomes enamored with these volumes has his or her own favorite; mine is the WPA Guide to Illinois. William Least Heat-Moon said he couldnt have written PrairyErth (a deep map) (1991) without the Nebraska guide. When John Gunther hit the road for his memoir Inside U.S.A. (1947), his suitcase bulged with WPA guides, too. Anybody who takes the time to read a WPA guide (and not merely flip through one) comes away with an understanding that its regional, social, and economic histories were written, in many cases, by stellar prose craftspeople. With no disrespect to the transcendentalists, its fair to say that the WPA guides were composed by the most dazzling group of writers America has ever produced.

Now, at long last in Soul of a People, David A. Taylor tells the behind-the-scenes stories of the WPA guides and much more. After rummaging through private and public archives and interviewing WPA veterans, Taylor has written a lively, informative, and often uplifting story of the Federal Writers Project. Created in 1935 in the heart of the Great Depression era, the Writers Project (part of the Works Progress Administration) at its peak supported more than seventy-five hundred writers, editors, and researchers and received four years of federal financing. When the government funds expired, Congress let the program continue under state sponsorship until 1943. Although people were grateful for even subsistence wages in a time of economic despair, few participants deemed it a badge of honor to earn $20 to $25 a week from the government. But their embarrassment at being on emergency relief work has been our great gain. Many of these young writers went on to create enduring works of American fiction, nonfiction, and oral history.

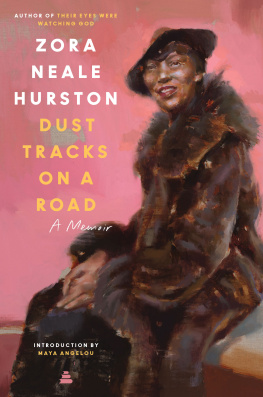

Taylor takes a different view from most New Deal scholars. For the first time ever, the multiculturalism of the Federal Writers Project is explored. As youll find in these pages, the Projects directors believed that the United States could (and should) build a national culture based on diversity. Facing a huge challenge from reactionaries like Martin Dies of Texas, the Ku Klux Klan in several states, and anti-immigration laws that were regularly passed in Washington, D.C., the WPA writers nevertheless forged ahead. They celebrated an astonishing range of often marginalized Americans: Florida turpentine workers, California grape pickers, Nebraska hoboes, and Louisiana folk artists. A roll call of the writers who worked on the WPA guides is a veritable Whos Who of our finest talent: Conrad Aiken, Nelson Algren, Saul Bellow, Arna Bontemps, Edward Dahlberg, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Kenneth Patchen, Philip Rahv, Kenneth Rexroth, Harold Rosenburg, Studs Terkel, Margaret Walker, Richard Wright, and Frank Yerby.

Reading Soul of a People made me want to hit the used bookstores for some of the volumes Im missing. The Nevada and Maine state guides, in particular, I desperately covet. As for the city guides, I crave Lexington and the Bluegrass Country and Atlanta: The Capital of the South. Theyll both soon be mine. Put another way, Im ready for a road trip, and instead of Charley serving as copilot Ill bring along this wonderful new history by David A. Taylor.

Let the travels begin!

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Soul of a People has been a great collaborative effort. I would particularly like to thank Studs Terkel and Stetson Kennedy for their wisdom and generosity. Ann Banks, Christine Bold, Peggy Bulger, Jerrold Hirsch, and Bernard Weisberger showed the way as researchers and historians and provided the documentary team with important insights and guidance. The book and the documentary also owe a debt to the work of Jerre Mangione, Dennis McDaniel, Pamela Bordelon, and William Leuchtenburg.

My thanks to Douglas Brinkley for his enthusiasm for this topic. Louie Attebery, David Bradley, Michael Chabon, Jack Dies, Dena Polacheck Epstein, Dagoberto Gilb, Maryemma Graham, Herb Lewis, Sharon Maust, Gordon McLester, Mindy Morgan, Leo Seltzer, Ruthe Sheffey, and Susan Swetnam answered rounds of questions with good humor. Many more named in the text gave generously of their time and expertise, including the wonderful Grace Paley.

Andrea Kalin has been a supreme partner in making Soul of a People, with her ability to see the path, sharpen the storytelling, and inspire others. Olive Emma Bucklins work on the documentary script uncovered valuable new insights. James Mirabello has been an irreplaceable stalwart on this effort for as long as the Writers Project itself lasted and has earned special thanks for his patience and his dedicated research, professionalism, and production support. He also took a leading role in the photographic research, along with Bonnie Rowan, Lewanne Jones, Alicia Melton, Oliver Lukacs, Eitan Charnoff, and Zachary Ment. Other members on the Spark Media team who contributed their time and talents include David Grossbach, Nancy Camp, Dennis Boni, Lenny Schmitz, Luis Portillo, Wanakhavi Wahisi, Debra Jackson, Maribel Quezada, Danielle Metz, and Joseph Vitarelli.

Valuable support for the documentary came from Steve Rabin, John Y. Cole at the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress, Sandra Parks, Al Stein, and the Smithsonian Institution, particularly David Royle, Chris Hoelzl, and Addie Moray.

I am grateful for support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, particularly Tom Phelps, NEH director of Public Programs; David Weinstein, our program officer; and Sonia Feigenbaum, vice president for the Office of Public Programs. The NEH provided grants for the research, scriptwriting, and production of the documentary. Additional funding came from the Illinois Humanities Council; the Nebraska Humanities Council; the Maryland Humanities Council; the Wisconsin Humanities Council; Humanities Texas; and the Idaho Humanities Council. We also have enjoyed warm support from the American Library Association and the Library of Congress.