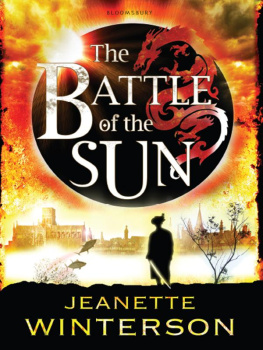

The

BATTLE

of the

SUN

Also by Jeanette Winterson

Tanglewreck

The

BATTLE

of the

SUN

JEANETTE

WINTERSON

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, Berlin and New York

First published in Great Britain in November 2009 Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

36 Soho Square, London, W1D 3QY

This electronic edition published in December 2009 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright Jeanette Winterson 2009

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978-1-40880-891-7

www.bloomsbury.com

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books.

You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

To my godchildren,

Eleanor and Cara Shearer,

who made this happen,

and to myself, a long time ago.

Woof!

CONTENTS

On the fourteenth of August 1601, the Keeper of the Tides

dropped his net into the River Thames,

and pulled out a golden fish.

I t began as all important things begin by chance.

It was about twelve oclock midday. The Thames was busy with boats of every kind; oarboats, sailboats, whelk boats, wherries, tideboats, oyster boats, barges, boats scooped out simple as a saucer flat and shallow and so small that a cat could ride in one by himself. Great boats gilded, decked, cushioned, studded, crimsoned, velveted, proud, pennants and flags flying. Dragboats towing trees for timber, fishing boats, where a boy leant against the mast, arms waving, out over the waves and slop of the tidal river.

The water-craft came from every side, and down the middle too, so that there was no upriver and downriver, only a stream of boats, a race of boats, hugger-mugger, dodging one another, grazing one another, sometimes so close that a man putting a sausage to his mouth found he had fed the lady at the oars in the whelk boat next to him.

The sun was on the river so that everything seemed brighter and more lit up that day. Even the severed heads of the traitors, pitched on their tall spikes at Temple Bar, had the look of pompom bushes waiting to come into leaf. Jack thought he saw one of the heads look straight at him, but it must have been the sun in his eyes.

Jack. He heard the clock strike midday. To tell the truth Jack was chiming twelve himself, like the clock at midday. It was his birthday and he was twelve years old on the fourteenth of August. He counted the clock, nine, ten, eleven, twelve. Twelve years old in the Year of Our Lord 1601.

Jack ran, pushing and zigging and zagging through the sellers and hawkers on the riverbank. He was tall for his age, and his mother had apprenticed him early to a printer and bookbinder. He would live with half a dozen other boys, and serve his master for seven years. But all that would start tomorrow, and first he was going to be given a spaniel for his birthday. He knew the spaniel, he had seen the spaniel, he had named the spaniel. Max. Max Max Max! The best of a litter of four pups, and Jacks very own dog.

Jacks mind that day was all spaniel, there was nothing in it but spaniel. There were no thoughts of food or drink or school or a ball blown out of a pigs bladder and kicked halfway across London with his friends. Inside Jacks head was a night-sky-black dog with stars that were his eyes, and ears soft as sleep. Jack was so almost a spaniel himself that day that he nearly ran four-legged the faster to get home.

Home was the big house that sat between the Strand and the River Thames. It was known to everyone as The Level, though no one seemed to know why, and it belonged to Sir Roger Rover, a man with green eyes and a red beard, who some said was a pirate, but if he was a pirate he was a very good pirate, for the Queen herself was fond of him, and often sent him off to sea on her private business.

In this house, Jacks mother Anne lived as housekeeper, and Jack did jobs around the stable-yard, fetching water, polishing tack, sweeping the courtyards for the many visitors who clattered through the great arch off the Strand.

It was a fine house, a fair house, whose gardens let on to the river itself, and it was to the water-gate, and through those gardens, that Jack was coming home, when... When... it happened.

Two men, short, hooded, black boots, black cloaks, black hats, were waiting either side of the water-gate. As Jack came through, panting from his run, the men seized his body, pinioned his arms, threw a rough damp torn sack over him and bundled him into a waiting boat.

Be this the one?

This be the one, sure as I have a tongue and one ear.

His accomplice laughed. If he be not the one, you shall have a tongue or one ear but never both on the same head.

Quiet, you water-rat! Give him the drink.

The man held back Jacks head and opened his mouth with his fingers, as you would to a dog, then the other fellow poured a thick red liquid down Jacks throat. Jack spat and coughed and choked, but he had to swallow some of it. It tasted bitter. It was gritty. It was like fire ashes or fine-ground oyster shells mixed up in red vinegar.

The men shoved Jack into a closed coop at the stern of the boat. It was a poultry boat and there was a big slatted wooden hen-coop perched at one end where the fowls were rowed to market. Jack looked out through the torn sack and the slats of the boat; the boat was being rowed rapidly east. Jack wanted to shout out, but he couldnt because he was dizzy, and the last thing he saw were the boats on the river no longer going up and down, but round and round and round and round like at a fair.

Jack felt a great dullness, like the world spinning to a stop at the end of time. He passed into a dead and dreamless sleep, a black place.

The men in the boat sat still without speaking. One lit a clay pipe.

As the boat reached its mooring place, several servants dressed in grey came to meet it. Jack was carried from the coop, and the boat and the two men rowed on, distant now, towards Limehouse.

The servants took Jack down and down and down. They laid him there and walked away. There was nothing more to do.

At home, his small spaniel could not be quieted, and ran up and down, down and up, stopping and crying in a dark corner of the room. Jacks mother, standing at the water-gate, had a sense, an instinct, that her son was alive but in danger.

He is a boy, hes fallen over, hes eating apples, hes met with a friend, said the groom, wondering why women never used good commonsense but fretted and worried over simple foolish things.

He was to be here at twelve midday, said Jacks mother, and if he comes not to be here by twelve at midnight, then shall I go to him.

And how shall that be done? said the groom, laughing at her, in all the teeming city of London, its lanes, lodgings, highways and byways, inns and dens, how shall you, a woman, find one strayed boy?

Next page