Also by Nancy Marie Brown

The Abacus and the Cross: The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages

The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman

Mendel in the Kitchen: A Scientists View of Genetically Modified Food

(with Nina Fedoroff)

A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse

Song

of the

Vikings

SNORRI AND THE MAKING OF NORSE MYTHS

NANCY MARIE BROWN

SONG OF THE VIKINGS

Copyright Nancy Marie Brown, 2012.

All rights reserved.

First published in 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN in the U.S. a division of St. Martins Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe, and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS.

Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world.

Palgrave and Macmillan are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe, and other countries.

ISBN: 978-0-230-33884-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brown, Nancy Marie.

Song of the Vikings : Snorri and the making of Norse myths / Nancy Marie Brown.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-230-33884-5 (hardback)

1. Snorri Sturluson, 1179? 1241Criticism and interpretation. 2. Old Norse literatureInfluence. 3. Literature and societyScandinaviaHistory. I. Title.

PT7335.Z5B76 2012

839.63dc23

2012012031

A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.

Design by Letra Libre

First edition: October 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America.

Contents

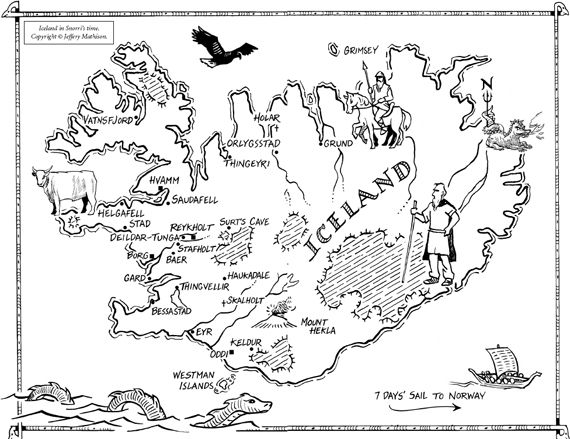

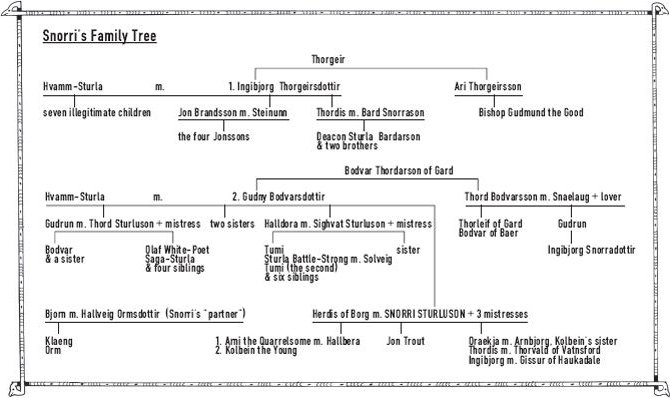

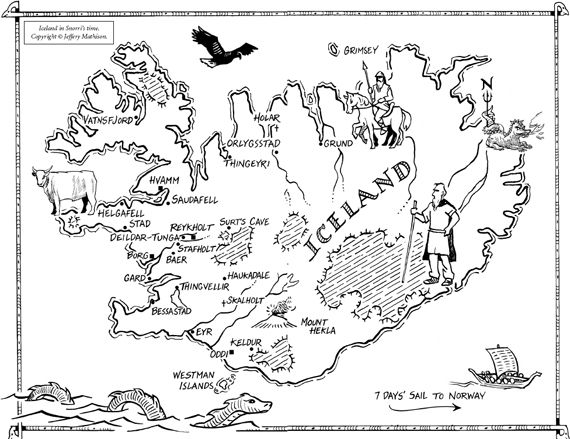

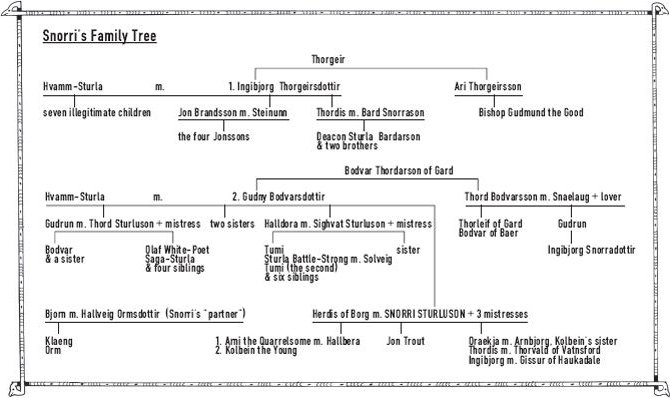

Design by Jeffery Mathison and Newgen KnowledgeWorks.

GANDALF

What troubles the gods? What troubles the elves?... Would you know more, or not?

Snorri, Edda

In the late 1920s J. R. R. Tolkien provoked an argument. Opposing him, among others, was C. S. Lewis. Tolkien had not yet written The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. Lewis had not yet written The Chronicles of Narnia. They were debating the appropriate curriculum for English majors at Oxford University, where they both taught.

Tolkien believed too much time was spent on dull and unimportant writers like Shakespeare, whom Lewis revered. Instead, Tolkien thought, students should read Snorri Sturluson.

Who?

And not only Snorri but the other fine authors of the Icelandic sagas and the the Eddic poems. And the students should read them in Old Norse.

Lewis had read the mythological tales from Snorris Edda in English as a boy. He found the Norse myths more compellingas stories, he saidthan even the Bible. Like Tolkien, he was drawn to their Northernness: to their depictions of dragons and dwarfs, fair elves and werewolves, wandering wizards, and trolls that turned into stone. To their portrayal of men with a bitter courage who stood fast on the side of right and good, even when there was no hope at all.

Its even better in the original, Tolkien said. He had been reading Old Norse since his teens. He loved the cold, crisp, unsentimental language of the sagas, their bare, straightforward tone like wind keening over ice. Reading Snorri and his peers was more important than reading Shakespeare, Tolkien argued, because their books were more central to our language and our modern world. Egg, ugly, ill, smile, knife, fluke, fellow, husband, birth, death, take, mistake, lost, skulk, ransack, brag, and law, among many other common English words, all derived from Old Norse. As for Snorris effect on modernity, it was soon to mushroom.

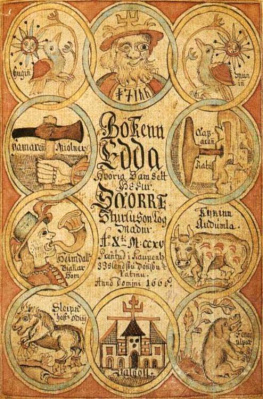

Tolkien convinced his colleagues to substitute Snorri for Shakespeare by starting a club called the Kolbtar. A coalbiter in the sagas is a lad who lounges by the fire instead of working; roused, he transforms into a hero, an outlaw, or both. These academic coalbiters lounged by the fire translating medieval Icelandic poetry and prose aloud. They began with the myths in Snorris Edda. A few years later, having finished the major Icelandic sagas and the mythological verse in the Poetic Edda, the club morphed into the Inklings, where they read their own works.

One of those works was The Hobbit.

I first heard The Hobbit read aloud when I was four. I discovered The Lord of the Rings when I was thirteen. Through college, Tolkien was my favorite author, his books my favorite works of literaturedespite the scorn such a confession brought down on an English major at an American university in the late 1970s, where fantasy was derided as escapist and unworthy of study.

Then I took a course in comparative mythology. To learn about the gods of Scandinavia, I was assigned The Prose Edda, a collection of mythological tales drawn from the work of the thirteenth-century Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson. Page forty-one in the paperback edition of Jean Youngs 1954 translation was the turning point of my literary life.

I read: The gods seated themselves on their thrones and held counsel, and remembered how dwarfs had quickened in the earth.... By the decree of the gods they acquired human understanding and the appearance of men, although they lived in the earth and in rocks. Modsognir was the most famous, and next to him Durin.

Durin?

I knew that name. In the list of dwarfs that filled the rest of page forty-one and spilled onto forty-two, I recognized several more: Bifur, Bafur, Bombor, Nori, Ori,... Oin... Gandalf

Gandalf? I sucked in my breath. What was Tolkiens wizard doing in medieval Iceland?

I read Tolkiens biography and learned about the coalbiters. I met a professor with a bookcase full of Icelandic sagas that he lent me, one after the next. When I ran out of translations, I found another professor to teach me Old Norse. As I contemplated earning a PhD, I went to Iceland and, like William Morris and many other writers before and since, traveled by horseback through the wind-riven wilderness to the last homely house. I wondered why Icelands rugged, rain-drenched landscape seemed so insistently familiaruntil I learned that Tolkien had read Morriss Journals of Travel in Iceland, 18711873 and created from them the character of the home-loving hobbit Bilbo Baggins and his soggy ride to Rivendell.

The name of the wizard, Tolkien acknowledged, he had plucked from Snorris list of dwarfs, though Gandalf had nothing dwarfish about him. (In the first draft of The Hobbit, the wizards name was Bladorthin.) Gandalfs physical description and his character, Tolkien wrote, were Odinic. They derived from Snorris tales of the Norse god Odin, the one-eyed wizard-king, the wanderer, the shaman and shape-shifter, the poet with his beard and his staff and his wide-brimmed floppy hat, his vast store of riddles and runes and ancient lore, his entertaining after-supper tales, his superswift horse, his magical arts, his ability to converse with birds.

Next page