The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

I was in the Ardennes, on a bus travelling from Stavelot to Spa. The bus was filled to bursting with primary- and secondary-school children and I was the only adult, aside from the magnificently stone-faced and imperturbable driver. It was midwinter and the fog was so solid that it looked as though, once outside the bus, you would have to be resigned to washing it out of your hair and brushing strands of it off your coat. The bus was, frankly, a monkey-house on wheels. One child was using a lighter to burn through a plastic handle, another had a phone app which converted a pupils photo into a demon face. At irregular intervals an inflated condom was fired over our heads to happy cries. The whole atmosphere was hilarious and you almost expected the bus to rock from side to side as it drove along, like in an exuberant cartoon. It made me feel wistful about the long-gone years spent waiting for my own children in various school playgrounds. I had forgotten the magical way in which large groups of children flicker in their moods, managing to be morose, thrilled, exhausted and hyper in perhaps less than a second.

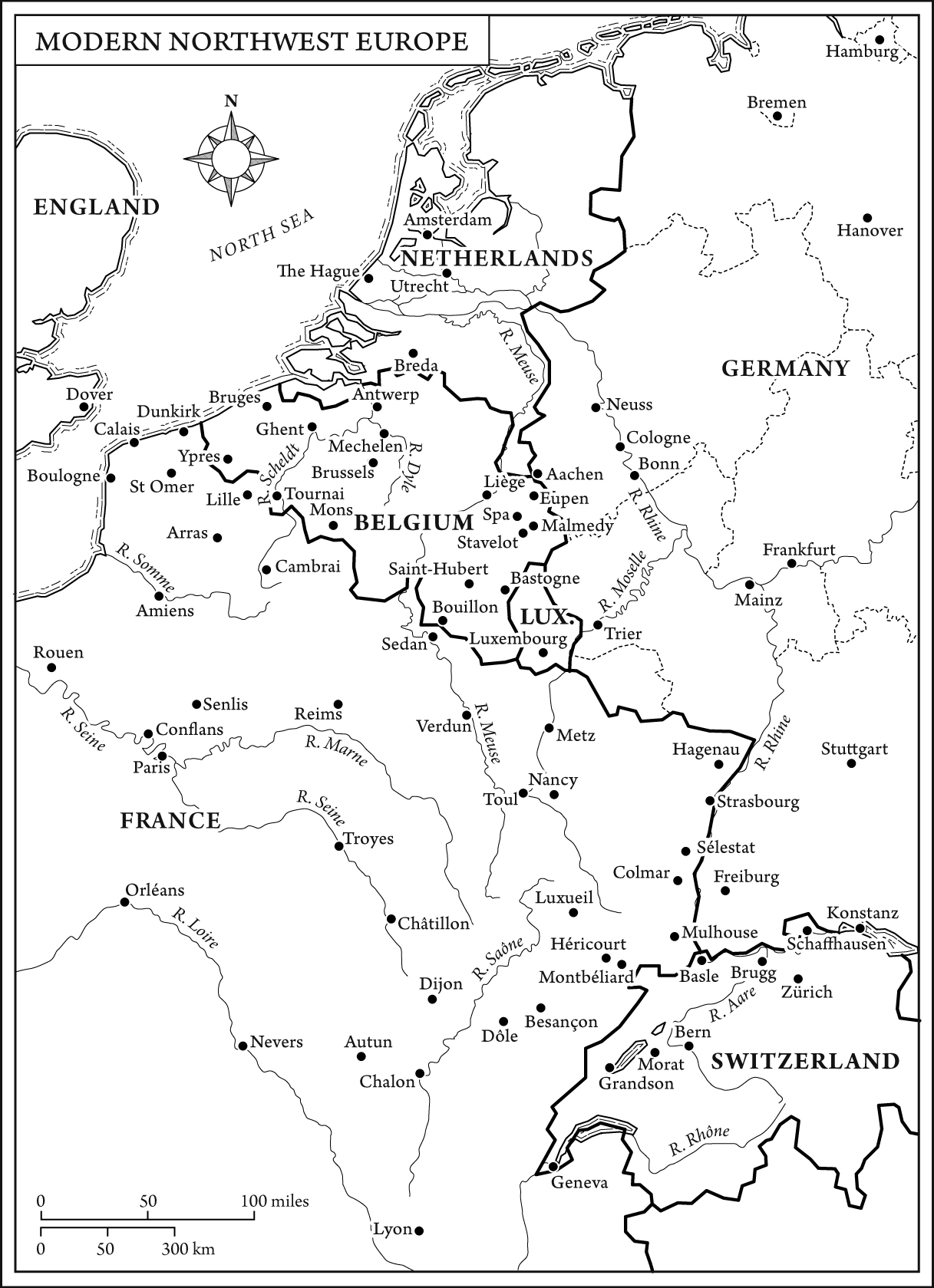

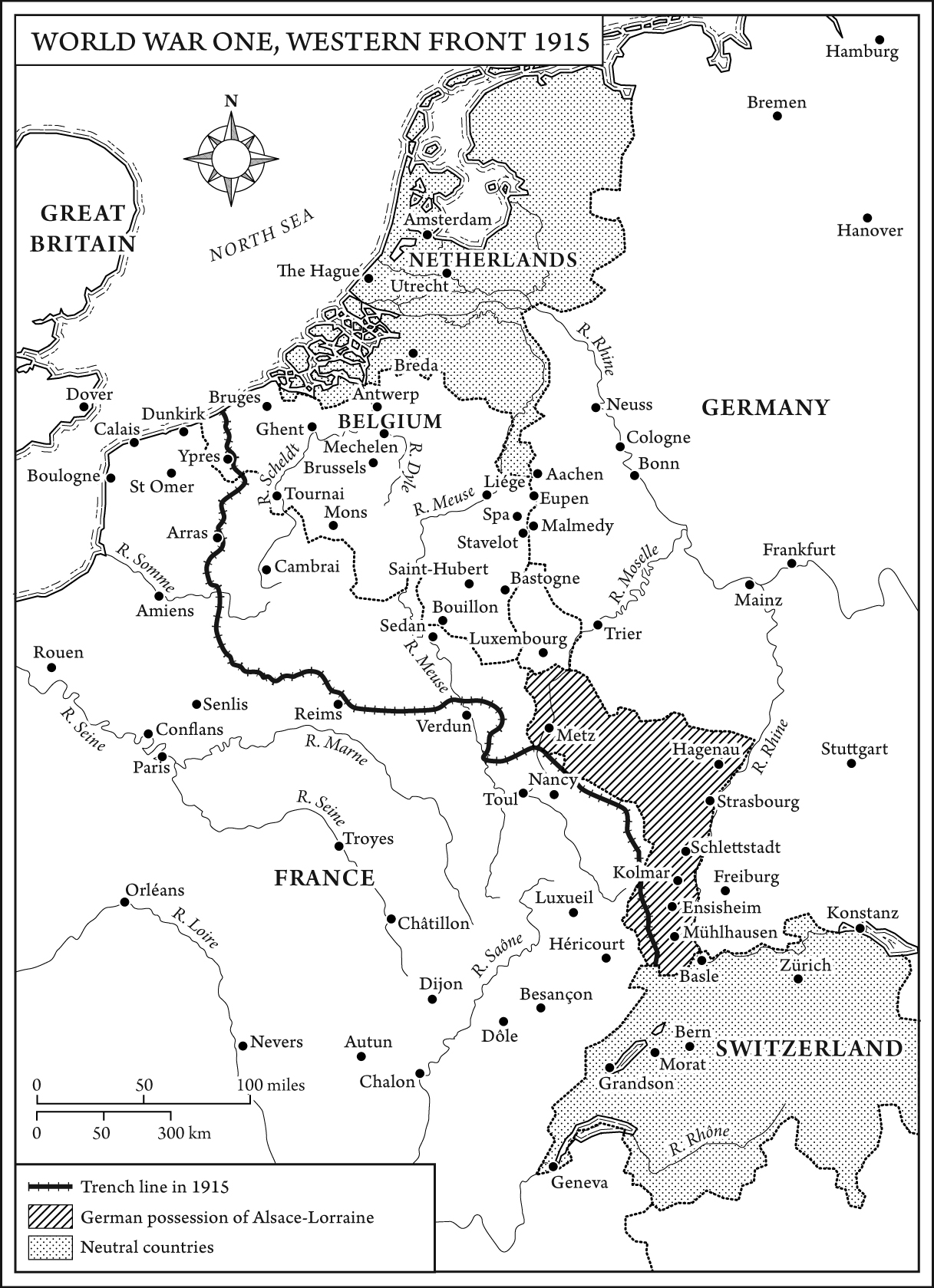

Each stop made by the fog-bound bus was a surprise. As the doors hissed open, a clump of children would gamely launch themselves into what appeared to be a solid form of Milk of Magnesia, with just a roof-angle visible to indicate houses of some kind, and the odd skeletal branch. In all kinds of ways this bus was really in the middle of nowhere a series of rugged, thinly populated valleys which most Europeans have no need to engage with. From the air you would be able to see each valley filled to the brim with fog. But, like so many places I will write about in this book, it has had its turn as the centre of the world. Most obviously this was where the Battle of the Bulge was fought the last major attempt by the Germans to defeat the Western Allies. The little town of Stavelot of which I had previously been entirely ignorant was where the battle reached its high-water mark, in December 1944. American troops had kept destroying bridges and blocking the narrow roads by felling thousands of trees, the Germans kept rigging up pontoons and blowing up the obstacles but at Stavelot they briefly entered the town, massacred dozens of its inhabitants, could not fight their way through, tried to drive round, failed and began the retreat which only stopped with their surrender in May. A small marker in the town states: HERE THE INVADER WAS STOPPED .

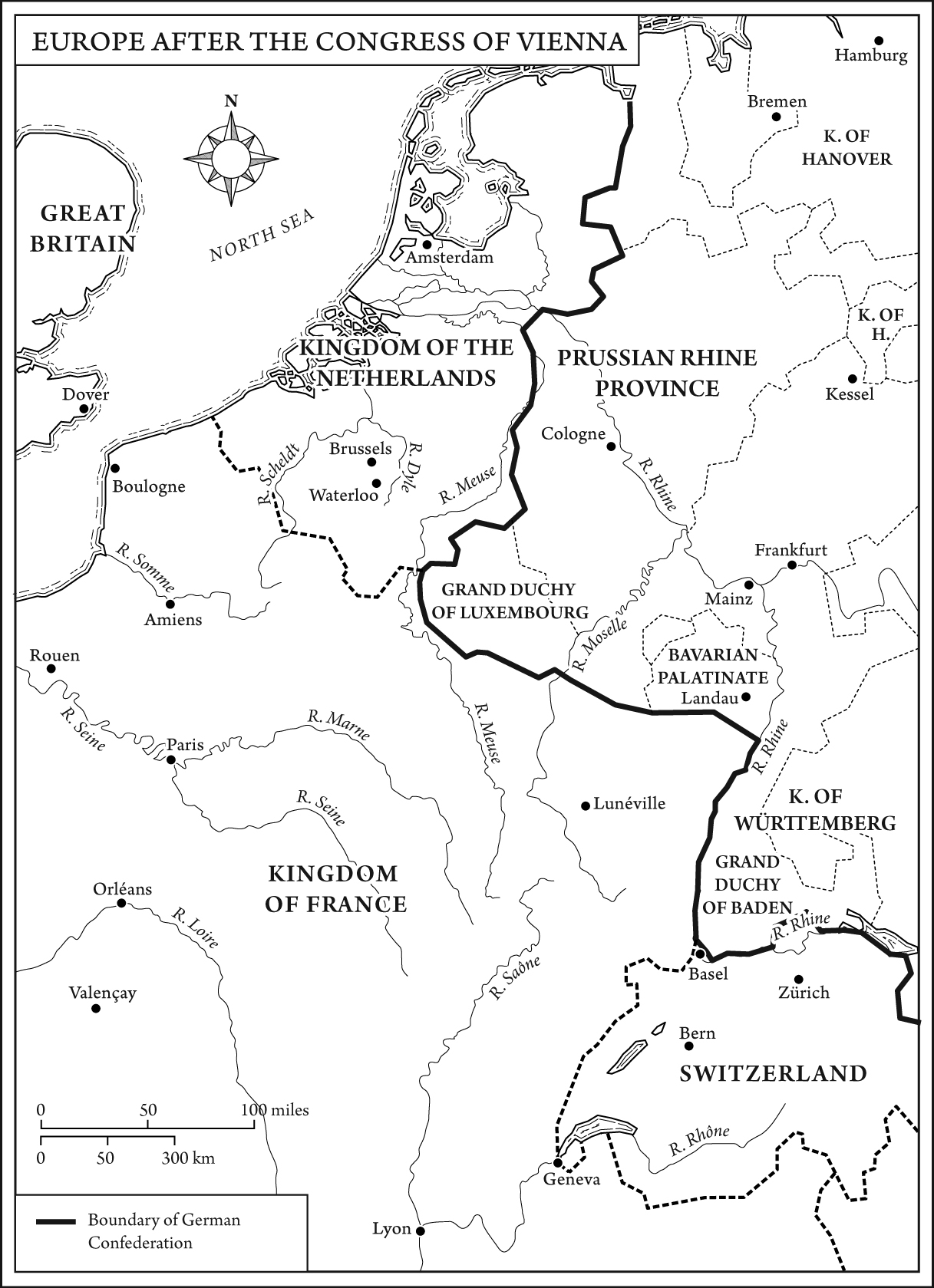

I was surrounded by the same fog that had made the initial German attack through the Ardennes so successful, but this was just one part of the regions central role in the twentieth century. It was, famously, the source of the British and French armies crushing and almost instantaneous defeat in 1940, as thousands of German tanks and troop-lorries secretly wound their way through the same narrow roads. During the First World War, the town of Spa was the German military headquarters in the fightings later period. A series of photos taken in 1918 show the last weeks of imperial and aristocratic rule in Germany, as Kaiser Wilhelm II , the Crown Prince and various generals stand around hobnobbing in their immaculate uniforms in one of Spas commandeered assembly rooms. It was in these rooms that the Kaiser, hearing about the revolution breaking out in Berlin, appealed to his generals for support, only to find that they no longer trusted their men and could not even guarantee that they would not attack him. Wilhelm panicked and fled to Holland, abandoning the imperial train in case troops took potshots at it, and ending over eight centuries of Hohenzollern rule. In 1944 the same complex in Spa was in turn the headquarters of the US Army, evacuated during the temporary panic that followed the surprise, fog-bound German offensive.

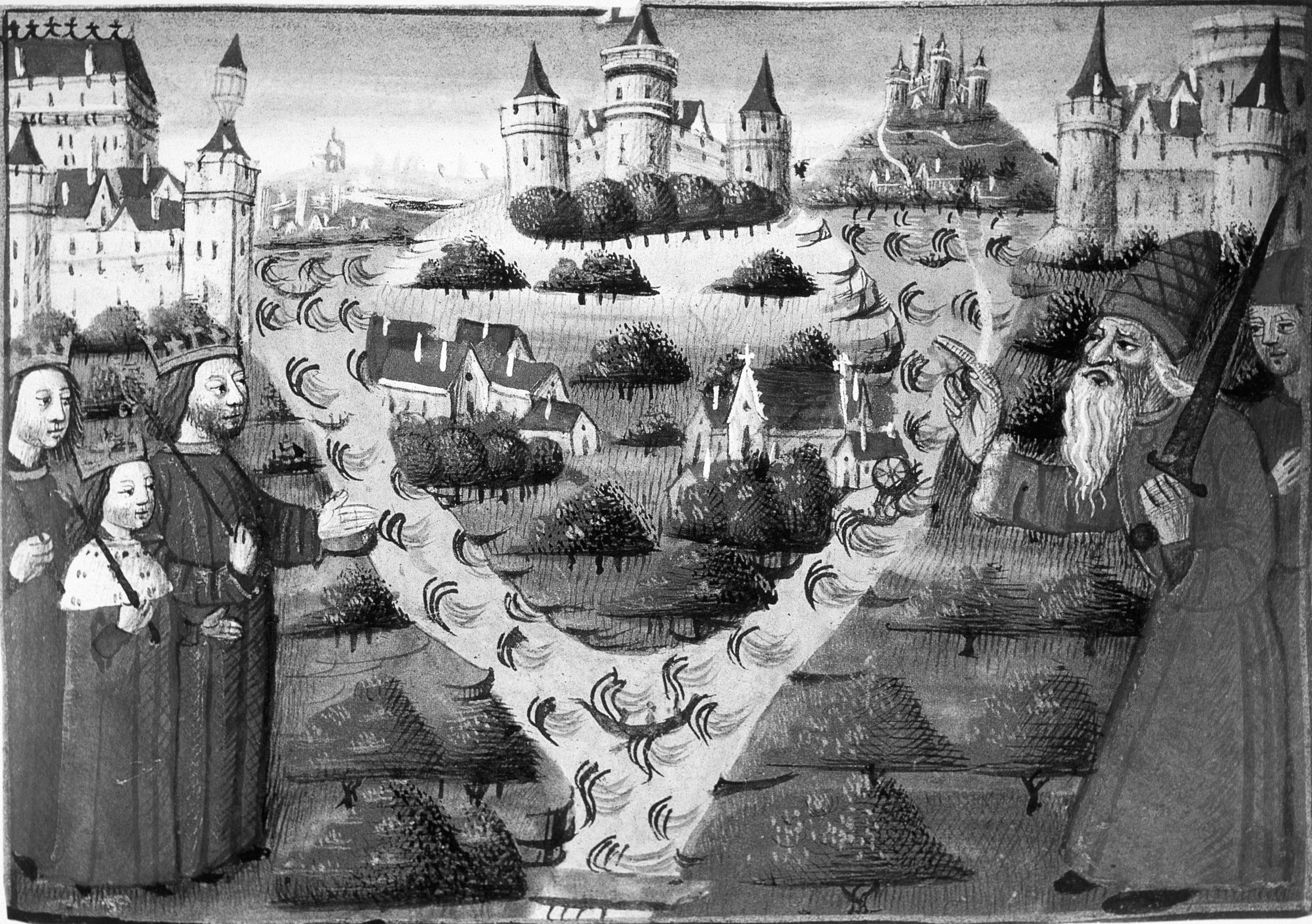

I had come to Stavelot partly out of contrition and annoyance that I had not heard of the place before. It turns out to have a sensational museum in its sprawling former abbey which showed that in the first half of the twelfth century it was the only place to be. But Stavelot once I was there also showed that I really just had to stop my travelling around for this book. There was effectively nolimit to the richness and density of a region that is both the dozy back of beyond, and central to the fate of humanity. Here I was in a bus filled with the great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren of those who had experienced historical events of various, terrible kinds and who were with their jolly backpacks and untiring ability to laugh helplessly when one of their number farted happily oblivious. My own children were now adults and I looked back with dismay at the immense amounts of time I had spent away from them, drifting around dozens of Stavelot-like places, face to face with the same question about why European events and ideas have swept through so many places that just wished to be left alone.

I have always wanted to write these words, but they are now true: this book is the completion of a trilogy! Germania was a history of German-speakers roughly within the modern Federal Republic of Germany. I tried to make it an evenly spread book, but the locations kept being tugged eastwards as I wallowed shamelessly in the tiny towns of Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt. I then wrote Danubia because I was aware that Germania failed to deal with the Germans of Austria or of other points east. Before the twentieth century, German culture had spread into the lands across Central Europe and this opened up several other interests I had, in the nature of competing nationalisms, in the Habsburg family and its many oddnesses, and the ChristianMuslim frontiers that shaped the whole vast region for centuries. As someone who grew up in the Cold War and was, like everyone, gripped by the discovery of what was for a generation a