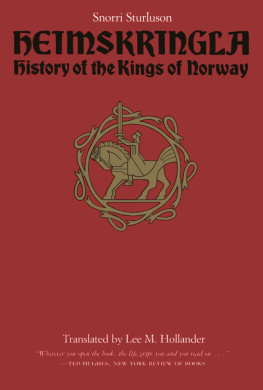

HEIMSKRINGLA

History of the Kings of Norway

HEIMSKRINGLA

History of the Kings of Norway

by Snorri Sturluson

Translated with Introduction and Notes by

Lee M. Hollander

Stolen and delivered by

[DerHammer]

Twitter: Twitter.com/HammerDer

Kickass.to: Kickass.to/user/DerHammer

Contents

Ynglinga saga

Hlfdanar saga Svarta

Haralds saga Hrfagra

Hkonar saga Ga

Haralds saga Grfeldar

lfs saga Tryggvasonar

lfs saga Helga

Magnss saga ins Ga

Haralds saga Sigurarsonar

lfs saga Kyrra

Magnss saga Berfoetts

Magnssona saga

Magnss saga Blinda ok Harald Gilla

Haraldssona saga

Hkonar saga Heribreis

Magnss saga Erlingssonar

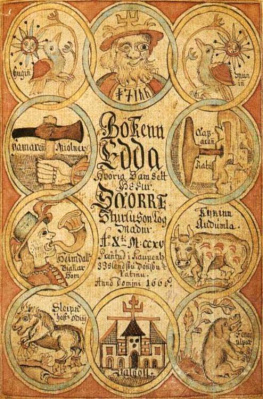

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The illustrations in this volume are by Halfdan Egedius, Christian Krohg, Gerhard Munthe, Eilif Peterssen, Erik Werenskiold, and Wilhelm Wetlesen. They are reproduced courtesy of Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, Oslo, Norway.

LIST OF MAPS

Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and the Baltic Countries)

Introduction

In Snorri Sturluson the northern world has had a historian who in many ways can be compared with Thucydides and in some is in nowise inferior to his Greek counterpart. And considering the great disparity in general culture and intellectual advancement between his times and Periclean Greece we may marvel all the more at Snorris genius. His work is unique in European historiography in presenting us with a continuous account of a nations history from its beginnings in the dim prehistoric past down into the High Middle Ages.

The protagonists of both nature and nurture as influence on the development of a man will find support in the ancestry and the upbringing of Snorri. He was born in 1179 (or 1178) at Hvamm in western Iceland. His father, Sturla Thortharson, was a shrewd and grasping landholder, descended in a direct line from that canny leader, Snorri the Priest, who in many ways played a dominant part in early Icelandic affairs. Snorris mother, Guthn, was the daughter of Bothvar Thortharson, who reckoned among his ancestors the redoubted fighter and great poet, Egil Skallagrmsson, as well as the lawspeaker and able skald, Marks Skeggjason; while on the spindle side she was likewise a descendant of Snorri the Priest. So much for his ancestry.

While Snorri was still a child of three or four there occurred an incident which was to have a decisive influence on his life and career. As we are told in the Sturlunga saga, that rather chaotic but most informative chronicle of the internecine struggles in Iceland during the thirteenth century, a dispute had arisen about an inheritance between a certain priest, Pl Slveson, and Bothvar. The latters case was being argued by Sturla when, exasperated by the lengthy wrangling, Thorbjorg, Pls wife, rushed at Sturla with a knife, exclaiming, Why shouldnt I make you like him you most want to be like, and that is thin, But later, through the intercession of the great Jn [Jan] Loptsson, it was lowered considerably. To mollify Sturla, Jn offered to foster his youngest son, Snorri, at his estate of Oddi.

Now to grasp the import of this offer we must bear in mind that he who offered fosterage to another mans child thereby acknowledged himself inferior in rank. As a fact Jn Loptsson was at the time the most powerful as well as the most high-born chieftain in Iceland. Jons father, Lopt Smundarson, had married a daughter of King Magns Barelegs of Norway; and his grandfather, Smund, a kinsman of the Earl of Mr, enjoyed an almost legendary respect for his wisdom and for the learning he had acquired when studying in France. Oddi, the family estate in south Iceland, had since Smunds time been the seat of the highest culture the island could boast of, and functioned informally as a kind of school for clerics. It was a place where a knowledge of the common law of the land was handed down and in whose atmosphere the study of history, of skaldship, and of course of Latin, were cultivated.

We do not know why Jn offered fosterage to Snorri in preference to his two (legitimate) older brothers, Thord and Sigvat. Is it possible that he discerned signs of unusual precocity in a child so young? It is tempting to think so. But we may take it for granted that, with so wise and responsible a foster father, the child, and then the youth, early imbibed the respect for learning and culture prevailing at Oddi. And we may be certain that his knowledge of the law, his grasp of history, his profound insight into the nature of skaldship, were derived from instruction there.

When Jn Loptsson died (1197) Snorri, then about nineteen, seems to have continued living at Oddi. Snorris own father had died, and his widowfrom all we can infer, a gifted but extravagant womanhad run through Snorris share of his patrimony. To set the young man up in the world, a marriage was arranged for him with Herds, only child of Bersi the Wealthy; and when he died a few years later, Snorri moved with her to Bersis estate of Borg, which was also the ancestral home of Snorris family. Meanwhile Snorri had with all the impetuousness of youth plunged into the politics of his time and had quickly amassed a fortune, most likely in the same unscrupulous and ruthless manner he exhibited in his later dealings. With the inheritance from Bersi went the possession of a goor (gothi-dom), to which in the course of time others were added, so that Snorri soon became a powerful chieftain. The institution of the goi was peculiar to Iceland. It had come down from heathen timesChristianity had been adopted in 1000 A.D. by resolution of the Althingand survived till after the middle of the thirteenth century when it was superseded by royal subordinates. The goi (or temple priest) had both religious and secular prerogatives and duties. His office could be inherited or bought and sold or held in partnership, even loaned. The farmers and cotters of his bailiwick, known as his thingmen, had to pay toll to the temple and, later, to the church, and render the goi services. All their minor disputes were referred to him for settlement; and he on his part, like a feudal lord, afforded them protection.

In all likelihood Snorris marriage to Herds was only a cold-blooded means of acquiring wealth. In the year 1206 he left her in Borg, with what arrangements we know not. She had borne him a son and a daughter. He himself moved to the estate of Reykjarholt, some twenty-five miles to the east of Borg. He had acquired this property by an agreement with the priest Magns Plsson, who then put himself and his family under Snorris protection. Snorri is said to have been skilful in all he undertook. To this day one may see one of his improvements on this estate, a walled circular basin, some three feet deep and about twelve feet across, which is filled with water from one of the many hot springs in the Reykja Valley. No doubt it was originally roofed over so that it could be used at any time.

That Snorri as a comparatively young man was elected lawspeaker for the Althing, the yearly general assembly, bespeaks the respect of his peers for his ability. He occupied this responsible post during two periods, from 1215 to 1218 (when he went abroad), and then again from 1222 to 1231. As the laws were not written to begin with, the lawspeakers duties involved pronouncing the letter of the law in any case of doubt; and in Iceland, in particular, reciting the body of the law once a year before the assembled Althing. Needless to say, especially considering the inveterate propensity of Icelanders for litigation, an intimate knowledge of the law offered manifold opportunities for enriching ones self by taking advantage of the subtleties, the ambiguities, the dodges of the law. And Snorri seems to have made good use of this advantageand made many enemies thereby. The years while he lived at Reykjarholt were filled with feuding in which Snorri was by no means always the gainer.

Next page