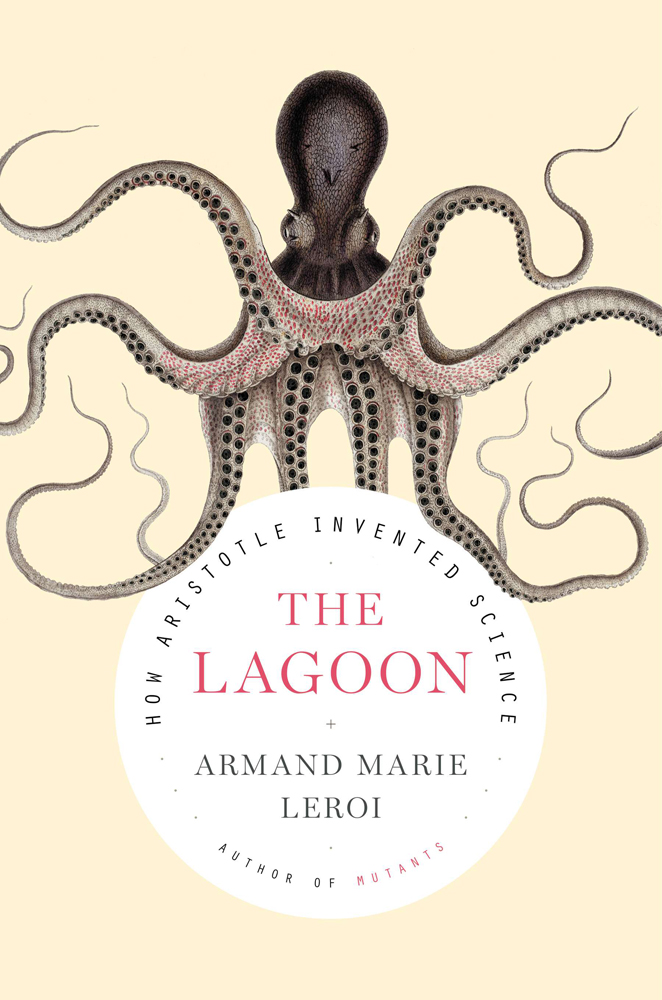

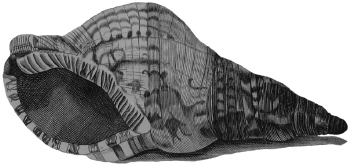

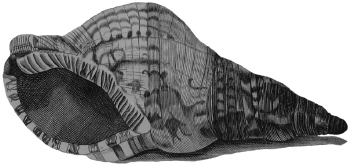

KRYX A TLANTIC TRUMPET C HARONIA VARIEGATA

I

T HERE IS A bookshop in old Athens. It is the loveliest I know. It lies in an alley near the Agora, next to a shop that sells canaries and quails from cages strung on the faade. Wide louvres admit shafts of light that fall upon Japanese woodblock prints propped on a painters easel. Beyond, in the gloom, there are crates of lithographs and piles of topographical maps. Terracotta tiles and plaster busts of ancient philosophers and playwrights do duty as bookends. The scent is of warm, old paper and Turkish tobacco. The stillness is disturbed only by the muted trills of the songbirds next door.

I have returned so often, and the scene is so constant, that it is hard to remember when, exactly, I first walked into George Papadatos bookshop. But I do recall that it was the drachmas last spring, when Greece was still poor and cheap and you landed at Ellinikon where the clacking flight boards listed Istanbul, Damascus, Beirut and Belgrade and you still felt as if youd travelled east. George lank grey hair, a bookmans paunch sat at his desk reading an old French political tract. Years ago, he told me, he had taught at Toronto But in Greece, they still had poets. He returned and named his store for the lyric muse.

Scanning his shelves, I saw Andrew Langs Odyssey and three volumes of Jowetts Plato. They were the sort of books that might have belonged to an Englishman, a schoolmaster perhaps, who had retired to Athens, lived on his pension, and died there with some epigram of Callimachus on his lips. Whoever he was, he also left, in a row of Clarendon blue, the complete Works of Aristotle Translated into English, edited by J. S. Smith and W. D. Ross and published between 1910 and 1952. Ancient philosophy had never held much interest for me; I am a scientist. But I was idling and in no hurry to leave the calm of the shop. Besides, the title of the fourth volume in the series had caught my eye: Historia animalium. I opened it and read about shells.

Again, in regard to the shells themselves, the testaceans present differences when compared to one another. Some are smooth-shelled, like the solen, the mussel and some clams, viz. those that are nicknamed milk-shells, while others are rough-shelled, such as the pool-oyster or edible oyster, the pinna and certain species of cockles, and the trumpet shells; and of these some are ribbed, such as the scallop and a certain kind of clam or cockle, and some are devoid of ribs, as the pinna and another species of clam.

The shell, for me it is always the shell, had sat in the sunlight of a bathroom windowsill, buried in sedimentary layers of my fathers shaving talc, seemingly for ever. My parents must have picked it up somewhere along the Italian littoral, though whether in Venice, Naples, Sorrento or Capri neither could recall. A summer souvenir, then, of when they were still young and newly married; but indifferent to such associations I coveted the thing for itself: the chocolate flames of its helical whorls, the deep orange of its mouth, the milk of its unreachable interior.

I can describe it so exactly for, although this was so many years ago, I have it before me now. It is a perfect specimen of Charonia variegata (Lamarck), the shell of Minoan frescos and Sandro Botticellis Venus and Mars. The trumpet of Aegean fishermen, weathered shells with a hole punched through the apex can still be found in Monastiraki stalls. Aristotle knew it as the kryx, which means herald.

It was the first of many: shells, apparently infinitely various, yet possessed of a deep formal order of shapes and colours and textures that could be endlessly rearranged in shoeboxes until finally, seeing that the mania would not cease, my father had a cabinet built to house them all. A drawer for the luminous cowries, another for the thrillingly venomous cones, one for the filigree-sculptured murexes, others for the olives, marginellas, whelks, conchs, tuns, littorines, nerites, turbans and limpets, several for the bivalves and two, my pride, for the African land snails, gigantic creatures that no more resemble a common garden snail than an elephant does a rabbit. What pure delight. My mothers heroic contribution was to type the catalogue and so become Conseil to my Aronnax, an expert in the Latinate hierarchy of Molluscan taxonomy, though her knowledge was entirely theoretical for she could scarcely tell one species from another.

At eighteen, convinced that my contribution to science would be vast malacological monographs that would be the last word for a hundred years (at least) on the Achatinidae of the African forests or, perhaps for my attention tended to wander the Buccindae of the Boreal Pacific, I went to learn marine biology at a research station perched on the edge of a small Canadian inlet. There, a marine ecologist, an awesome Blackbeard-like figure whose violent impatience was checked only by kindness to match, showed me how to peel away the layers of a gastropods tissues, more fragile than rice-paper, with forceps honed to a needle point and so reveal the severe functional logic that lies within. Another, a professorial cowboy-aesthete the combination seems incongruous yet he was utterly of a piece taught me how to think about evolution, which is to say about almost everything. I heard a legend speak, a scientist who had Laozis gaunt cheeks and wispy beard and who, blind from childhood, had discovered the one part of the empirical world that need not be seen and still can be known shell form, of course and had told its tales by touch alone. There was also a girl. She had wind-reddened skin and black hair and could pilot a RIB powered by twin Johnson 60s through two-metre surf and not flinch.