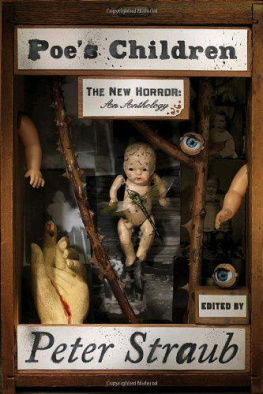

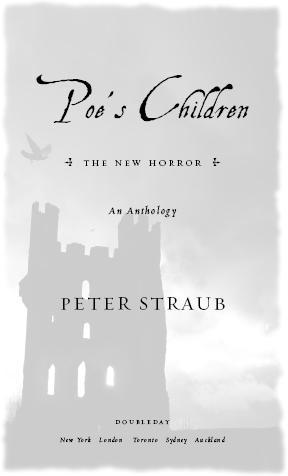

Peter Straub - Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology

Here you can read online Peter Straub - Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology : summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology " wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology " online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CONTENTS

Introduction

I could say: Kelly Link created a world, and it then had been there all along. Or: John Crowley entertained the possibility of a grand possibility, and after that it had always been in place, available for use. Something similar could be said of all the superb writers in this book, which category includes every one of its contributors, from Dan Chaon to Rosalind Palermo Stevenson. Each of these writers either came through to the recognition, or were permitted by a generous environment early on to understand, that the materials of genrespecifically the paired genres of horror and the fantasticin no way require the constrictions of formulaic treatment, and in fact naturally extend and evolve into the methods and concerns of its wider context, general literature. Yet most professional reviewers of fiction instinctively tend to protect the categories that simplify their tasks. Therefore, when faced with work that, while indisputably though perhaps even in some not-quite-definable sense connected to a genre like sf or horror, also possesses literary merit, they tend to fall back on the convenient old shell game of expressing their admiration by saying that the work in question transcends its genre.

Now, let us be clear about this. Claiming that a work transcends its genre is almost exactly like saying, as people once were wont to do, that an accomplished African-American gentleman, someone say like John Conyers or Denzel Washington, is a credit to his racethe unstated assumption of course being that the race in question needs all the help it can get. (One day Id like to hear an after-banquet introducer describe some silver-haired New England WASP as a credit to his race.)

By my own ground rules, then, I have been called a credit to my race maybe half a dozen times, directly or indirectly, and about half of those times I was dumb enough to feel flattered. These days, publishers market a product they are happy to call literary horror, but when I first appeared everyone understood that horror was inherently trashy, unliterary to the core, actually rather shameful, literatures wretched slum. Teenaged boys and other degenerates were its natural demographic. Of course Poe had somehow crept into the canon, maybe because Baudelaires translations had fooled the French into mistaking him for a reputable figure; hints and echoes of the supernatural filled Hawthornes books; Henry James had written The Turn of the Screw and The Jolly Corner and other great ghost or horror stories; and Edith Wharton had written many wonderful ghost stories. These figures, so important to me that in my 1979 novel Ghost Story I had not only named two principal characters James and Hawthorne but inserted into its first part what I called a junked-up version of The Turn of the Screw, were nonetheless safely in the past. During the late seventies, when you thought of horror, you did not think of the Master of Lamb House, Rye. What came to mind instead were paperbacks with graphics of broken dolls, severed heads, or minimalist mouths letting slip single drops of blood.

(When at a lovely, crowded party in London in 1977 I complained about the dripping severed head on the newly released paperback of my latest book, its publisher told me, Peter, that book isnt for people like you. Too stunned to reply, I turned around and aimed for the bar.)

Really because of the marketing approach reflected in those gaudy paperback covers, which included packing the newly popular category with far too many titles by authors whose ambitions went no further than that market, horror as a category overflowed its banks during the late eighties and flooded the chain-stores shelves with malevolent orphans, haunted brownstones and haunted farms and haunted subway cars, ancient curses, things in bandages, evil toddlers, zombies at play, Nazi vampires underwater lesbian Nazi vampire turtles, my now-deceased friend Michael Mc-Dowell joked while impaneled at a genre convention in Rhode Island. In the early nineties, in a Guest of Honor speech at a World Horror Convention in New York, I responded to the decaying world I saw around me by saying that horror was a house that horror had already moved out of.

The statement earned me some hostile glances during the evenings celebrations, for far too many younger writers present had trusted that their extravaganzas about back-country zombies or teenaged vampires were one day going to settle them on or near the best-seller lists, in the vicinity of their favorite books by V. C. Andrews, Ann Rice, Stephen King, Dean Koontz, and a few others. It never happened. None of these twenty-and thirtysomethings who had plotted Regicide and Koontzicide while the well-padded target at the podium dispensed urbane twaddle about Emerson and All Things Glittering and Gleaming (or whatever it was; he was having an Emersonian moment) into the microphone ever got near any best-seller list, and over the next decade a lot of them faded from view.

Which helped prove my point of view. The process has nothing to do with best-seller lists, but time has a tendency generally to support the proposition that very good work survives, while work that is not very good does not. Who now reads, to pick three of the best of the pack, Ken Eulo, Robert Marasco, or Frank deFelita, all of whom once had great success with books that now seem more than a bit, well, gestural?

What I had not anticipated, though, was that over the next ten to fifteen years there would appear a number of writers of fantasy, science fiction, and horroramong them, Kelly Link, M. Rickert, Graham Joyce, Elizabeth Handwho had far more in common with one another and perpetual wild cards like John Crowley and Jonathan Carroll than they did with those writers who were supposed to epitomize their fields. They were literary writers and genre writers at the same time. When Bradford Morrow invited me to guest-edit Conjunctions 39: The New Wave Fabulists (2002), I accepted on the spot, thinking that his much-respected, smart, and intrepid journal would provide the perfect showcase for these writers, most or all of whom would be unknown to its regular subscribers. The benefits of such an encounter should, I thought, flow both ways. And so, as far as I can determine, it proved: the issue was widely reviewed, much praised, and it went into three or four printings. It also inspired a couple of other anthologies edited by people who understood exactly what we were trying to do.

Poes Children very much continues on from The New Wave Fabulists, and this time I am free to include work by breathtaking literary writers, who in this newly liberated atmosphere have no problem embracing their inner Poe, or to put it another way, no problem making use of the strengths and insights made available to them from their own personal engagements with horror and sf. (For reasons having to do with length, along with many other people I wanted to include, Michael Chabon and Jonathan Lethem are not represented in this volume, but they fall into the same category.) This crossover is entirely welcome, I think, as it erases boundaries and blurs distinctions that sometimes seem designed mostly to keep everyone in their proper place.

In November 2003, when Stephen King was awarded the National Book Awards Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, he went out of his way to invite the resplendent audience before him to read the latest fiction by a number of his writer friends. He went on to praise the books. Not long afterward, the distinguished novelist who had just won the NBA for Best Novel, and whom until that moment I had admired, included in her acceptance speech the remark that she did not think those present needed to be given a reading list. At that moment, Stephen King and I had the same thought: youre wrong, lady, you could really use that reading list.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology »

Look at similar books to Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology . We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Poes Children: The New Horror: An Anthology and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.