A LSO BY P ATRICK F RENCH

YOUNGHUSBAND

The Last Great Imperial Adventurer

THE LIFE OF HENRY NORMAN

LIBERTY OR DEATH

Indias Journey to Independence and Division

TIBET, TIBET

A Personal History of a Lost Land

First published 2008 by Picador

This electronic edition published 2012 by Picador

an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Road, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-330-46493-2 EPUB

Copyright Patrick French 2008

The right of Patrick French to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The Macmillan Group has no responsibility for the information provided by any author websites whose address you obtain from this book (author websites). The inclusion of author website addresses in this book does not constitute an endorsement by or association with us of such sites or the content, products, advertising or other materials presented on such sites.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit www.picador.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that youre always first to hear about our new releases.

MG

List of Illustrations

F IRST S ECTION

S ECOND S ECTION

Introduction

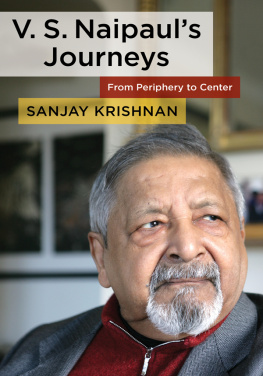

When V.S. Naipaul won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2001, each country responded in its own way. The president of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago sent a letter of congratulation on heavy writing paper; an Iranian newspaper denounced him for spreading venom and hatred; the Spanish prime minister invited him to drop by; Indias politicians sent adulatory letters, with the president addressing his to Lord V.S. Naipaul and the Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan sending a fax of congratulation from Los Angeles; the New York Times wrote an editorial in praise of an independent voice, skeptical and observant; the British minister for culture, media and sport sent a dull, late letter on photocopying paper, and BBC Newsnight concentrated on Inayat Bunglawala of the Muslim Council of Britain, who thought the award a cynical gesture to humiliate Muslims. At this point in British history, when the sensational and immediate mattered above all else and fame was becoming more important than the achievements that might give rise to fame, Naipauls half-century of work as a writer seemed less significant than his reputation for causing offence.

My background is at once exceedingly simple and exceedingly confused, he suggested in his Nobel lecture.dispensation in the aftermath of empire. His achievement was an act of will, in which every situation and relationship would be subordinated to his ambition. His public position as a novelist and chronicler was inflexible at a time of intellectual relativism: he stood for high civilization, individual rights and the rule of law.

This was not an unusual position for someone of his background to be taking, but in Europe in the early twenty-first century it became extraordinary, aided by Naipauls tendency to caricature himself in public, outside his books. He said, or was said to have said, that Africa had no future, Islam was a calamity, France was fraudulent and interviewers were monkeys. If Zadie Smith of White Teeth fame optimistic and presentable was a white liberals dream, V.S. Naipaul was the nightmare. Rather than celebrate multiculturalism, he denounced it as multi-culti, made malign jokes about people with darker skin than himself, blamed formerly oppressed nations for their continuing failure and attacked Prime Minister Tony Blair as a pirate who was imposing a plebeian culture on Britain. The only Blacks he associated with now were Conrad and Barbara. For a successful immigrant writer to take such a position was seen as a special kind of treason, a betrayal of what should be a purely literary genius. The critic Terry Eagleton complained Great art, dreadful politics while the reggae poet Linton Kwesi Johnson said, Hes a living example of how art transcends the artist cos he talks a load of shit but still writes excellent books.

Naipaul was initially unwilling to take the call from Stockholm, since he was cleaning his teeth. When the secretary of the Nobel committee got him on the line, he enquired, Youre not going to do a Sartre on us, and refuse the prize? Naipaul accepted, and put out a statement that the Nobel was, a great tribute to both England, my home, and India, the home of my ancestors. There was no mention of Trinidad. Asked why not, he said it might encumber the tribute, which provoked the Barbadian writer Later, after I had visited Trinidad, I realized this style of conversation was not rare in the Caribbean. It was what Trinidadians call picong, from the French piquant, meaning sharp or cutting, where the boundary between good and bad taste is deliberately blurred, and the listener sent reeling.

Around this time, I was asked to write V.S. Naipauls biography. I was hesitant; I was finishing another book, and saw it would be a big and potentially fraught project, perhaps the last literary biography to be written from a complete paper archive. His notebooks, correspondence, handwritten manuscripts, financial papers, recordings, photographs, press cuttings and journals (and those of his first wife, Pat, which he had never read) had in 1993 been sold to the University of Tulsa in Oklahoma, a place famous for its hurricanes and the worst race riot in Americas history.

I had met Naipaul a few times before this, once in England and later in Delhi while writing an article for the New Yorker magazine. Tarun Tejpal, a friend who worked as a journalist, telephoned and invited me to a press conference, saying he would collect me from my hotel in ten minutes. His car, shabby against the grand hotel limousines, drew up under a colonnade. I climbed into the back and noticed that I was sitting beside Sir Vidia Naipaul. He was wearing many layers of clothing and a tweed jacket, despite the heat. He held a trilby hat carefully in his lap. A roll-neck sweater merged with his beard, completing the impression that he was fully covered. Nadira, the second Lady Naipaul, was sitting in the front beside Tarun. She asked me about the article I was writing, and I mentioned some trouble I was having with the magazines celebrated fact-checkers. Dont let the New Yorker worry you, said Naipaul, enunciating each syllable of each word in his modulating voice, part West Indian, part Queens English. The New Yorker knows nothing about writing. Nothing. Writing an article there is like posting a letter in a Venezuelan postbox; nobody will read it. He paused, and continued, We were talking about the funeral of Princess Diana. The princess had died some months earlier. What were your thoughts about it?

From everything I knew of Naipaul, I imagined he would hate the sentiment swirling around the dead princess, and view her as another Evita Pern. He was watching me through narrowed eyes with a would-be benign smile playin dead to catch corbeau alive, to use the Caribbean phrase. We were in a Delhi traffic jam by now, horns honking. I was jet-lagged; I thought I might be honest.

Next page