My brother said to me If you shut your eyes to a frightening sight, you end up being frightened. If you look at everything straight on, there is nothing to be afraid of.

ONE

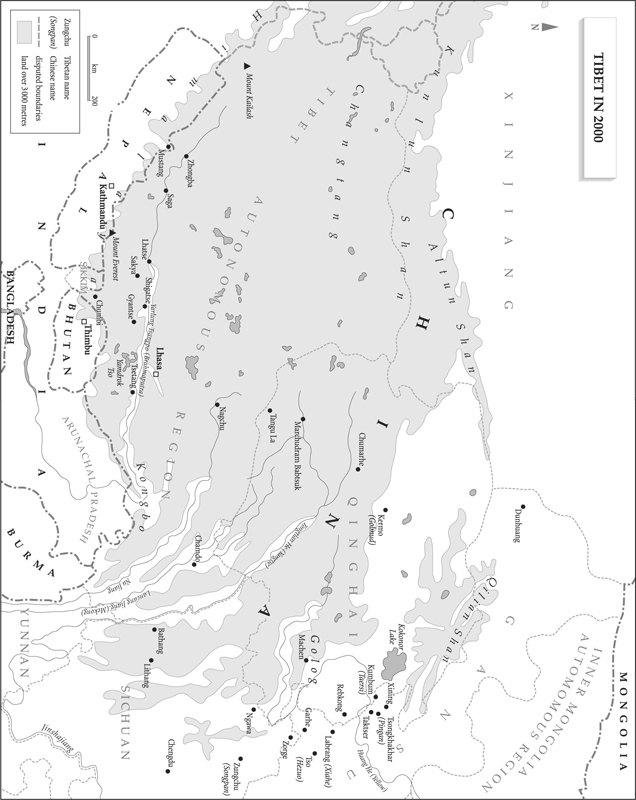

I was living in a small room at Tsechokling monastery, below the Himalayan village of McLeod Ganj, the centre of exiled Tibetan life. It was 1987, and demonstrations were breaking out in Tibet for the first time in decades. At the end of the summer I had to return to Europe, but for the moment I was just where I wanted to be. It was simple. Each morning I would wake early, wash in cold water, and walk down through the forest to the library above Dharamsala. The place was poor and insanitary at that time, with hunched old women clutching rosaries, and second-generation hustlers parading in slogan T-shirts and shades. There were a few post-hippie travellers, some Hindu pilgrims who came to visit the shrine at Bhagsunath, and students of Tibetan culture from places like Israel and Japan.

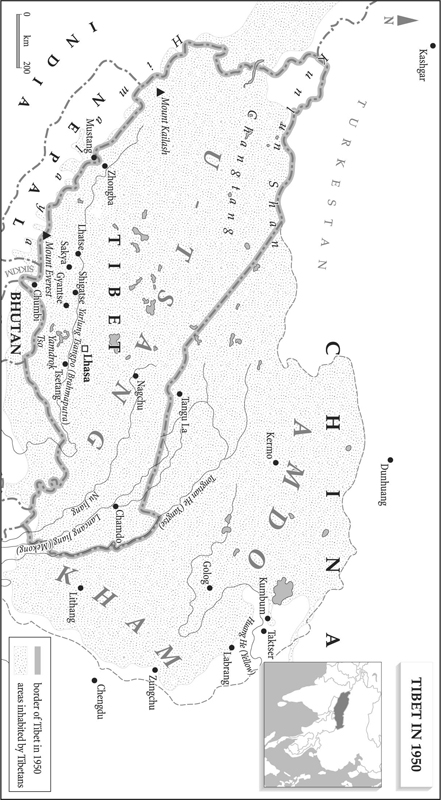

There was one man at Tsechokling who was attached to the monastery, but was not a monk. He lived alone in a hut he had built on the hillside, and could be seen herding cows, collecting firewood and occasionally helping out in the smoke-filled monastery kitchen. His name was Thubten Ngodup. He was quiet and shy, with a worn face that was marked with experience: he had escaped from Tibet after the Chinese Communist invasion of 1950, and worked in pitiful conditions on a road gang before joining the Tibetan section of the Indian army.

Ngodup had learned to cook when he was a soldier, and one of the monks suggested he might make a living by providing food for the occupants of the few monastery guest rooms. I was asked to help him set up the operation. We communicated in fits and starts, using fragments of shared language; looking back, I think that he felt awkward dealing with a foreigner during our fleeting, symbiotic friendship. A feasible menu was agreed (tea, soup, omelette, momo, shabalay, thukpa) which I copied out in English and distributed to likely customers. The arrangement worked well. Ngodup became dedicated to the purchase and preparation of food, anxious, maybe too anxious, in an ex-military sort of way, to provide perfect service. He had a role, and it made life easier for him.

You can see Ngodup at Tsechokling as the sun comes up over the wooden houses high on the ridge, carrying a bashed aluminium tray, on it china cups and saucers, a bowl of sugar and a beaker of hot milk, a cracked pot of tea and a plate of cooling buttered toast. He stands, leaning over the table, half-smiling and half-embarrassed, placing the breakfast things before us, bowing slightly, instinctively, in the Tibetan way. When he has finished, he picks up the tray and, holding it flat against his side, goes down the stone steps of the guest house, back towards the monastery kitchen, hitching up the patched brown trousers that hang loosely from his hips as he walks. He is forty-nine years old.

E leven years later, during a demonstration in New Delhi, Ngodup made his choice. By his own free will, he ran to a hut where the cleaning fluids for the banners were kept, and poured gasoline across his body, drenching his clothes, his head, his hair, his face, the smell of the clouding vapour enough to make you reel. With a spark and a roar, he burst from the hut and ran into the square, blazing.

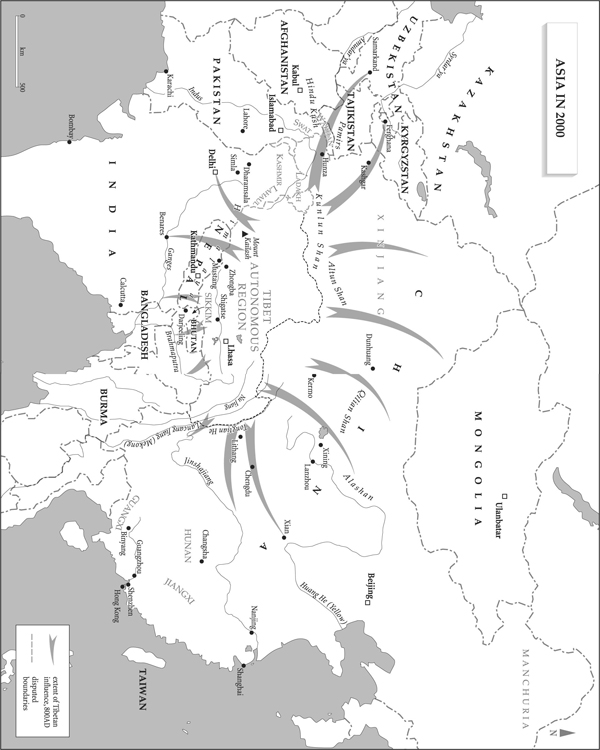

The date was 27 April 1998, just as the sun came up. Six Tibetan refugees were holding a hunger-strike at Jantar Mantar, encouraged by hundreds of supporters and frequent visits from the worlds press. The target of their protest was the poor, useless United Nations. There were several demands: a plebiscite over Tibets future, a rapporteur to investigate human rights abuses, and a debate on long-forgotten UN resolutions.

The hunger-strike had been going on for forty-nine days, and several people were close to death. Ngodup was in the next batch of protesters, lined up ready to replace those who died. There was a hitch: a Chinese visitor was expected. The chief of the General Staff of the Peoples Liberation Army, Fu Quanyou, was arriving in India on an official visit, and the authorities did not want his stay to be marred by dying Tibetans. Indian police were told to clear the site. As day broke, the police crashed in, wielding boots and lathis, dragging hunger-strikers into ambulances and beating back protesters. Choyang Thar-chin, an official from the exiled Tibetan government in Dharamsala, picked up a video camera and began to film the scuffles.