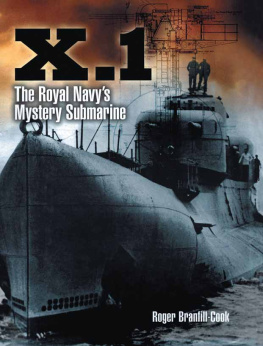

Roger Branfill-Cooks superbly researched book succeeds in shining light on the truth surrounding the capability of X.1 and the military and political conditions that acted as a backdrop to her short career in the Royal Navy.

Submarine cruisers have a great capacity to stir the imagination. The notion that a powerfully-armed vessel can rise to the surface in a deadly ambush, despatch an enemy vessel in a hail of shells, then simply slide away back into the depths has fascinated the submarine designers of Tsarist Russia, Imperial Germany, Great Britain, the USA, France and the Third Reich.

Traditionally, the cruiser type of vessel, successor to the classic sailing frigate, is both the protector and the predator of distant mercantile routes worldwide. A lone frigate or corsair, far from base and support, was always vulnerable to falling in with a faster or more powerful opponent. The Great War gives us the examples of Knigsberg and Emden, and the Second World War was to produce many others including the fatal first and last cruise of the Bismarck. Therefore the cruiser submarine, with her ability to hide from a hunter by simply submerging, seemed to many to be the ideal type of ocean raider. It was no surprise that La Royale should christen their own giant cruiser submarine after the great French corsair captain, Robert Surcouf.

The Royal Navys sole example of a cruiser submarine, the X.1, has long been dismissed as a failure, and a colossal white elephant. She was the only major British warship designed after the First World War which was withdrawn from service before the outbreak of the Second. Her heavy gun armament was her most obvious feature, and this was perhaps her most contentious aspect. It is undeniable she had great potential if correctly used in a surface action role. Paradoxically her very success doomed her to a half-life existence, neither fish nor fowl, spurned both by the exponents of the surface cruiser force, and by the submariners who favoured the more stealthy underwater attack. From the chequered history of her advanced propulsion machinery, it is clear she fell far short of her designers ambitions. However, alternative engines did later become available, which could have been fitted in X.1 to cure her chronic mechanical problems.

Every writer who mentions X.1, however, completely misses the most important aspect of this monster vessel. The resounding success of her design was her docile underwater handling. Designed to prove once and for all that a huge submarine vessel could be dived with safety, X.1 bridges the gap between the clumsy and deadly monster British submarines of the Great War which tended to kill their own crews more readily than those of enemy ships and all the large Royal Navy submarines which followed her, right up to present-day nuclear boats. In retrospect, her greatest failing was that her concept failed to address the political context of the age into which she was launched.

The X in her pennant number stands for experimental, but it also brings an air of mystery, and the story of X.1 is no stranger to mystery and subterfuge. This volume aims to lay to rest once and for all the deliberate, and innocent, misinformation spread about X.1, and tell the true story of the Royal Navys extraordinary secret weapon and her crew.

Left: Sir Arthur W Johns, KCB, CBE (18731937). Sixth Director of Naval Construction, responsible for the majority of Royal Navy submarine classes in the Great War, and the designer of the X.1. Born in 1873 at Torpoint, Cornwall, Arthur William Johns entered Devonport Dockyard as a Shipwright Apprentice at the age of 14. After heading the list of all apprentices in his examination year, he moved to Greenwich Royal Naval College as a probationary Assistant Constructor. In 1895 he qualified with the coveted First Class Professional Certificate. After several minor assignments, he worked on the design of Captain Scotts Antarctic research vessel, the Discovery, as well as the King Edward VII