The Icelandic alphabet has three letters that are missing in modern English, although Old English had them. The letter (called eth) sounds like the voiced th in the; (thorn) is an unvoiced th, as in thought; (ash) makes the long i sound. A few Icelandic words appear in italics in this book but, for ease of reading, I have anglicized all the Icelandic names, changing the to d, to th, and to ae, and omitting accents. (I have also omitted accents from names in other foreign languages; on the acknowledgments page and in the list of sources, the names are given their proper spellings.) I have retained the nominative endings (as in Sigridur) for most modern Icelandic names (the exception being place-names ending in -fjord); for saga characters, I have dropped the endings (turning Gudridur into Gudrid) to be consistent with other saga translations. For names known by several spellingssuch as Eric, Erik, or Eirik the RedI have chosen the Icelandic version. Most Icelandic last names are patronymics, made by adding son or dottir to the possessive form of the fathers name. Gudrid Thorbjarnardottir is, literally, Gudrid, daughter of Thorbjorn. Leif Eiriksson is Leif, son of Eirik. For this reason, modern Icelanders always go by first names, no matter how formal the situation. I have followed their practice.

Prologue

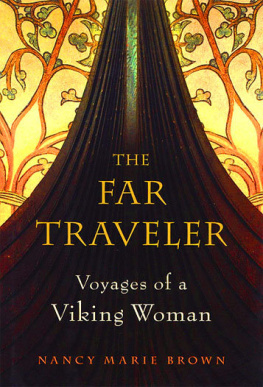

Gudrid the far-Traveler

Making a voyage to Vinland was all anyone talked about that winter. They all kept urging Karlsefni to go, Gudrid as much as the others.

The Saga of the Greenlanders

A THOUSAND YEARS AGO, AN OLD WOMAN NAMED GUDRID stood on the threshold of her house contemplating her next voyage. Now I stand there in her stead, looking out at a long bank of treeless mountains. A pass to the east leads up along a leaping stream into high pastures that, as I watch, are lit by a shaft of sunlight and, as quickly, fade back to gray. I turn away, get back to work. I have spent the summer with a team of archaeologists, uncovering the remains of Gudrids house with shovel and trowel, and today, in a misty cold rain, my Icelandic sweater smeared with mud, I must help rebury it.

For five long weeks we traced the outline of this Viking longhouse, finding the four rooms Gudrid lived in, the doors she entered and left by, our only clues the colors and patterns in the hard-packed earth. The house, built of blocks of turf or sod laid up in a herringbone pattern, was abandoned and flattened sometime in the half century between 1050 and 1104. The date that sticks in my mind is 1066, the end of the Viking Age. In the years since then, Gudrids house was buried by windblown soil and so preserved for the archaeologists to find, eight inches below the plow zone in the hayfield at Glaumbaer, Farm of Merry Noise, in northern Iceland. For the scientists, laying landscape fabric on top of the walls and piling dirt back on by the bucketful is an ordinary end-of-the-season chore; putting the site to bed, as they say. They dont even complain about the rain.

To me, it is the untimely end of a grand adventure. True, we have photographs and drawings. The computers store a floor plan of Gudrids house keyed to a GPS grid, so it can easily be found again. But a remote-sensing device called ground-penetrating radar had given us tantalizing images of what could be a flagstone patio outside Gudrids front door and the central hearth in her main hall. Those floor-level features are a foot deeper than we had dug this summer, not to mention the needles, combs, spindle whorls or spoons, glass beads, brass pins, and parts of a loom that we could expect to find forgotten on a Viking womans floor. There wouldnt be much to collect. Gudrids family had not left in a hurry, and they hadnt moved far, just a few hundred feet up the hill to build a grander house overlooking the river plain. They would have taken all their valuables with them. But there might have been enough to let me feel I had held in my hand something Gudrid herself had dropped.

Then there was the puzzle of the horse skull, found two days ago in the middle of what should be Gudrids weaving room. The rest of the horse might be there, too, and perhaps even a human skeleton, for in Viking Iceland a man or woman was often buried with a favorite horse. And other graves had been found just down the valley, dug into a ruined longhouse. But the archaeologists, knowing they were out of time and money, were practical. They recorded the skulls position and covered it right back up. I seem to be the only one fretting that there is no moneyand no planto reopen the dig next year.

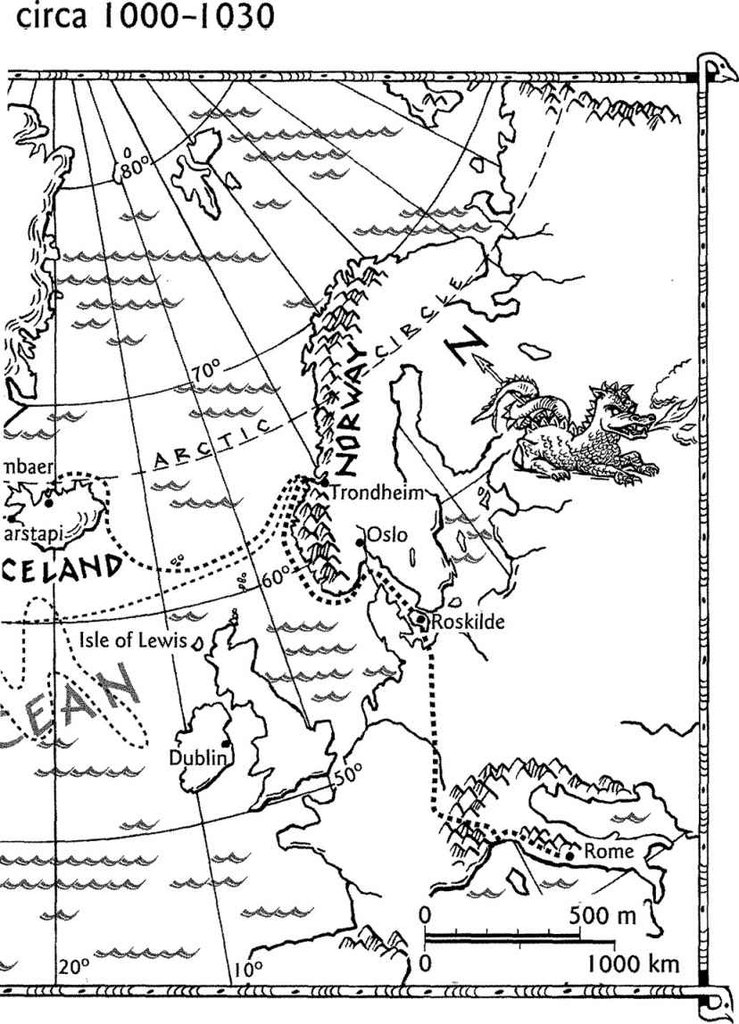

But the Gudrid I imagine, standing on her threshold a thousand years ago, watching the winds comb the woolly clouds across the flat-topped mountains, would not have been sad. She would have turned to look north, where the valley widens out to sea, and smiled. For her, a new adventure was beginning. Despite her age (she was soon to be a grandmother), she was on her way across the sea to Norway and then south to Rome.

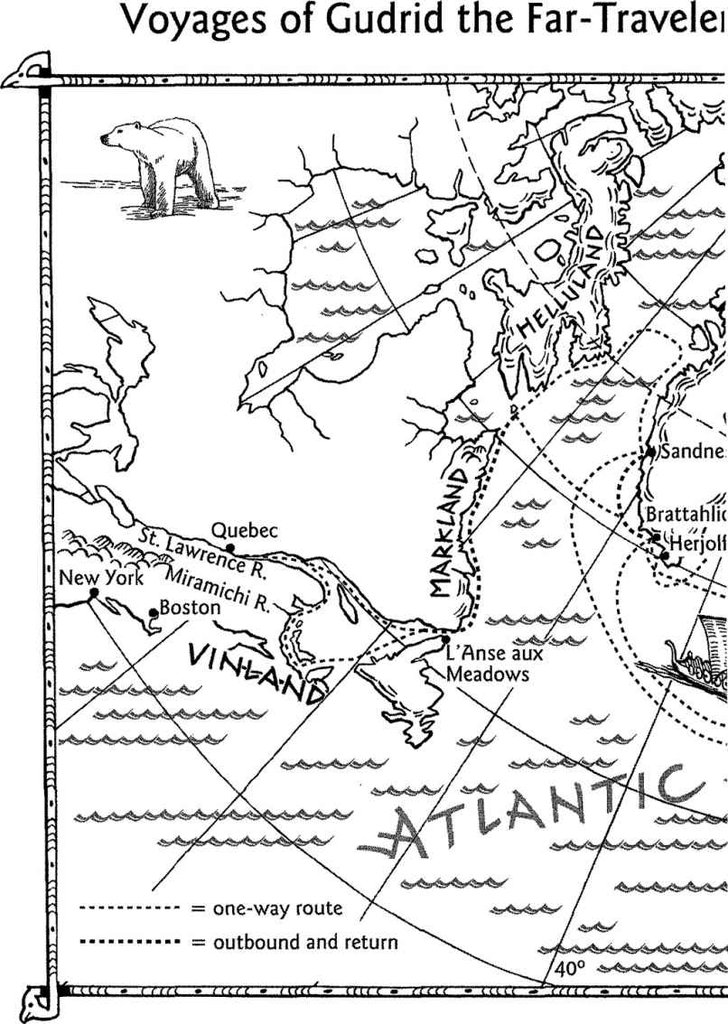

This pilgrimage was not the firstor the farthestof her voyages. Twenty years before, she had sailed west from Greenland off the edge of the known world. She was nineteen, newly wed for the second or third time and pregnant for the first. With her were her husband, Thorfinn Karlsefni, and three Viking crews in clinker-built boats. They were sailing to Vinland, a fabulous land that Leif Eiriksson, son of Greenlands founder Eirik the Red, had washed up on a few years back, when he was caught in a summer storm, sailing west across the icy North Atlantic from Norway. It was Gudrids second attempt to get to Vinland. She meant to settle in this New World.

At summers end, the crews beached their ships on a grassy shore and built a longhouse out of turf; there Gudrid gave birth to her son Snorri. For three years they explored their Vinland, or Wine Land. They found salmon and halibut, tall trees and lush grasslands, wine grapes, and a grain like wheat. They saw islands full of eider ducks, bears, or foxes, mountains and marvelous beaches, fjords with fierce currents and wide tidal lagoons. And they met strangers whose language they could not understand, strangers who had never seen an axe or a bull, who were delighted by the taste of milk and traded packs full of furs for thin strips of red wool cloth; strangers who fought with stone-tipped arrows and whose numbers were overwhelming.