PENGUIN BOOKS

TIBET, TIBET

Patrick French is a writer and historian, born in England in 1966. He is the author of Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer (Beautifully written, wise, balanced, fair, funny and above all extremely original William Dalrymple), which won the Somerset Maugham Award and the Royal Society of Literature W. H. Heinemann Prize, Liberty or Death: Indias Journey to Independence and Division (French is the most impressive Western historian of modern India currently at work Herald), which won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, Tibet, Tibet: A Personal History of a Lost Land (Compassionate compelling and brilliant far and away the best book on Tibet I have read Daily Telegraph) and, The World Is What It Is: The Authorized Biography of V. S. Naipaul (One of the most gripping biographies Ive ever read Hilary Spurling), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Hawthornden Prize. His most recent book is India: A Portrait (Allen Lane, 2011).

Books by Patrick French

Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer

The Life of Henry Norman

Liberty or Death: Indias Journey to Independence and Division

Tibet, Tibet: A Personal History of a Lost Land

The World Is What It Is: The Authorized Biography of V. S. Naipaul

India: A Portrait

Patrick French

Tibet, Tibet

A Personal History af a Lost Land

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London, WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2003

Published in Penguin Books 2011

Copyright Patrick French, 2003

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-01-4-196419-5

To Ab

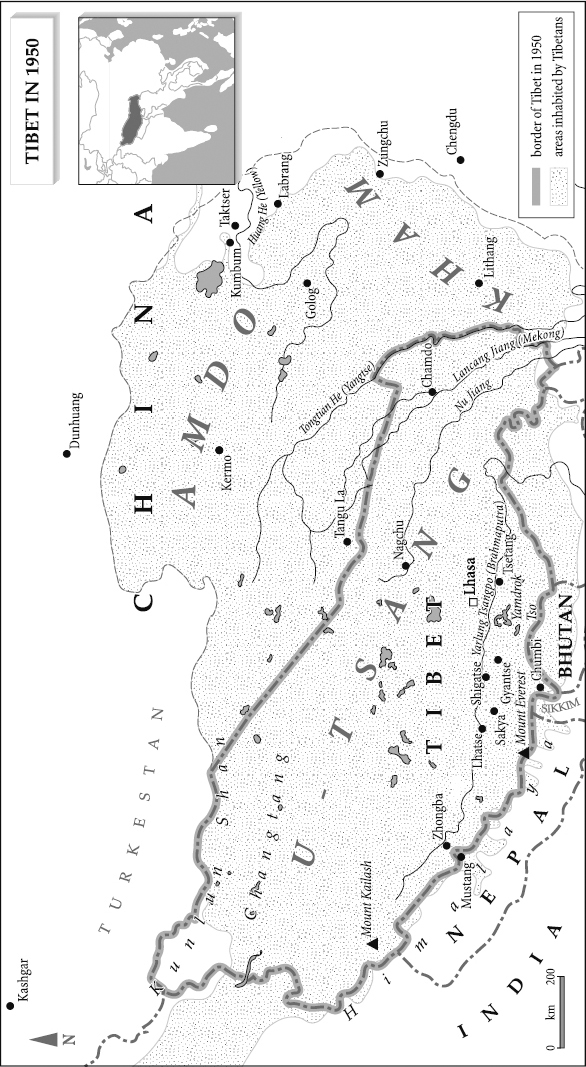

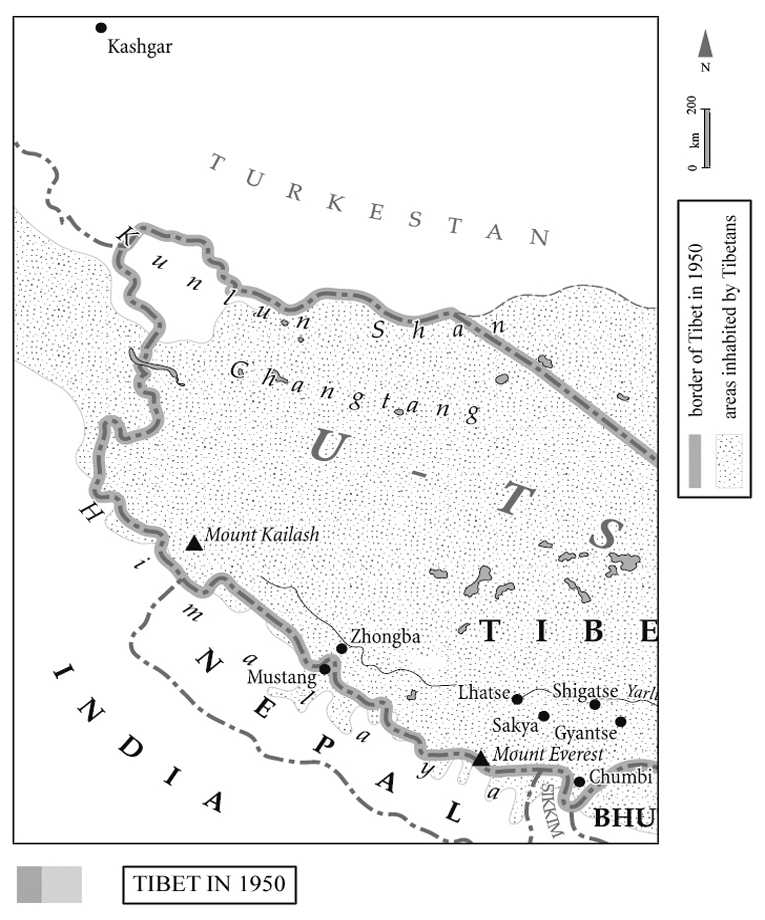

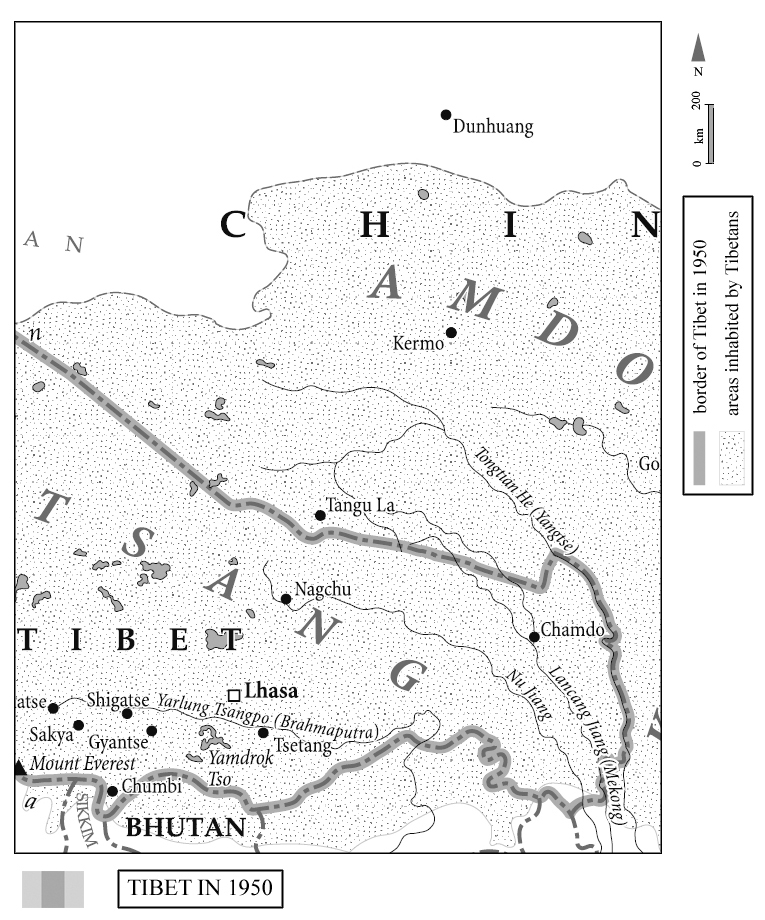

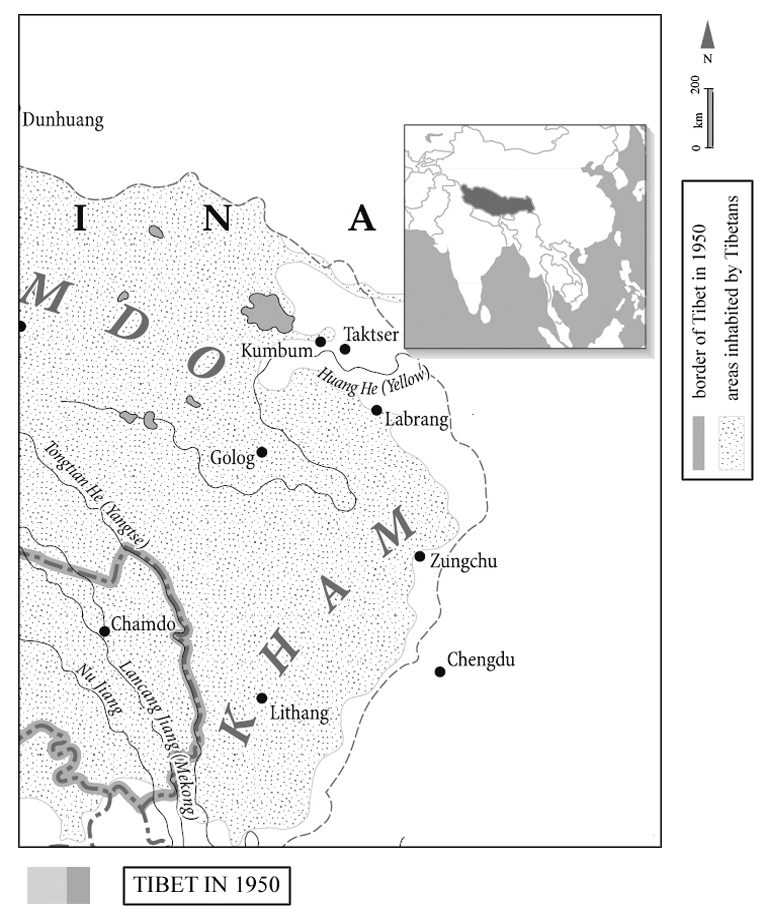

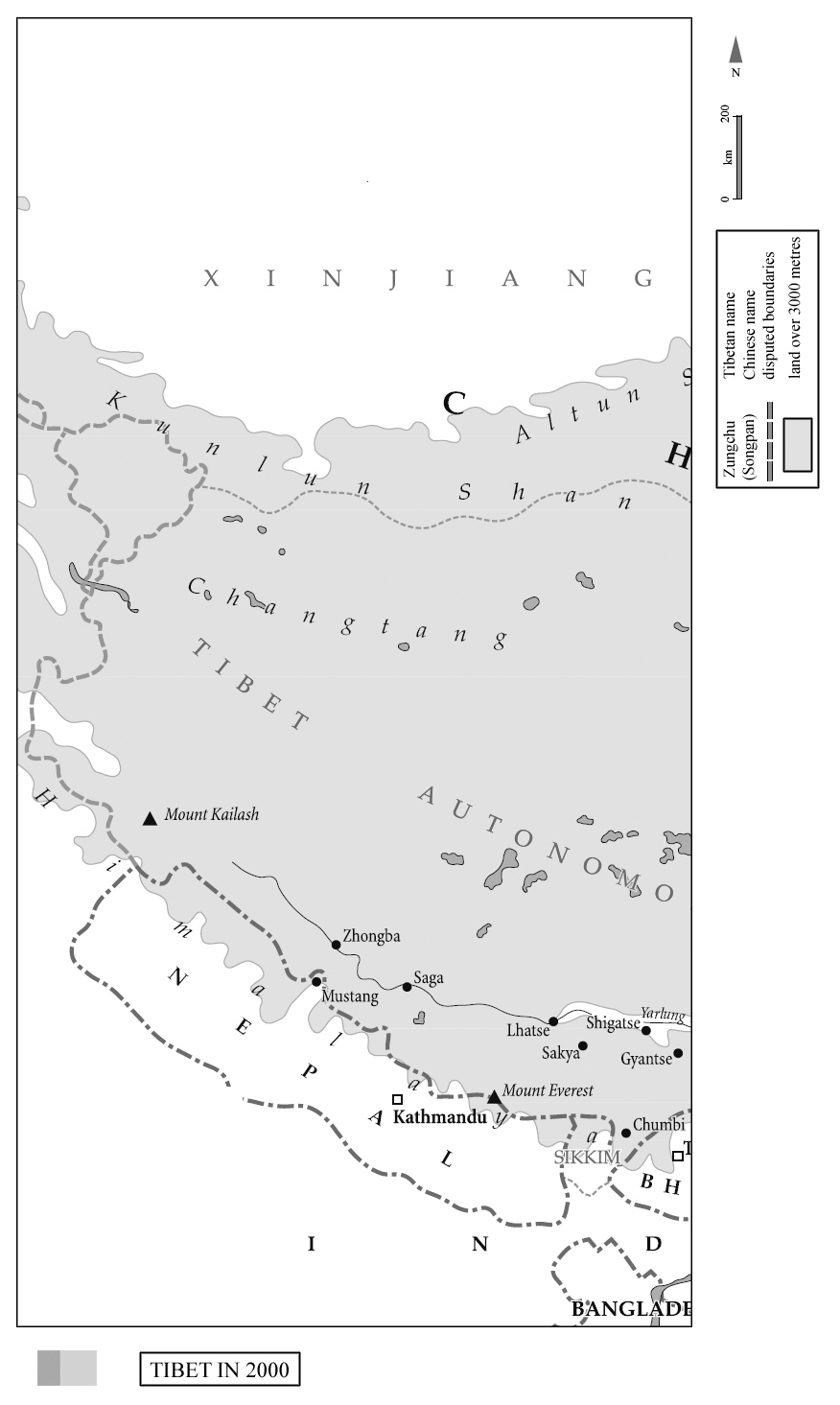

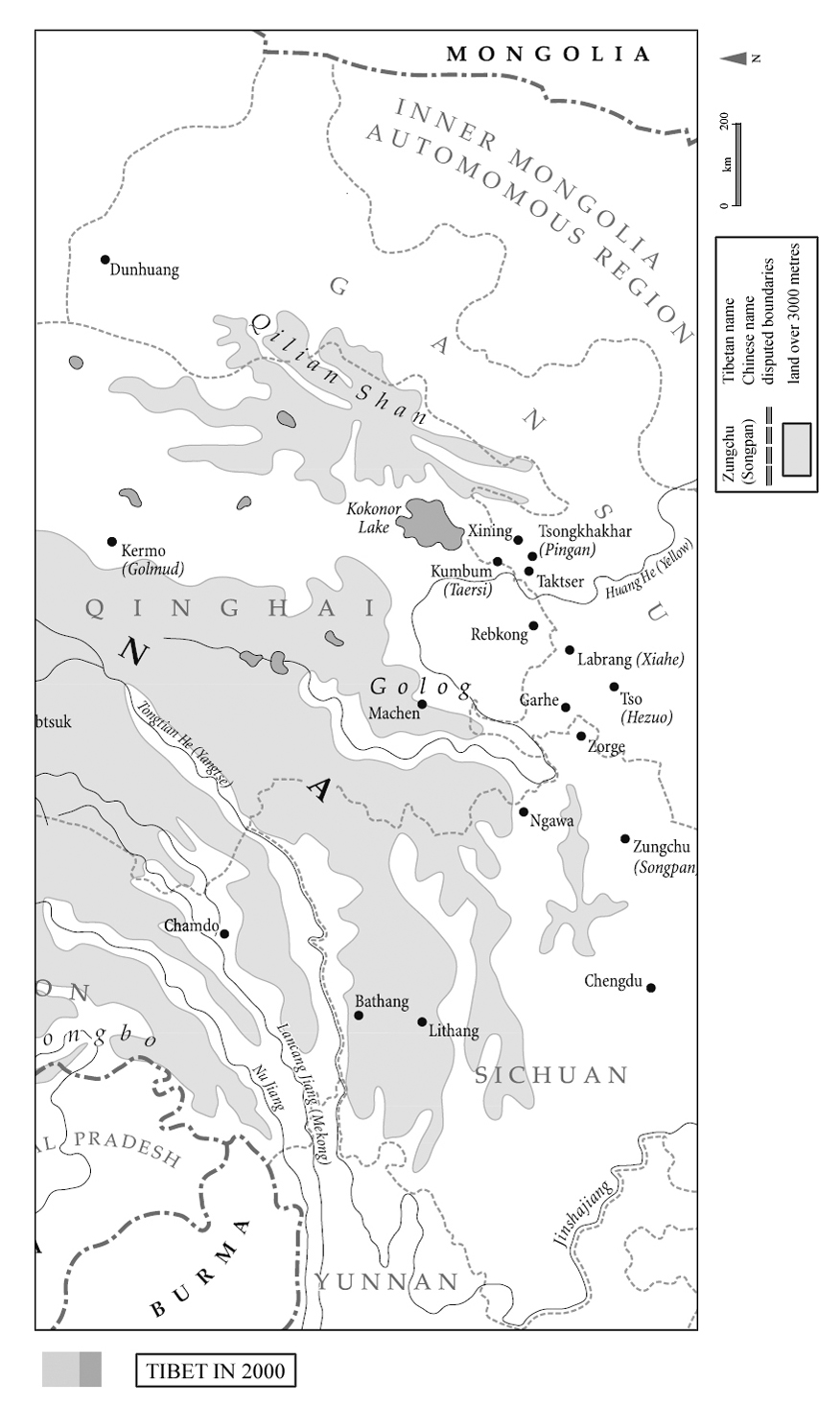

Maps

My brother said to me If you shut your eyes to a frightening sight, you end up being frightened. If you look at everything straight on, there is nothing to be afraid of.

A KIRA K UROSAWA , Something Like an Autobiography

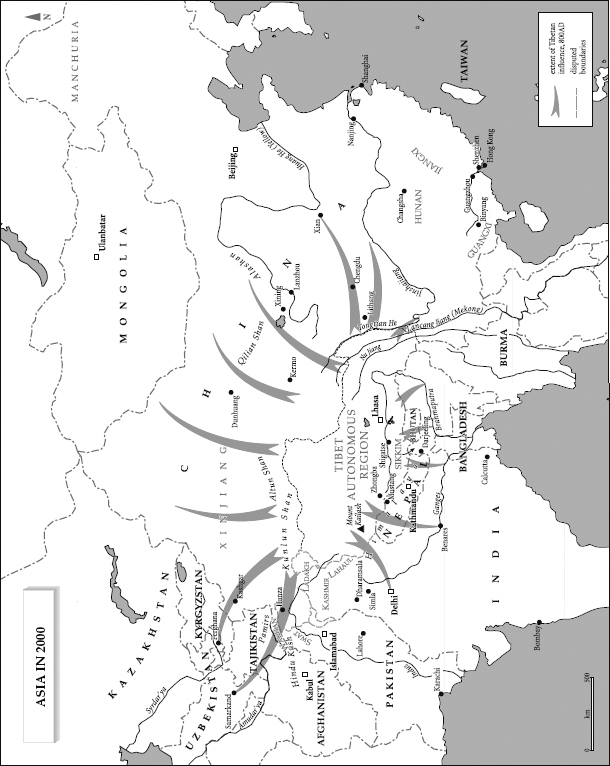

MAP 1

TIBET IN 1950

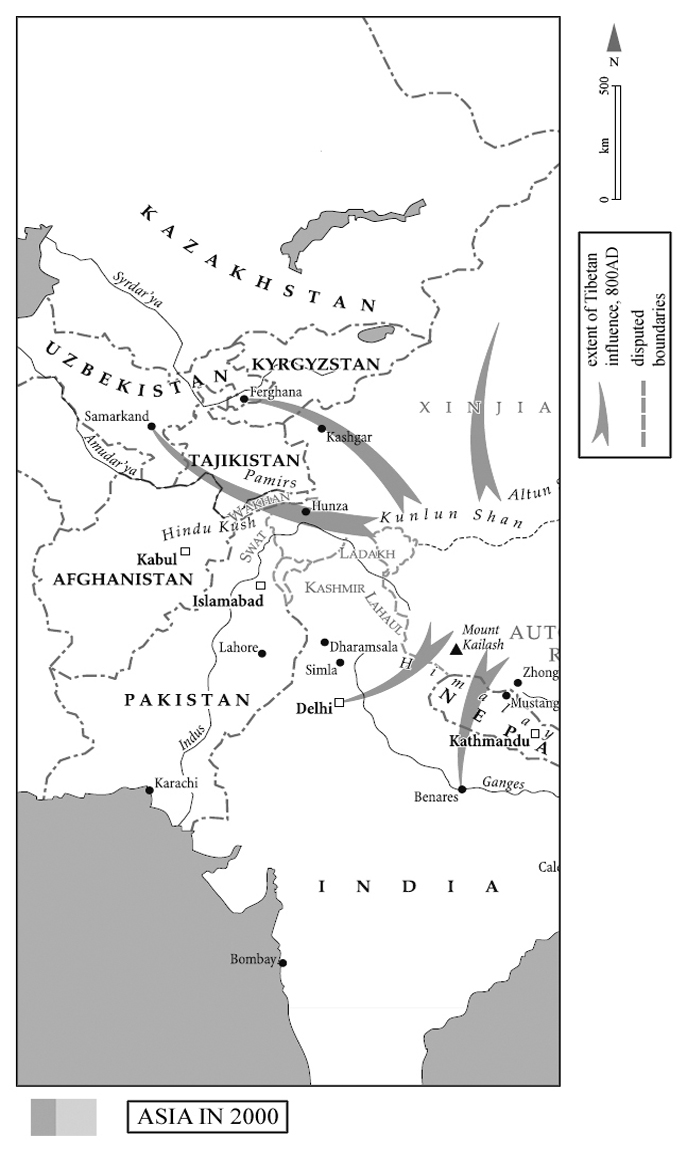

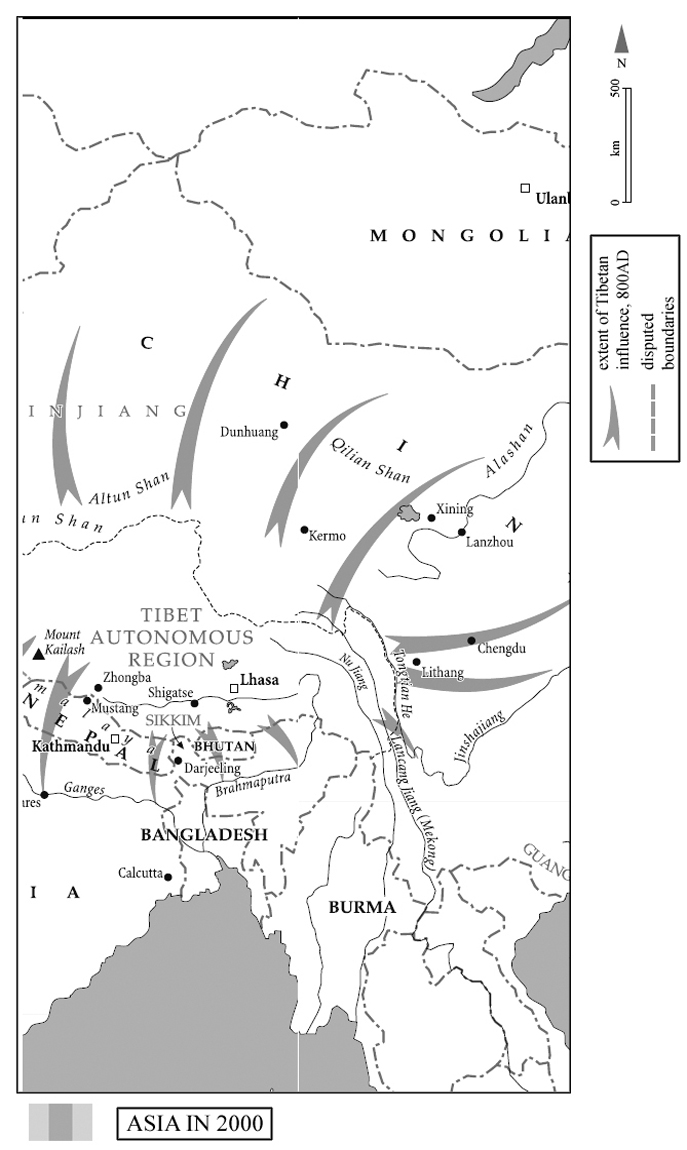

MAP 2

ASIA IN 2000

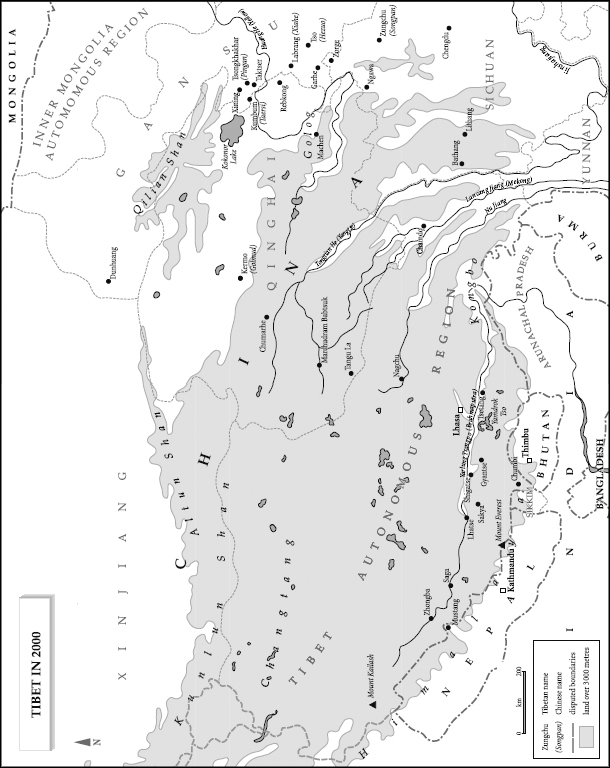

MAP 3

TIBET IN 2000

I

One

I was living in a room at Tsechokling monastery, below the Himalayan village of McLeod Ganj, the centre of exiled Tibetan life. It was 1987, and demonstrations were breaking out in Tibet for the first time in decades. At the end of the summer I had to return to Europe, but for the moment I was just where I wanted to be. It was simple. Each morning I would wake early, wash in cold water and walk down through the forest to the library above Dharamsala. The place was poor and insanitary at that time, with hunched old women clutching rosaries, and second-generation hustlers parading in slogan T-shirts and shades. There were a few post-hippie travellers, some Hindu pilgrims who came to visit the shrine at Bhagsunath, and students of Tibetan culture from places like Israel and Japan.

There was one man at Tsechokling who was attached to the monastery, but was not a monk. He lived alone in a hut he had built on the hillside, and could be seen herding cows, collecting firewood and occasionally helping out in the smoke-filled monastery kitchen. His name was Thubten Ngodup. He was quiet and shy, with a worn face that was marked with experience: he had escaped from Tibet after the Chinese Communist invasion of 1950, and worked in pitiful conditions on a road gang before joining the Tibetan section of the Indian army.

Ngodup had learned to cook when he was a soldier, and one of the monks suggested he might make a living by providing food for the occupants of the few monastery guest rooms. I was asked to help him set up the operation. We communicated in fits and starts, using fragments of shared language; looking back, I think that he felt awkward dealing with a foreigner during our fleeting, symbiotic friendship. A feasible menu was agreed (tea, soup, omelette, momo, shabalay, thukpa) which I copied out in English and distributed to likely customers. The arrangement worked well. Ngodup became dedicated to the purchase and preparation of food, anxious, maybe too anxious, in an ex-military sort of way, to provide perfect service. He had a role, and it made life easier for him.