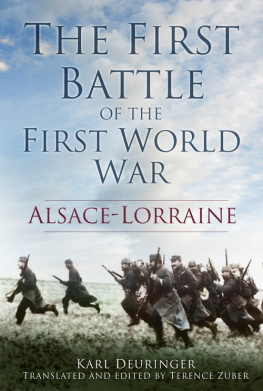

ALSACE AND LORRAINE

FROM CSAR TO KAISER

58 B.C.1871 A.D.

RUTH PUTNAM

Published by Left of Brain Books

Copyright 2021 Left of Brain Books

ISBN 978-1-396-32040-8

eBook Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Left of Brain Books is a division of Left of Brain Onboarding Pty Ltd.

Table of Contents

ALSACE AND LORRAINE

DURING forty-three years these two names have been linked together in a neat phrase. Under that verbal yoke they passed, as the result of the fortunes of war, from one political framework to another. But the two applied to distinct entities. The gradual evolution of each into a semblance of unity out of a congeries of private estates and ecclesiastical foundations, the liege lords they acquired or found imposed upon them, mediate or immediate, the resources, characteristics, customs of each belong to different stories, though sometimes, indeed, containing similar chapters. Alsace and Lorraine were alike in being tiny buffer territories, occasionally little more than geographical expressions, wedged between big interests. Both have suffered as shuttlecocks under blows of battledores from the east and the west. Here are in brief the stories of each.

ALSACE

AS a working basis, the geographical expression ALSACE may be assumed to include a tract bounded by the Vosges Mountains on the west and the Rhine on the east, lying between 47 30 north latitude and 49 15, more or less. The breadth is always Alsatian; the length varies. Its area is about 3350 square miles, making this debated land about equal in size to Lancashire, rather larger than Delaware and smaller than Connecticut. The plain of Alsace, between the mountains and the Rhine, is well watered by the Ill and its tributaries, whence comes the name, ILL-SASS, ELLSASS, Elsass, the seat of the Ill. When the designationa very natural local termwas first applied, is not certain. Nor, indeed, is the derivation of land name from river universally accepted. Several writers, since 1870, have read the phrase Herzge der Elisassen as Dukes of the foreignersElisassen being applied by the Franks to the people in the Vosges region who had crossed from the other side of the Rhine, or by the Germans on the right bank to their fellow-countrymen who had already sought homes on the left. Again, Elsass is read as Edelsass, meaning either the land of the nobles or the noble site.

The earliest form of designation, pagus Alsacinse, found in documents, did not apply to precisely the same tract as the later name. Thus vagueness envelops Alsatian beginnings. But certain events actually happened east of the Vosges Mountains, in the Ill Valley, before it was classed as such, and were described by a Roman eyewitness. With that description this narrative may begin.

I.

Romans, Gauls, and Others on the Soil of Alsace

WHEN Julius Csar was making his way farther and farther into Gaul, he found strained relations between the inhabitants of Gallic race in the vicinity of Mons Vosegusthe Vosges regionand would-be immigrants from over the Rhine. Divitiacus the duan tells the Roman general (De Bello Gallico, i., cap. xxxi.) that about 15,000 Germans had at first crossed the Rhine; but after these wild barbarians had become enamoured of the lands and the refinement and abundance of the Gauls, more were brought over, until about 120,000 of them were in Gaul.

How various clans had suffered from this invasion is recounted in the Commentaries. Unfortunately most of the readers of that record (immortal in spite of the arrogance and disingenuousness often displayed by the complacent author) do not appreciate that the duans and Sequanians were real people, dwelling on the outskirts of other Celtic tribes, of tribes kindred to them, and exposed to the inroads of alien clans of Germanic blood.

It is a pity that a wonderful historic document should be wasted on reluctant immature readers who only read that they may be free to run and are heedless of the contents of the words that they construe laboriously. Very few adults ever recur to a volume associated with dull school work and so an interesting story falls flat.

The Sequanians, Csar heard, were particularly disconsolate for

Ariovistus, the King of the Germans, had settled in their territory, and had seized upon a third of it, the best land in the whole of Gaul; and now he demanded that the natives should vacate another third, because a few months previously 24,000 Harudes had joined him, and he had to find homestead land for them.

Within a few years, the entire population of Gaul would be expatriated, and the Germans would all cross the Rhine; for there was no comparison between the land of the Germans, and that of the Sequanians, or between the standard of living among the former and that of the latter.

Csar was moved to sympathy for these Celtic folk thus threatened by a veritable inundation from the Rhenish valley, and especially for the Sequanians, whose lot was the most pitiable because they were afraid of harsh treatment from the dreaded rex Germanorum, if it were known that they complained. Ariovistus had wrapped himself in so much haughtiness and arrogance that he had become unbearable.

Csar was especially wrathy at this behaviour of the German leader because the duans, who were among those thus menaced by these inroads of trans-Rhine peoples, had actually been addressed as Brothers and Kinsmen, by the Roman Senate. Thus the conduct of Ariovistus was a direct insult to himself and to Rome (cap. xxxiii.).

Moreover, altruism apart, Csar foresaw that, if the Germans became accustomed to crossing the Rhine and migrating to Gaul in large numbers, there would be danger for the possessions of the Roman people.

He believed that, being fierce barbarians, they would not stop short when they had taken possession of the whole of Gaul, but would overrun the Province, as the Cimbri and Teutons had done before, and thence push their way into Italy. The Sequani were only separated from our Province by the Rhine; and be deemed it essential to repulse the danger at the earliest possible moment (cap. xxxiii.).

Accordingly, Csar proceeded immediately to take measures for self-protection. Ariovistus was already known to him. Indeed the