PRAISE FOR

HOROLOGICON

Hard to put down... As engrossing for people interested in history and culture as it is for those who love words. Its the best word-themed book Ive read in years.

The New York Times Book Review

This is not a book to be gulped down at a sitting, but gently masticated to be savored in small bites... Every page contains a new jewel for logophiles and verbivores everywhere.

Publishers Weekly

[Horologicon] introduces readers to some of the best, weirdest, and most wonderful archaic terms... Forsyths fascinating entries employ erudite humor and playful historical anecdotes to make these dusty old words sound fresh again... Get ready to be impressed and entertained.

Library Journal

An entertaining trawl through the wonderfully colorful English vocabulary that has disappeared from daily use.

The Sunday Times (UK)

Characteristically brilliant.

The Daily Telegraph (London)

PRAISE FOR

ETYMOLOGICON

The Facebook of books... Before you know it, youve been reading for an hour.

The Chicago Tribune

A breezy, amusing stroll through the uncommon histories of some common English words... Snack-food style blends with health-food substance for a most satisfying meal.

Kirkus Reviews

The stocking filler of the season... How else to describe a book that explains the connection between Dom Perignon and Mein Kampf.

Robert McCrum, The Observer

Crikey... this is addictive!

The Times

Mark Forsyth is clearly a man who knows his onions.

Daily Telegraph

Witty and well researched... Who wouldnt want to read about the derivation of the word gormless? Or the relationship between the words buffalo and buff?

The Guardian (UK)

Books by Mark Forsyth

ETYMOLOGICON

HOROLOGICON

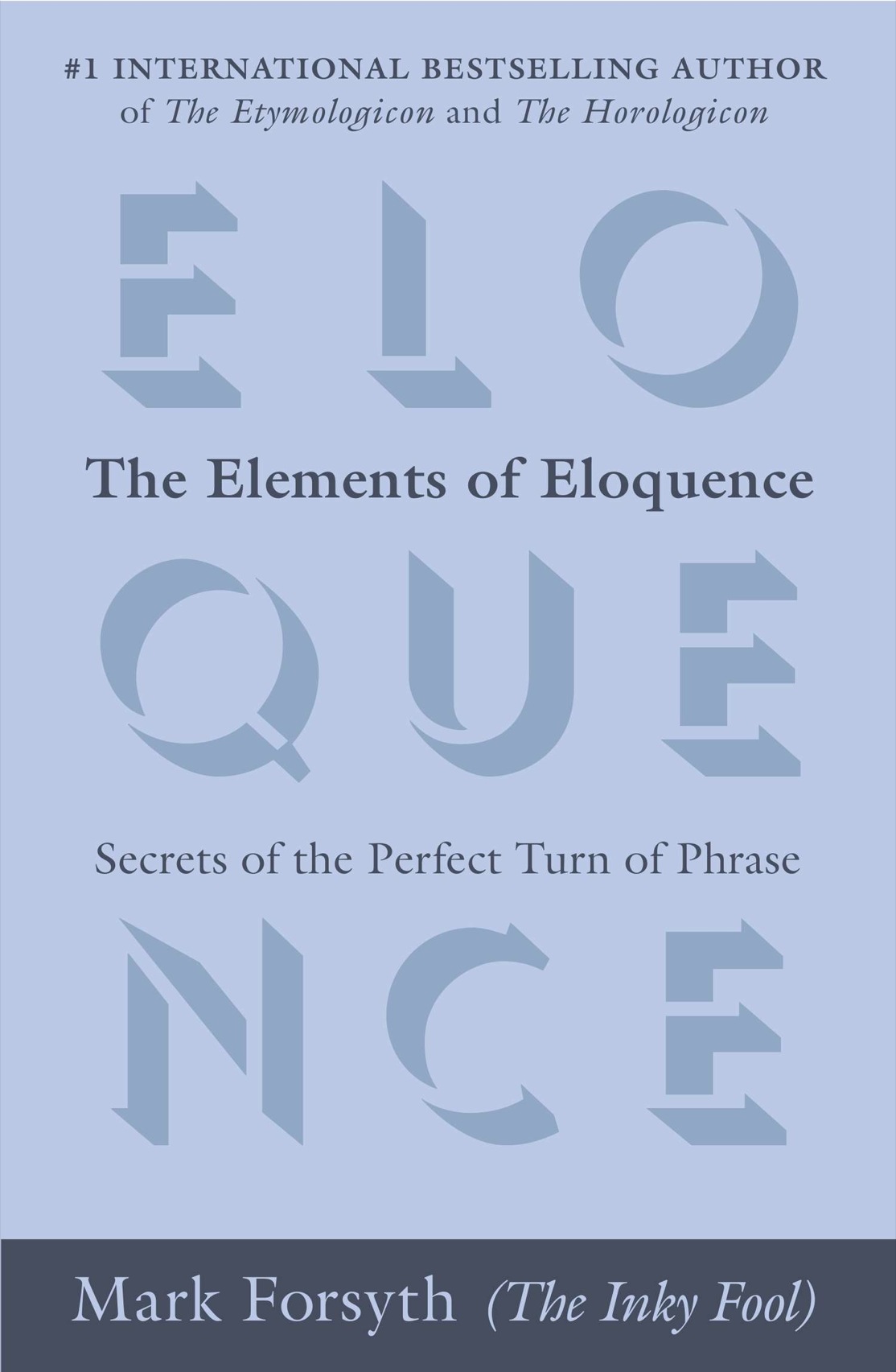

THE ELEMENTS OF ELOQUENCE

THE BERKLEY PUBLISHING GROUP

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

USA Canada UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

THE ELEMENTS OF ELOQUENCE

Copyright 2013 by Mark Forsyth

A continuation of this copyright page appears on page 239.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

BERKLEY is a registered trademark of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

The B design is a trademark of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

Berkley trade paperback ISBN: 978-0-425-27618-1

eBook ISBN: 978-0-698-16809-1

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Icon Books Ltd. hardcover edition / 2013

Berkley trade paperback edition / October 2014

Cover design by Danielle Abbiate

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make acknowledgment in future editions if notified.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

Does an explanation make it any less impressive?

WITTGENSTEIN,

REMARKS ON FRAZERS GOLDEN BOUGH

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to bow down in thanks and prose to Jane Seeber for her indefatigable aid.

For the last year, I have been unbearable company. My only question to friend or foe alike has been Can you think of any famous phrases that follow this particular structure? Many people have helped, but I cant exactly remember who. My thanks should probably go, in no particular order, to Jane Seeber, Andrea Coleman, Rob Colvile, Nick Popper, John Goldsmith, Michael Mellor, Hilary Scott, Adrian Hornsby, James Forsyth, Allegra Stratton, Alicia Roberts, Nick Roberts, my parents, Laura Humble, Simon Blake, Alister Whitford, Jeremy Large, Chris Mann, Claire Bodanis and anybody else whom I have rudely forgotten in my absence of mind.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

On Cooking Blindfolded

CHAPTER ONE

Alliteration

CHAPTER TWO

Polyptoton

CHAPTER THREE

Antithesis

CHAPTER FOUR

Merism

CHAPTER SEVEN

Aposiopesis

PREFACE

On Cooking Blindfolded

Shakespeare was not a genius. He was, without the distant shadow of a doubt, the most wonderful writer who ever breathed. But not a genius. No angels handed him his lines, no fairies proofread for him. Instead, he learnt techniques, he learnt tricks, and he learnt them well.

Genius, as we tend to talk about it today, is some sort of mysterious and combustible substance that burns brightly and burns out. Its the strange gift of poets and pop stars that allows them to produce one wonderful work in their early twenties and then nothing. It is mysterious. It is there. It is gone.

This is, if you think about it, a rather odd idea. Nobody would talk about a doctor or an accountant or a taxi driver who burnt out too fast. Too brilliant to live long. Pretty much everyone in every profession outside of professional athletics gets better as they go along, for the rather obvious reason that they learn and they practise. Why should writers be different?

Shakespeare wasnt different. Shakespeare got better and better and better, which was easy because he started badly, like most people starting a new job.

Nobody is quite sure which is Shakespeares first play, but the contenders are Loves Labours Lost, Titus Andronicus, and Henry VI Part 1. Do not, dear reader, worry if you have not read those plays. Almost nobody has, because, to be utterly frank, theyre not very good. To be precise about it, there isnt a single memorable line in any of them.

Now, for Shakespeare, that may seem rather astonishing. He was, after all, the master of the memorable line. But the first line of Shakespeare that almost anybody knows is in Henry VI Part 2, when one revolting peasant says to another: The first thing we do, lets kill all the lawyers. In Part 3 theres a couple moreI can smile, and murder while I smile. And each successive play has more and more and more great lines until you work up through Much Ado and Julius Caesar (1590s) to Hamlet and King Lear (1600s).

Shakespeare got better because he learnt. Now some people will tell you that great writing cannot be learnt. Such people should be hit repeatedly on the nose until they promise not to talk nonsense any more. Shakespeare was taught how to write. He was taught it at school. Composition (in Latin) was the main part of an Elizabethan education. And, importantly, you had to learn the figures of rhetoric.

Professionally, Shakespeare wrote in English. And for that he learnt and used the figures of rhetoric in English. This was easy, as Elizabethan London was crazy for rhetorical figures. A chap called George Puttenham had a bestseller in 1589 with his book on them (thats about the year of Shakespeares first play). And that was just following on from Henry Peachams