Jason A. Tipton Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Philosophical Biology in Aristotle's Parts of Animals 2014 10.1007/978-3-319-01421-0_1

Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014

1. Aristotles Philosophy and Biology: The Biological Phenomena

Abstract

What are we to do with the wealth of detailed information in the biological works of Aristotle? How easy is it to clearly distinguish between what some might describe as merely biological and the more philosophical, speculative discussions? Can the activity in which Aristotle is engaged be described as a philosophical biology? What would such an inquiry entail? This book aims to examine these questions through a detailed analysis of Aristotles Parts of Animals in conjunction with revisiting the detailed natural history observations made by Aristotle that inform, and in many ways penetrate, the philosophical argument.

In the scholarly works within the history and philosophy of biology, one does not often find data, illustrations or photographs of organisms. One can, say, certainly read the zoological works of Aristotle without reference to the parts or animate objects discussed in those writings. In the same way, one can read the Poetics without having read a particular tragedy under consideration. But I tend to want to have the biological phenomena in front of me when reading Aristotles Parts of Animals (HA) . For me, the phenomena add an element to the argument; perhaps I am convinced of Aristotles appeal to the Heraclitean idea that there are gods here too when exhorting his readers to look into what one might consider low and insignificant (645a5a35). Is there something divine about cephalopod mouths or fish tongues? While undoubtedly his exhortation is at least mildly hyperbolic, I am convinced by him to attempt to examine lowly organic forms in the hope that they help me better understand his thinking. DArcy Thompson, makes a more general claim when he suggests that Aristotle recognized the great problems of biology that are still ours to-day, problems of heredity, of sex, of nutrition and growth, of adaptation, of the struggle for existence, of the orderly sequence of Natures plan. Above all he was a student of Life itself. If he was a learned anatomist, a great student of the dead, still more was he a lover of the living. Evermore his world is in movement (Thompson 1913, p. 15).

1.1 The Biological Phenomena

In the introduction to his excellent commentary on the PA , James Lennox ( I aim to show that an interpretation of the PA can be both philosophical and scientific. The scientific aspects of the PA are one way into the philosophical aspects of the inquiry. Ultimately, I want to explore the possibility that what looks like parallel pathsone philosophical, one scientificcan be interwoven in a way that Aristotle seems to have intended.

The analysis of the philosophical argument of the PA will be enhanced by appealing to the actual organisms and traits that were of interest to Aristotle as a philosophical biologist. If one is suspicious about the veracity of certain of Aristotles observations, one might be suspicious of the philosophical argument. This might be what David Balme worries about when he claims:

Much of this criticism [of these biological writings] arose in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries from armchair naturalists who disbelieved Aristotles reports and thought them too silly for a great philosopherI confess that I was still blaming Aristotle for swallowing the story about buffaloes projecting their dung at enemies, until in 1983 I saw a picture on television of hippopotamuses doing just that. (, pp. 1617)

In a similar vein, Lennoxs (). This book will attempt to hold together what might look like, at first glance, the two aspects of the PA : our understanding is enhanced by a detailed analysis of the organisms and traits that consumed Aristotle; it is in this that the outlines of a philosophical biology begin to emerge.

The bulk of Aristotles work in natural history was done in the North Aegean, centered around Mitylini on the north Aegean island of Lesvos (Thompson ). It is generally acknowledged that Aristotle traveled to Lesvos with Theophrastus, who was from Eressos, shortly after Platos death.

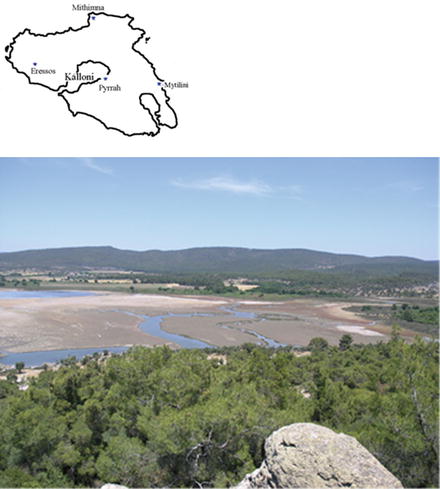

Fig. 1.1

DArcy Thompson (, p. 13) says that I take it then as probable, or even proven, that an important part of Aristotles work in natural history was done upon the Asiatic coast, and in and near to Mitylene. He will be a lucky naturalist who shall go some day and spend a quiet summer by that calm lagoon, find there all the natural wealth hosson Lesbos entos eeryei , and have around his feet the creatures that Aristotle loved and knew. Lesvos is a relatively large island (163,000 ha) in the Northern Aegean Sea. The Bay of Kalloni is a large (14,500 ha) body of water that roughly divides the island into two large lobes. A large marsh area ( below ) characterizes the head of the Bay near Pyrrah

I have spent 2 years in Lesvos, the location of much of Aristotles work in natural history, familiarizing myself with the creatures that Aristotle had at his finger-tips. I have done this while trying to keep an eye on the philosophical discussion of the PA .

Again, what does handling such things or even inspecting illustrations of such phenomena add to our understanding of the argument? At the very least, a photograph or illustration can bring to life what it is Aristotle is talking about. More significantly, seeing the phenomenon might allow one to better understand why Aristotle makes a certain argument or interpretation.

For example, do readers of Aristotle have in mind organisms like sea-squirts (ascidians) or sea cucumbers (holuthurians) when trying to understand Aristotles argument regarding plant-like animals (Figs. )? It has been my own experience that I understand the terms of the philosophical argument in a richer way if I have the phenomena in front of me. The discussion of plant-like animals is important in Aristotle because of the question about the continuum between plant and animal life. Where does Aristotle draw the line? Plant-like animals bring this question into focus and demonstrate the indeterminacy of any potential solution to the division.

Fig. 1.2

Ascidians or sea-squirts grow in potato-like clumps. These were collected in the Gulf of Gera, Lesvos. Ascidians are characterized by two orifices, inhalant and exhalant siphons ( arrows , upper right ). The difficulty in identifying one of the orifices as mouth and other as functioning for the sake of discharge is perplexing to Aristotle in examining these plant-like animals. However, the presence of these orifices allows Aristotle to suggest that ascidians are more animal-like in their nature than are sponges ( PA 681a10). On the other hand, the ascidians appear to have no residue, despite having an orifice that looks as if it is for waste disposal, which makes them plant-like ( PA 681a31). The second orifice is for the sake of discharging water ( HA 528a14). The ascidians are testaceans, or hard-shelled organisms. But unlike things like oysters, ascidians are enclosed in leathery husk ( HA 528a2). These animals, especially when handling them, do not immediately go together with the oysters. But, as Aristotle says, compared with one another testacea exhibit many differences, in respect both of their shells and their flesh within ( HA 528a5). The leathery husk has to be understood as a shell which completely envelops their flesh ( HA 528a21). The texture of the shell is between that of skin and shell (531a11)