Shadowland

By

Peter Straub

"If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you."

More than twenty years ago, an underrated Arizona schoolboy named Tom Flanagan was asked by another boy to spend the Christmas vacation with him at the house of his uncle. Tom Flanagan's father was dying of cancer, though no one at the school knew of this, and the uncle's house was far away, such a distance that return would have been difficult. Tom refused. At the end of the year his friend repeated the invitation, and this time Tom Flanagan accepted. His father had been dead three months; following that, there had been a tragedy at the school; and just now moving from the well of his grief, Tom felt restless, bored, unhappy: ready for newness and surprise. He had one other reason for accepting, and though it seemed foolish, it was urgent - he thought he had to protect his friend. That seemed the most important task in his life.

When I first began to hear this story, Tom Flanagan was working in a nightclub on Sunset Strip in Los Angeles, and he was still underrated. The Zanzibar was a shabby place suited to the flotsam of show business: it had the atmosphere of a forcing-ground for failure. It was terrible to see Tom Flanagan here, but the surroundings did not even begin to reach him. Either that, or he had been marked by rooms like the Zanzibar so long ago and so often that by now he scarcely noticed their shabbiness. In any case, Tom was working there only two weeks. He was just pausing between moves, as he had been doing ever since our days at school - pausing and then moving on, pausing and moving again.

Even in the daylit tawdriness of the Zanzibar, Tom looked much as he had for the past seven or eight years, when his reddish-blond curling hair had begun to recede. Despite his profession, there was little theatricality or staginess about him. He never had a professional name. The sign outside the Zanzibar said only 'Tom Flanagan Nightly.' He used a robe only during the warming - up, flapdoodling portion of his act, and then twirled it off almost eagerly when he got down to serious business - you could see in the hitch of his shoulders that he was happy to be rid of it. After the shedding of the robe, he was dressed either in a tuxedo or more or less as he was in the Zanzibar, waiting patiently to have a beer with a friend. A misty Harris tweed jacket; necktie drooping below the open collar button of a Brooks Brothers shirt; gray trousers which had been pressed by being stretched out seam to seam beneath a mattress. I know he washed his handkerchiefs in the sink and dried them by flattening them onto the tiles. In the morning he could peel them off like big white leaves, give them a shake, and fold one into his pocket.

'Ah, old pal,', he said, standing up, and the light reflected from the mirror behind the bar silvered the extra inches of skin above his forehead. I saw that he was still trim and muscular-looking, in spite of the permanent weariness which had etched the lines a little more deeply around his eyes. He held out a hand, and I felt as I shook it the thickness of scar tissue on his palm, which was always a rough surprise, encountered on a hand so smooth. 'Glad you called me,' he said.

'I heard you were in town. It's nice to see you again.'

'One gratifying thing about meeting you,' he said. 'You never ask 'How's tricks?'

He was the best magician I ever saw.

'With you, I don't have to ask,' I said.

'Oh, I keep my hand in,' he said, and pulled a pack of cards from his pocket. 'Do you feel like trying again?'

'Give me one more chance,' I said.

He shuffled the cards one-handed, then two-handed, cut them into three piles, and then reassembled the pack in a different order. 'Okay?'

'Okay,' I said, and he pushed the cards toward me

I picked up two-thirds of the pack and turned the card now on top. It was the jack of clubs.

'Put it back.' Tom sipped at his beer, not looking.

I slid the card into a different place in the deck.

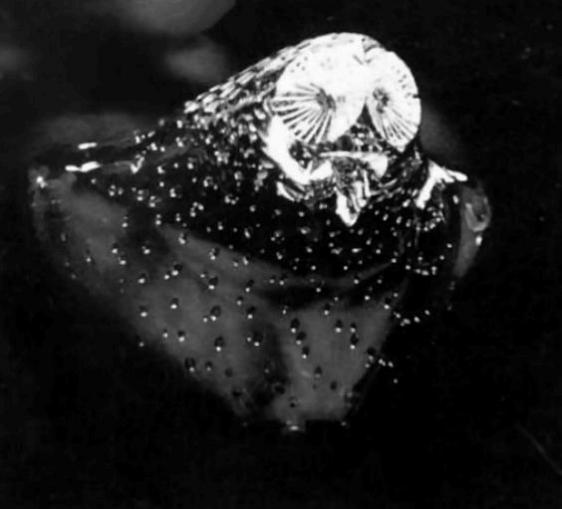

'Better watch closely.' Tom smiled at me. 'This is where the old hocus-pocus comes in.' He tapped the top of the deck hard enough to make a thudding noise. 'It's coming up. I can feel it.' He tapped again and winked at me. Then he lifted the top card off the deck and turned it to me without bothering to look at it himself.

'I can't figure out how you do that,' I said. If he had wanted to, he could have pulled it out of my pocket, his pocket, or from a sealed box in a locked briefcase: it was more effective when done simply.

'If you didn't see it then, you never will. Stick to writing novels.'

'But you couldn't have palmed it. You never even touched it.'

'It's a good trick. But no good on stage - not much good in a club. They can't get close enough. Paying customers think card tricks are dull anyhow.' Tom looked out over the rows of empty tables and then up at the stage, as if measuring the distance between them, and while he pondered the uselessness of skills it took a decade to perfect, I measured another distance: that between the present man and the boy he had been. No one who had known him then, when his red-blond head seemed to shoot off sparks and his whole young body communicated the vibrancy of the personality it encased, could have predicted Tom Flanagan's future.

Of course those of our teachers still alive thought of him as a baffling failure, and so did most of our classmates. Flanagan was not our most tragic failure, that was Marcus Reilly, who had shot himself in his car while we were all in our early thirties; but he might easily have been the most puzzling. Others had taken wrong directions and failed so gently that you could still hear the sigh; one, a bank officer named Tom Pinfold, had gone down with a crash when auditors found hundreds of thousands of depositors' dollars missing from their accounts; only Tom Flanagan had seemed to turn his back deliberately and uncaringly on success.

Almost as if Tom could read my mind, he asked me if I had seen anyone from the school lately, and we talked for a moment about Hogan and Fielding and Sherman, friends of the present day and the passionate, witty fellow-sufferers of twenty years past. Then Tom asked me what I was working on.

'Well, actually,' I said, 'I was going to start a book about that summer you and Del spent together.'

Tom leaned back and looked at me with wholly feigned shock.

'Don't try that,' I warned. 'Nearly every time I've seen you the past five or six years, you've gone out of your way to tease me with that story. You asked enigmatic questions, dropped little hints - you wanted me to write about it.'

He smiled briefly, dazzlingly, and for a second was his boyhood self, pumping out energy. 'Okay. I thought it might be something you could use.''

'Just that?' I challenged him. 'Just something I could use?'

'After all this time you must realize that it's more or less in your line. And I've been thinking lately that it's about time I talked about it.'

'Well, I'm happy to listen,' I said.

'Good,' he said, seemingly satisfied. 'Have you thought about how you want to start it?'

'The book? With the house, I thought. Shadowland.'

He considered that for a moment, his chin still propped on his hand.

'No. You'll get there eventually anyhow. Start with an anecdote. Start with the king of the cats.' He thought about it a moment more and nodded, seeing it as a problem in structure, like his act. I had seen him improve it in a dozed ways, revising with a craftsman's zeal, always bending it more truly toward the last illusion, which should have made him famous. 'Yes. The king of the cats. And maybe you should really start it at the school - the story proper, I mean. If you look back there, you should find some interesting things.'

Next page