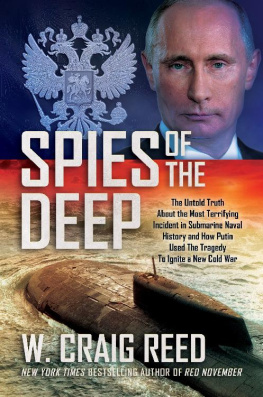

When I first proposed this story to a magazine editor in mid-August 2000, the event was only a day old and the world was riveted by the televised images of a rescue in progress. There were reports of trapped sailors knocking from inside a sunken submarine in a shallow area of the Barents Sea, and experts agreed they could be brought out alive. Though the Russians had mysteriously rebuffed foreign-rescue offers, some of those foreigners leaped into action anyway. I was optimistic.

Id envisioned something like the feel-good story of the long-shot Apollo 13 rescue, only better: saving the Kursk submariners would go down in history as an international bonding experience. Lingering East-West tensions would fade as former enemies joined in a common purpose, pooling the best resources and bravest rescuers to bring those boys out alive. In my eighteen-year career, Id chronicled more than my share of tragedy. This would be different.

Instead I watched with growing dismay as the Russian government threw a befuddling series of obstacles into the paths of foreign rescuers, and the reports of the submariners tapping disappeared.

The difficulty in unraveling this new riddle of why Russia had seemingly sabotaged a rescue of its own men now loomed like an enormous Rubiks Cube. My stock-in-trade was to untangle complicated stories until I could present the truth. Its difficult enough with happy outcomes, but now Id be asking impolite questions of notoriously tight-lipped officialsin a country Id never been to, in a language Id never spoken, in a mysterious and complex world of undersea espionage and warfare that Id always found deeply baffling.

One of my first phone calls was to the Russian embassy in Washington, D.C., where Id hoped to start getting the proper clearances to work in this former evil empire. What makes you think I can help you with this? asked Yuri Zubarev, the embassys press attach.

Well, what, indeed? As an unaffiliated, independent journalist, I was looking at a yearlong process just to get accredited to report from within Russia. And accreditation was only the first in a series of escalating hurdles. I opted for a business visawhich would afford me no access whatsoever to official press facilities and eventsand finally set foot on Russian soil in late October, some seventy-five days after the wreck. But the country was still in a state of shock, with official allegations that an American spy sub rammed the Kursk just reaching a shrill crescendo.

At the end of my first week I was wandering around the streets of St. Petersburg in a cold rain, gamely employing my twelve-word vocabulary in a vain attempt to find the apartment of a helpful American expat with translator connections. After an hour or so in the steady downpour, I reluctantly called him on my cell phone. But standing at a five-way intersection where all the signs were written in an alien alphabet, I still could not match his careful instructions; he had to head out into the rain himself to come rescue me. It seemed everything about this project was going to be very hard work.

The ensuing years demanded that every success be hard-won: five reporting trips to Russia; many hundreds of interviews; countless ran-sackings through online Russian media archives; carefully arranged discussions with on-scene military officials; generous technical advisers and dedicated translators every step of the wayfor three and a half years. And this was only for the Russian side of the story.

This narrative account is more than 90 percent factual. The remainder is informed scenario, mostly involving events experienced by the men whose lives were lost. In an effort to craft these sequences responsibly, I have tried to reconstruct them with the help of forensic findings, recovered tapes of onboard dialogues, notes found on submariners bodies, ships logs, Russian naval protocol, family interviews, the firsthand testimony of key participants, and intensive professional guidance.

Most of the three-hundred-plus subjects Ive interviewed for this book agreed to stay on the record. Though their contributions are not attributed within the narrative, I have compiled a liberal accounting in a separate appendix at the books end.

Some general explanations on sources: While I have sifted many thousands of documents about this tragedyincluding countless news reports and narrative treatments and other original documents that have never been publicizedI have tried wherever possible to get close to the subjects themselves for firsthand interviews. Perhaps the most consistently maddening aspect of this story was that the truth always appeared to be a moving target, one in which even those closely involved routinely resorted to speculation about what had happened around them. The facts persistently refused to sit still. For this reason, I repeatedly interviewed as many subjects for key scenes as possible, occasionally subjecting some poor souls to multiple rounds of questioning.

Reconstructed dialogues among living persons come from my own interviews with the subjects involved, or occasionally from published interviews conducted by other journalists. Very infrequentlyand only in exchanges of low consequenceI have resorted to descriptions from intimates who either witnessed the exchanges or received the accounts from participants at a later date.

In some cases that describe a living subjects interior thoughts, many of the rules mentioned above apply. But in some instances, my reconstruction is also based on statements later expressed in interviews that, in my judgment, seemed credibly applied within the moment of dramatic events that form the narrative.

Also in rare cases, I have used firsthand material from subjects who could not allow their names to be published. This includes all dialogues onboard the Kursk and between the Kursk and the Peter the Great, once the sub entered the open sea on its way to the exercise. Those records come from a source close to the Russian investigation.

All weather descriptions come from the records of reporting stations responsible for the times and places described.

Most accounts of actions among key Western actors in the drama are based on my interviews with the subjects themselves, many of whom spoke publicly about the Kursk event for the first time. This includes former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott, who used his own verbatim notes from the first meeting between Presidents Clinton and Putin several weeks after the tragedy to give me an accurate account of that meeting.

For the books formidable technical challenges, I relied most heavily on Lars Hanson, a retired American naval commander and engineer whom Id stumbled upon while aiding National Geographic Televisions own Kursk account in the spring of 2002. Id worked with a number of other technical advisers with limited success, but Larss moxie was of an entirely different order; he rolled up his sleeves and feverishly worked through the Kursk tragedys many mysteries, drawing on a stunning range of high-level skill sets. There were many times when I simply felt like Larss legman, supplying him with key bits of information as he educated me in the world of American and Russian submarines. He certainly could have written this book by himself if hed wanted to.

But for all of his tireless guidance, it must be said that I sometimes chose advice with which Lars disagreed, knowing full well that I did so at my peril. Which is to say I accept full responsibility for any errors in this document.