Also by Tony Booth:

Coxs Navy

Admiralty Salvage in Peace & War

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by

PEN SWORD MARITIME

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright Tony Booth, 2008

ISBN 978-1-84415-589-1

ebook ISBN 978-1-84468-153-2

The right of Tony Booth to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13 Sabon by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire Printed and bound in England by CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

If blood be the price of admiralty,

Lord God, we ha bought it fair!

The Song of the Dead

Rudyard Kipling, 1896

The Admiralty regrets that His Majestys Submarine

Thetis ... has failed to surface

First public announcement,

23.00 hours, 1 June 1939

This book is dedicated to the memory of the

ninety-nine men who perished aboard

His Majestys Submarine Thetis

and to the four who survived

Contents

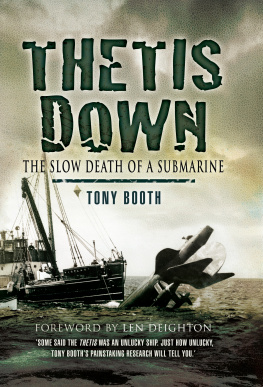

The news that the Royal Navy submarine HMS Thetis had sunk numbed the nation. The shock was made worse by the fact that it was peacetime, and everyone knew that the Royal Navy was the biggest, best and most efficient in the world. It had a dozen battleships and battle cruisers, and five more battleships on the way, and its warships provided a symbol of stability in distant oceans. The Royal Navy did not have accidents, let alone disasters.

Britain was a small and somewhat backward society at that time but it was homogeneous; it shared its jokes and its xenophobia and troubles. Even a street accident could, for a brief time, eliminate social and class differences. The Royal Navy was a microcosm of that Britain. When I say the nation was shocked by this agonizing undersea drama, I mean that it affected just about every man, woman and child. I say this with confidence because I was a child at the time and I remember it vividly. At school the teachers whispered together. As the hours ticked away I would hear people ask What must it be like for those poor sailors? The newspapers published photos showing that the hull of the submarine was visible and high above water. Why dont they just cut a hole in it and get them out? everyone asked. In films we had seen masked bank robbers cutting through steel in minutes; we knew it wasnt too difficult for the Navy.

Tony Booth gives answers to the questions that were posed more than half a century ago. Not that there have not been answers provided before. Books have explained it and films have depicted its heroics. There has been an Admiralty investigation, the conclusions of which were kept secret. There was an official public enquiry (oh, how guilty public officials like official public enquiries). It was concluded that no one was to blame.

Some said the Thetis was an unlucky ship. Just how unlucky, Tony Booths painstaking research will tell you. But just to be getting on with, how about this paragraph from his book? What author of mainstream fiction would dare test his readers credulity with such a Monty Python scene?

When Lieutenant Commander Bolus gave the order to steer to port, the Thetis promptly swung to starboard. Then when he gave the order to steer to starboard she promptly turned to port. By some incredible piece of incompetence the entire steering gear system had been fitted in reverse. Then, when they did attempt to dive, the forward hydroplanes jammed.

Before the Second World War the Royal Navys Submarine Service had been a dumping ground for difficult officers, alcoholics, misfits and those with ideas of their own. The RAFs dumping ground was Fighter Command and the Armys was the Tank Corps. And yet these were the weapons that proved decisive in the coming war.

The journey to the Royal Navys top ranks was made on the bridge of the big battleships where well-spoken, ambitious young officers rubbed shoulders with the gold braid. Britains Admirals loved big battleships, and the Japanese Admirals and United States Admirals were equally love-struck by these obsolete armadillos. Even in the middle of the Second World War the German Admirals remained convinced that the battleship was the decisive weapon and wanted more. All admirals wanted them as Flagships and used them as command posts. In the Pacific, while the oily-handed United States submariners were winning the war almost single-handed, the Admirals were deliberately blocking United States Navy press releases to this effect, in case the cost effectiveness of their precious battleships was questioned.

Although it was the U-boats, and the sophisticated German technology, that made the headlines and almost extinguished Britains seaborne supply lines, the Royal Navys far more primitive submarines contributed greatly to the Allied victory. British submarines sank 169 enemy warships and 493 merchant ships but about one in three of the Royal Navys submarines were lost, one of the highest casualty rates of any service.

As for the sneaky duplicity that the British Admiralty displayed concerning the loss of the Thetis in 1939 we should not judge them too harshly. Their behaviour was not unique. When the United States Navy lost the nuclear submarine USS Scorpion in May 1968 they located it on the seabed within a couple of weeks. But it took another four months before they admitted to finding it and even today the true cause is kept secret. (It was sunk with all hands by a torpedo fired from a Russian submarine.) HMS Thetis and USS Scorpion are two of a long list of submarine disasters that remain shrouded in mystery. The Russian Kursk that sank in the Barents Sea in the summer of 2000 was perhaps the most publicized; the least publicized was the Chinese submarine No. 361 discovered in 2003 by fishermen. It was floating low in the water of the Yellow Sea with its whole crew dead. Who knows what happened? The list goes on, and so do the controversies. The Free French Surcouf was, in February 1942 when it sank, probably the largest submarine in the world. And the determination of the governments concerned to keep the story of its last few hours secret was no less impressive. The cause of its ending is still being argued. Navies have always been a law unto themselves and, since the invention of atomic devices, underwater technology is at the top of the worlds most jealously guarded military secrets.

Warships of any shape or size are self-contained dictatorships. And self-contained dictatorships shroud their troubles in secrecy. It is not surprising that navies such as those of Britain, France, Spain and Russia have in recent times been the focus of mutinies and revolutions.

Next page