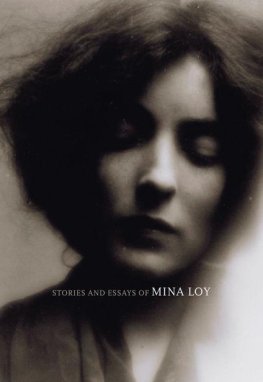

Her hands are white and long and lithe. They make elusive, fleeting framesflirtations of shapes, reallyon anything they touch. Anything in the world. I would follow those hands out to the desert. I would. I would watch them on the black leather curve of the steering wheel. I would watch them light a cigarette with the glowing car lighter after it made a low pop and smelled vaguely of burnt food. And I would watch them as she gestured when she spoke, as if she were weighing air or beckoning someone near. At times I notice her watching her own hands, admiring their white elegant angles and delicately draped bones. When I notice her watching her own hands, I look away, my eyes shy from shame.

Mina, she says, and I like it when she says my name and leaves it there hanging, like a statement, or barks it, Mina, like an order.

Leave everything, she says. The one thing you cant leave behind is the thing you absolutely must.

OK, OK, sure, but we take money. Lots and lots of it. Lorenes more than mine. And her car. But nothing else. Not a book or a change of clothes. Not a ring or a stocking or a journal or a fountain pen.

We lunch at a truck stop. Laminated menus with heart-healthy options. Pale coffee and everything smells like syrup.

Look, sugar cubes, Lorene says, dropping one after the other into her coffee, letting each one balance on the spoon, then submerging it until it becomes saturated with the pale brown liquid.

It reminds me of a commercial, I say.

Yeah, Lorene says, me too. Why do I keep doing this, she submerges the cube slowly and watches it absorb coffee, why do I get such a kick out of this.

I dont remember which, maybe not sugar, I say. Maybe the cube is used as a demonstration.

You mean an absorbency demonstration? Lorene asks.

Yes, exactly something almost like that. Absorbency.

There were so many demonstration commercials. So visual, so scientific.

Sugar cubes. I really like sugar cubes. Whyd they go and get rid of sugar cubes? I say, all of a sudden extremely sad about it.

Packets, perhaps, offer labels, small type, nutritional information, a higher ability to sanitize. Last longer. Theres the anticipatory shaking gesture, loading the granules into one end of the envelope so it can be torn without spilling. Improved delivery system of loose granules versus cubes. Dissolves easier. Makes it easier to use more. Nefarious plot to destroy my bodys ecosystem. Yeast- and microbe-feeding, inner-organ-caramelizing sugar, Lorene continues, stirring her coffee, pushing it back and taking another drag on her cigarette. But it makes the coffee palatable, which in turn makes the cigarette enjoyable, which in fact makes the morning bearable.

The waitress is adjusting her stockings. She thinks no one is looking, and she pulls at the fabric of her skirt, nearly jumps with the pull. She reaches to the back of her knee, gets a handful of nylon, inches it up, a minor hike, then tries again, through the skirt, the little jump-hike.

A perfect system. Airtight. No complaints, I say.

Still, I know that isnt it. No good reason to get rid of cubes. An object of unremarked-upon delight rendered less than what it was. Its what Michael would say, its the sort of pleasing detail you never seem to notice until one day its gone.

Lorene slips two fingers through the handle of her coffee cup and braces it against the fingertips of her other hand. She lifts the cup to her mouth, closes her eyes, and sips the hot, sugary liquid.

But maybe, just maybe, thats not it either. Maybe sugar cubes seem pleasing just because theyre gone, and that kind of detail brings you pleasure only as a contemplated lost thing, the pleasing nature of it is realized only because of its absence.

One Month Before Leaving:

The Cocktail Hour

Mina watched him, examining his profile at twenty paces. Mina watched him, half-shadowed, through a window, half-lit with the amazing dusk light, even, or especially, L.A. movie-fake dusk light that could be thrown by a switch in a sound-stage. A fading soft pink light that made her long for soundtrack swells, the softness making her think she longed for every person she ever thought she should have loved a little more, but really it was only a scented-hanky kind of nostalgia, an antiques shop nostalgia, or, finally, a cable channel documentary-type nostalgia for people and places you never even knew, not a longing for home, but a longing for home. Mina had a weakness for this kind of bungalow dusk melodrama. When the whole city caught her off guard she found an emotional attachment to its past and she read its ugliness as its charm. It was then she felt she had finally got it, that it was her place, fleetingly, if only because of the light and its fading glow.

He was part of that light, and she could not stop watching him in it. Through their window. From a distance. Not just that, but his unawareness of her watching.

For the past two hours she had done the unthinkable, the violate: she walked. First through the Vista Del Mar neighborhood of old tiny 1920s bungalows, sort of Spanish Colonial with odd Moorish and Eastern flourishes, stuccoed and surrounded by palm trees, so arranged and moderne they seemed carved in Bakelite. Car-free, in summer ballet flats, the only one besides gardeners and children, Mina walked along curbs and looked through interior-lit windows, the fading dusk light affording anonymity, the TVs and stereos and nearly audible conversations providing a schizoid soundtrackstrange juxtapositions of familiar radio sounds with other peoples lives at an audio glance. Sometimes just a name, spoken and unanswered, hung in the air, or whole arguments at high volume. She could pause and listen for hours to fragments of conversations about dinner or car keys or mail.

She had walked the long way from Maxs apartment in the Hills, then headed down Gower past Sunset and Santa Monica. The streets had already thickened with homebound cars, five oclock sliding into six oclock, a special segue time that was once called, by someone, somewhere, the cocktail hour. People used to slip seamlessly from Hollywood General on Highland, from all the rattan and wickered bungalows on the Paramount lot over on Gower, to, where? Maybe the Cinegrill at the Roosevelt Hotel. To a padded banquette at the Dresden, around crescent-shaped tables seemingly designed for fourth-wall-theater staging, or an In a Lonely Place lonely stool at the bar at the Brown Derby, or Musso and Franks. Or a dozen other bars, long gone, that used to line Gower and Hollywood. Gowers Gulch. Actors, extrascowboys and gladiators. And all those suit-spectacled execs, in her mind all as young and three-buttoned and black-and-white as the photo of Irving Thalberg her father used to have in his study. It had that name, Gowers Gulch, back when it had a history, used to be called Gowers Gulch when cowboy-actor extras hung out, waiting in between calls at Paramount and Hollywood General. Minas father told her (and where did he learn it, because it was well before his time, this ancient Hollywood history he seemed to know a priori and with detailed authority) theyd still be in costume, bursting into bars as if they were Wild West saloons, Max Factord pink plastic cowboys getting drunk, starting fights, feeling the difference between real bottles and breakaway glass. Mina walked past the corner minimall with its Western-style burnt-wood hanging sign. Gowers Gulch Convenience Center. Nice touch, and she wished, particularly when she passed the huge wrought-iron and adobe gates of the studio, that one teensy cowboy-actor bar had been salvaged, a secret perfect dive where she could have a drink that would afford her sanctuary, someplace simple and unself-conscious, a modest, sad dilapidated spot, an establishment offering mere refreshment and a minute of quiet solitary enjoymenta real drink, away from the ubiquitous new and bright and sandblasted. A bar, her father would have said, where there is no shame in ordering a scotch. Where a person could smoke a cigarette unmolested. But there were none, and Mina instead wandered into the old Paramount studio store, where in a montage of lightning editscolor, hand, pocket, money, color, exitshe quickly bought an armful of expensive cosmetics. A teal eye powder. A tiny brush to apply it. A waxy-smelling lipstick in a blue red (Caput Mortuum) made for black-and-white photography. Translucent face powder, loose, of course, and the fluffy real-horsehair brush to apply it. A bottle of Red nail polish. A concealer stick, in Bisque #9, Medium Fair. She left quickly, buzzing with the secrets of the universe in her paper bag, followed by, within seconds, dire regret. She opened the bag, there on the sidewalk, out in the sunlight, and stared at the Red nail polish, all wrong, really, the polishactually a Midwestern near-red, sort of weathered-barn colorednot what she wanted at all. She stood there, dismayed by her failure to even address the shelf of red nail polishesthe Original Real Red polish, so close to Raven Red and Scarlet Red but darker, oddly, than Carmine Crimson Redhow she avoided the issue altogether, just grabbing Red, not even Simple Red, and of course the polish would never be exchanged, but tossed in a drawer with thirty other nearly perfect unused colors, until it became old and its chemical components started to separate, all the colors finally turning into an umber-orangey rusty red topped with a pool of murky colorless oil. She would just have to wait until she could devote the time, until she felt up to determining which, finally, would be Rita Hayworth Red. She barely resisted the urge to toss the whole bag of cosmetic purchases and go back in, to do it right, microexamine the red polishes, head back in there and trial-and-error the whole row. Spend hours on it. But instead she ambled in a zigzag on the pavement, staggering vaguely away from the place, her head looking back while her body went forward, nearly stumbling into a young woman approaching her, unexpected and unnoticed, seemingly curb-sprung, touching her arm (touching her!) on the sidewalk.