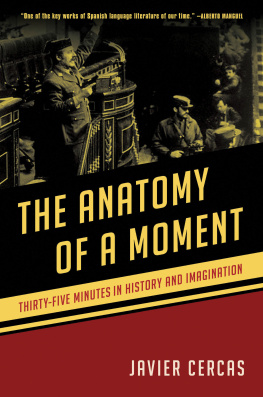

THE ANATOMY OF A MOMENT

Javier Cercas

Translated from the Spanish by Anne McLean

In memory of Jos Cercas

For Ral Cercas and Merc Mas

he who made... the great refusal

Dante, Inferno , III, 60

Contents

PART ONE

PART TWO

PART THREE

PART FOUR

PART FIVE

PROLOGUE

In the middle of March 2008 , I read that according to a published in the United Kingdom almost a quarter of Britons thought Winston Churchill was a fictional character. At that time I had just finished a draft of a novel about the February 1981 coup dtat in Spain, and was full of doubts about what Id written and I remember wondering how many Spaniards must think Adolfo Surez was a fictional character, that General Gutirrez Mellado was a fictional character, that Santiago Carrillo or Lieutenant Colonel Tejero were fictional characters. It still strikes me as a relevant question. Its true that Winston Churchill died more than forty years ago, that General Gutirrez Mellado died less than fifteen years ago and as I write Adolfo Surez, Santiago Carrillo and Lieutenant Colonel Tejero are still alive, but its also true that Churchill is a top-ranking historical figure and, if Surez might share that position, at least in Spain, General Gutirrez Mellado and Santiago Carrillo, not to mention Lieutenant Colonel Tejero, do not; furthermore, in Churchills time television was not yet the main fabricator of reality as well as the main fabricator of unreality on the planet, while one of the characteristics that defines the February coup is that it was recorded by television cameras and broadcast all over the world. In fact, who knows whether by now Lieutenant Colonel Tejero might not be a television character to many people; perhaps even Adolfo Surez, General Gutirrez Mellado and Santiago Carrillo might also be to a certain extent, but not to the extent that he is: apart from people dressing up as him on comedy programmes and advertisements, the lieutenant colonels public life is confined to those few seconds repeated each year on television in which, wearing his tricorne and brandishing his new standard-issue pistol, he bursts into the Cortes and humiliates the deputies assembled there at gunpoint. Although we know he is a real character, he is an unreal character; although we know it is a real image, it is an unreal image: a scene from a clich-ridden Spanish film fresh from the hackneyed brain of a mediocre imitator of Luis Garca Berlanga. No real person becomes fictitious by appearing on television, not even by being a television personality more than anything else, but television probably contaminates everything it touches with unreality, and the nature of an historic event alters in some way when it is broadcast on television, because television distorts (if not trivializes and demeans) the way we perceive things. The February coup coexists with this anomaly: as far as I know, its the only coup in history filmed for television, and the fact that it was filmed is at once its guarantee of reality and its guarantee of unreality; added to the repeated astonishment the images produce, to the historic magnitude of the event and to the still troubling areas of real or assumed shadows, these circumstances might explain the unprecedented mishmash of fictions in the form of baseless theories, fanciful ideas, embellished speculations and invented memories that surround them.

Heres a tiny example of the latter; tiny but not banal, because it is directly related to the coups televisual life. No Spaniard whod reached the age of reason by February 1981 has forgotten his or her whereabouts that evening, and many people blessed with good memories remember in detail what time it was, where they were, with whom having watched Lieutenant Colonel Tejero and his Civil Guards enter the Cortes live on television, to the point that theyd be willing to swear by what they hold most sacred that it is a real memory. It is not: although the coup was broadcast live on radio, the television images were shown only after the liberation of the parliamentary hostages, shortly after . on the th, and were seen live only by a handful of Televisin Espaola journalists and technicians, whose cameras were filming the interrupted parliamentary session and who circulated those images through the in-house network in the hope theyd be edited and broadcast on the evening news summaries and the nightly newscast. Thats what happened, but we all resist having our memories removed, for theyre our handle on our identity, and some put what they remember before what happened, so they carry on remembering that they watched the coup dtat live. It is, I suppose, a neurotic reaction, though logical, especially considering the February coup, in which it is often difficult to distinguish the real from the fictitious. After all there are reasons to interpret the February coup as the fruit of a collective neurosis. Or of collective paranoia. Or, more precisely, of a collective novel. In the society of the spectacle it was, in any case, one more spectacle. But that doesnt mean it was a fiction: the February coup existed, and twenty-seven years after that day, when its principal protagonists had perhaps begun to lose for many their status as historical characters and enter the realms of fiction, I had just finished a draft of a novel in which I tried to turn February into fiction. And I was full of doubts.

How could I even dream of writing a fiction about the February coup? How could I dream of writing a novel about a neurosis, about a paranoia, about a collective novel?

There is no novelist who hasnt felt at least once the presumptuous feeling that reality is demanding a novel of him, that hes not the one looking for a novel, but that a novel is looking for him. I had that feeling on February 2006 . Shortly before this date an Italian newspaper had asked me to write an on my memories of the coup dtat. I agreed; I wrote an article in which I said three things: the first was that I had been a hero; the second was that I hadnt been a hero; the third was that no one had been a hero. I had been a hero because that evening, after hearing from my mother that a group of gun-toting Civil Guards had burst into the Cortes during the investiture vote for the new Prime Minister, Id rushed off to the university with my eighteen-year-old imagination seething with revolutionary scenes of a city up in arms, riotous demonstrators opposing the coup and erecting barricades on every corner; I hadnt been a hero because the truth is I hadnt rushed to the university with the intrepid determination to join the defence of democracy against the rebellious military, but with the libidinous determination to find a classmate I had a huge crush on and perhaps take advantage of those romantic hours, or hours that seemed romantic to me, to win her over; no one had been a hero because, when I arrived at the university that evening, I didnt find anyone there except the girl I was looking for and two other students, as meek as they were disoriented: no one at the university where I studied not at mine or any other university made the slightest gesture of opposing the coup; no one in the city where I lived not mine or any other city took to the streets to confront the rebellious Army officers: except for a handful of people who showed themselves ready to risk their necks to defend democracy, the whole country stayed at home and waited for the coup to fail. Or to triumph.

Thats a synopsis of what I said in my article and, undoubtedly because writing it reactivated forgotten memories, that February I followed with more interest than usual the articles, reports and interviews with which the media commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the coup. I was left perplexed: I had described the February coup as a total failure of democracy, but the majority of those articles, reports and interviews described it as a total triumph of democracy. And not just them. That same day the Cortes approved a says that every destiny, however long and complicated, essentially boils down to a single moment the moment a man knows, once and for all, who he is. Seeing Adolfo Surez on that February sitting still while the bullets whizzed around him in the deserted chamber, I wondered whether in that moment Surez had known once and for all who he was and what significance that remote image held, supposing it did hold some meaning. This double question did not leave me over the days that followed, and to try to answer it or rather: to try to express it precisely I decided to write a novel.

Next page