The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Martha Francis

What is known in civilized countries, what people may be assumed to know, is a great mystery.

Saul Bellow, To Jerusalem and Back

The fat volunteer rolled onto the other straw mattress and went on: Its obvious that one day it will all collapse. It cant last forever. Try to pump glory into a pig and it will burst in the end.

Jaroslav Haek, The Good Soldier vejk

Emperor of Austria

Apostolic King of Hungary

King of Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia, Lodomeria, Illyria

King of Jerusalem, etc.

Archduke of Austria

Grand Duke of Tuscany, Krakw

Duke of Lorraine, Salzburg, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, the Bukovina

Grand Prince of Transylvania

Margrave of Moravia

Duke of Upper & Lower Silesia, Modena, Parma, Piacenza, Guastalla, Auschwitz, Zator, Teschen, Friuli, Ragusa, Zara

Princely Count of Habsburg, Tyrol, Kyburg, Gorizia, Gradisca

Prince of Trent, Brixen

Margrave of Upper & Lower Lusatia, in Istria

Count of Hohenems, Feldkirch, Bregenz, Sonnenberg, etc.

Lord of Trieste, Kotor, the Wendish March

Grand Voivode of the Voivodship of Serbia, etc. etc.

Franz Joseph Is titles after 1867, some of which are more in the nature of brave assertions than indicators of practical ownership

Maps

Introduction

Danubia is a history of the huge swathes of Europe which accumulated in the hands of the Habsburg family. The story runs from the end of the Middle Ages to the end of the First World War, when the Habsburgs empire fell to pieces and they fled.

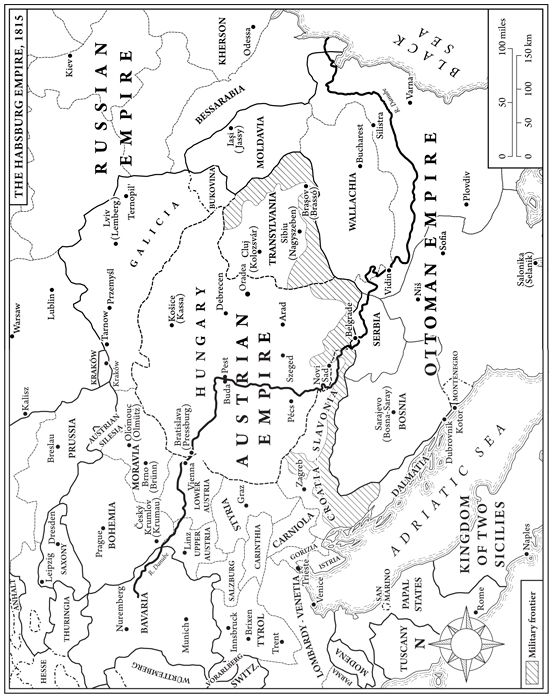

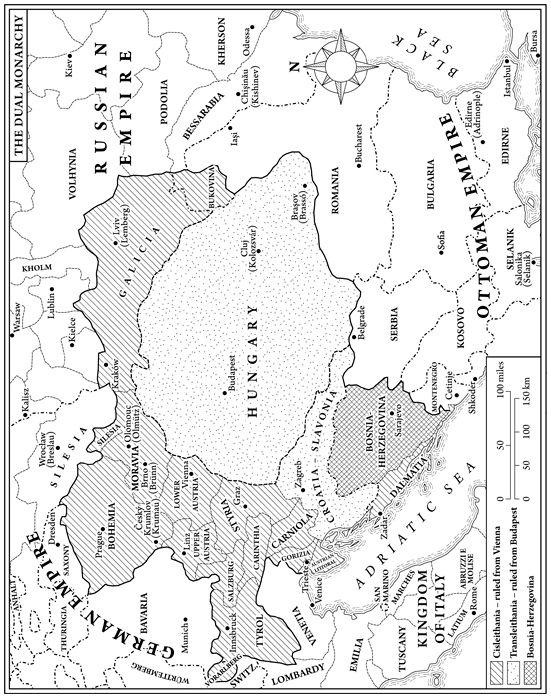

Through cunning, dimness, luck and brilliance the Habsburgs had an extraordinarily long run. All empires are in some measure accidental, but theirs was particularly so, as sexual failure, madness or death in battle tipped a great pile of kingdoms, dukedoms and assorted marches and counties into their laps. They found themselves ruling territories from the North Sea to the Adriatic, from the Carpathians to Peru. They had many bases scattered across Europe, but their heartland was always the Danube, the vast river that runs through modern Upper and Lower Austria, their principal capital at Vienna, then Bratislava, where they were crowned kings of Hungary, and on to Budapest, which became one of their other great capitals.

For more than four centuries there was hardly a twist in Europes history to which they did not contribute. For millions of modern Europeans the language they speak, the religion they practise, the appearance of their city and the boundaries of their country are disturbingly reliant on the squabbles, vagaries and afterthoughts of Habsburgs whose names are now barely remembered. They defended Central Europe against wave upon wave of Ottoman attacks. They intervened decisively against Protestantism. They came to stand against their will as champions of tolerance in a nineteenth-century Europe driven mad by ethnic nationalism. They developed marital or military relations with pretty much every part of Europe they did not already own. From most European states perspective, the family bewilderingly swapped costumes so many times that they could appear as everything from rock-like ally to something approaching the Antichrist. Indeed, the Habsburgs influence has been so multifarious and complex as to be almost beyond moral judgement, running through the entire gamut of human behaviours available.

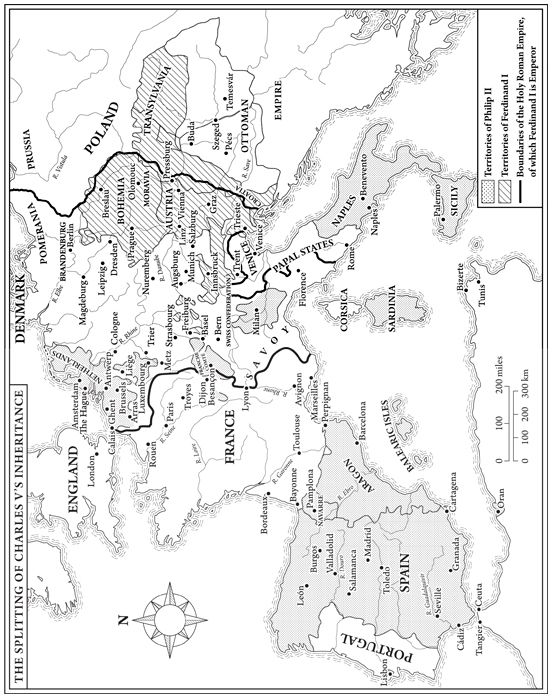

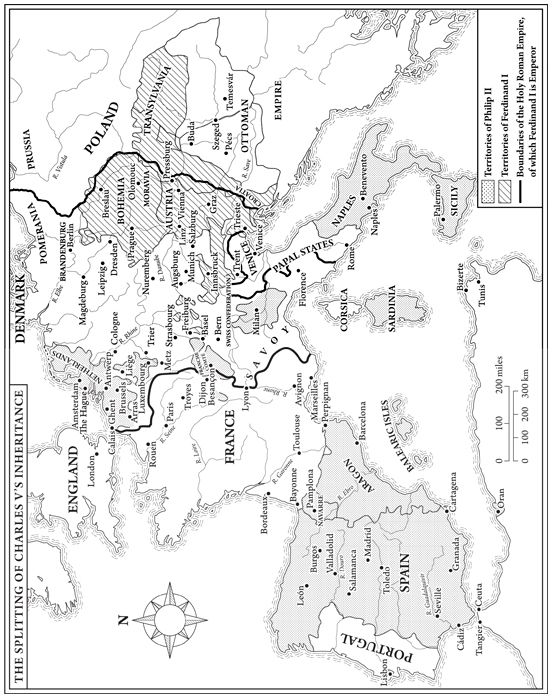

In the first half of the sixteenth century the family seemed to come close as the inheritances heaped up so crazily that designers of coats of arms could hardly keep up to ruling the whole of Europe, suggesting a Chinese future in which the continent would become a single unified state. As it was, the Emperor Charles Vs supremacy collapsed, under assault from innumerable factors, his lands accidental origins swamping him in contradictory needs and demands. In 1555, Charles was obliged much against his will to break up his enormous inheritance, with one half going to his son, Philip, based in his new capital of Madrid, and the other going to his brother, Ferdinand, based in Vienna. At this break-point I follow the story of Ferdinands descendants, although the Madrid relatives continue to intrude now and then until their hideous implosion in 1700.

While writing my last book, Germania , I would sometimes find myself in a sort of trance of anxiety, knowing that it was based on a sleight of hand. With a few self-indulgent exceptions I kept its geographical focus inside the boundaries of the current Federal Republic of Germany. This was necessary for a coherent narrative, but historically ridiculous. Indeed, the structure humiliatingly mocked my main point: that Germany was a very recent creation and only a hacked-out part of the chaos of small and medium feudal states which had covered much of Europe. These hundreds of squabbling jurisdictions existed under the protective framework of the Holy Roman Emperors, who ruled, with admittedly only sputtering success, for a millennium. For the last three hundred and fifty years of the Empires existence, the Emperor was almost always the senior member of the Habsburg family. He had this role because he personally ruled immense tracts of land, indeed at different times owning parts or all of nineteen modern European countries. This meant that he was unique in having a large enough personal financial and military base to be plausible as Emperor. But it also meant that he was often distracted: responsible for great blocks of territory inside the Holy Roman Empire (such as modern Austria and the Czech Republic) but also for unrelated places such as Croatia, say, and Mexico. This distraction, it can be argued, was the key motor for Europes political history.

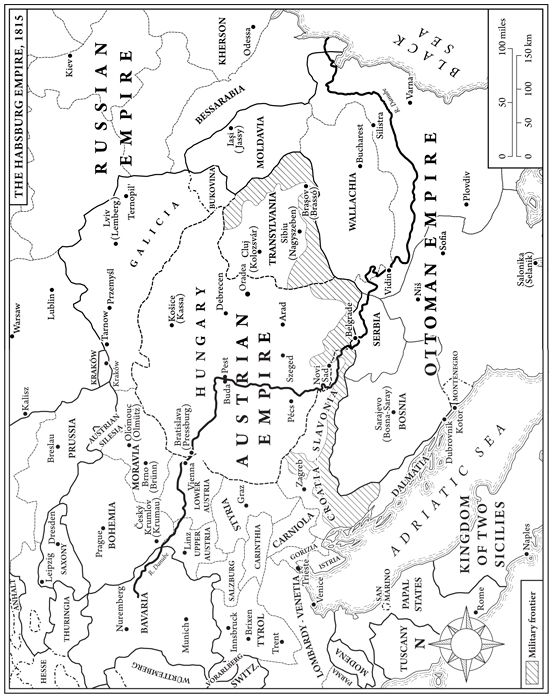

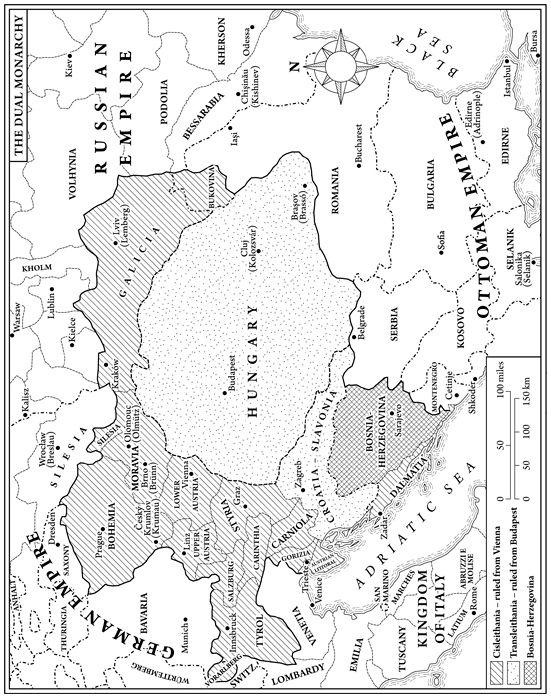

The Habsburg story, of Europes most persistent and powerful dynastic family ruling the world of Germania from bases which were in fact well outside the modern state of Germany, was just too complex to be alluded to except in passing in the earlier book. The Habsburgs influence across Europe was overwhelming, but often the great events of the continents history were generated as much by their uselessness or apparent prostration as by any actual family initiative. Indeed it is quite striking how baffled or inadequate many of the Emperors were, and yet an almost uncountable heap of would-be carnivorous rivals ended up in the dustbin while the Habsburgs just kept plodding along. Through unwarranted luck, short bursts of vigour and events often way outside their control they held on until their defeat by Napoleon. Moving fast, they then cunningly switched the title of Emperor so it referred to what could now be called the Habsburg Empire, meaning just the familys personal holdings, itself still the second largest European state after Russia. They kept going for a further, rather battered century, until final catastrophe as one of the defeated Central Powers in the First World War. The aftershocks from the in many ways accidental end of this accidental empire continue to the present. I allude to some of these in the text, but effectively the narrative ends in 1918 as the different parts of the Empire go their own ways.

Next page