The author would like to thank Jane Seeber and Andrea Coleman for their judicious advice, sensible suggestions and peculiar patience.

This book is the papery child of the Inky Fool blog, which was started in 2009. Though almost all the material is new, some of it has been adapted from its computerised parent. The blog is available at http://blog.inkyfool.com/ which is a part of the grander whole www.inkyfool.com.

Therefore doth Job open his mouth in vain; he multiplieth words without knowledge.

Preambulation

Tennyson once wrote that:

Words, like Nature, half reveal

And half conceal the soul within.

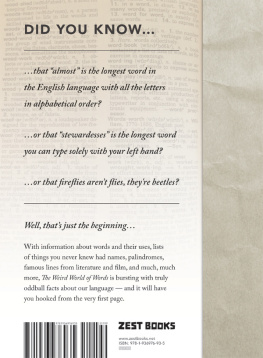

This book is firmly devoted to words of the latter half. It is for the words too beautiful to live long, too amusing to be taken seriously, too precise to become common, too vulgar to survive in polite society, or too poetic to thrive in this age of prose. They are a beautiful troupe hidden away in dusty dictionaries like A glossary of words used in the wapentakes of Manley and Corringham, Lincolnshire or the Descriptive Dictionary and Atlas of Sexology (a book that does actually contain maps). Of course, many of them are in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), but not on the fashionable pages. They are the lost words, the great secrets of old civilisations that can still be useful to us today.

There are two reasons that these words are scattered and lost like atmic fragments. First, as already observed, they tend to hide in rather strange places. But even if you settle down and read both volumes of the Dictionary of Obsolete and Provincial English cover to cover (as I, for some reason, have) you will come across the problem of arrangement, which is obstinately alphabetical.

The problem with the alphabet is that it bears no relation to anything at all, and when words are arranged alphabetically they are uselessly separated. In the OED, for example, aardvarks are 19 volumes away from the zoo, yachts are 18 volumes from the beach, and wine is 17 volumes from the nearest corkscrew. One cannot simply say to oneself, I wonder whether theres a word for that and turn to the dictionary. One chap did recently read the whole OED, but it took him a year, and if you tried that every time you were searching for the perfect word, you might return to find that the conversation had moved on.

The world is, I am told, speeding up. Everybody dashes around at a frightening pace, teleconferencing and speed-dating. They bounce around between meetings and brunches like so many coked-up pin-balls, and reading whole dictionaries is, for busy people like you, simply not feasible. Time is money, money is time, and these days nobody seems to have much of either.

Thus, as an honourable piece of public service, and as my own effort to revive the worlds flagging economy through increased lexical efficiency, I have put together a Book of Hours, or Horologicon. In medieval times there were books of hours all over the place. They were filled with prayers so that, at any time of day, the pious priest could whip out his horologicon, flip to the appropriate page and offer up an orison to St Pantouffle, or whoever happened to be holy at the time. Similarly, my hope with this book is that it will be used as a work of speedy reference. Whats the word? you will think to yourself. Then you will check your watch, pull this book from its holster, turn to the appropriate page and find ante-jentacular, gongoozler, bingo-mort, or whatever it might be. This is a book of the words appropriate to each hour of the day. Importantly, as I have noted, it is a reference work. You should on no account attempt to read it cover to cover. If you do, Hell itself will hold no horrors for you, and neither the author nor his parent company will accept liability for any suicides, gun rampages or crazed nudity that may result.

Of course, there is a slight problem with attempting to create an efficient reference work of this kind, namely that I have to know what you are doing at every moment of the day. This isnt quite as hard as it sounds. Ive consulted all of my friends and both of them have told me much the same story: they get up, they wash, they have breakfast and head off to work in an office. Neither of them is quite clear what they do there, but they insist that its important and involves meetings and phone calls, work-shy subordinates and unruly bosses. Then they pop to the shops, eat supper and, as often as not, head out for a drink. It is on this basis that I have made a game attempt at guessing your hypothetical life.

Some things I have, quite deliberately, ignored. For example, there are no children because they are much too unpredictable. I have included a chapter on courtship for reasons explained at the time. I havent quite been able to decide whether you are married sometimes you are and sometimes you arent although I am sure that you must possess a firmer opinion. Throughout, I have taken the liberty of imagining you as being half as lazy, dishonest and gluttonous as I am. You have to write about what you know. If you are a piece of virtue into whose wipe-clean mind sin and negligence have never entered, I apologise. This is not the book for you and I hope you have kept the receipt. And of course the nature of your job is a bit of a mystery and a sticking point.

Though most of this is being written in the British Library, as that is where the dictionaries are, the British Library is in fact very like an office, except that nobody is allowed to talk. It has all the usual usualnesses i.e. the lady on my left has spent the last hour on Facebook, occasionally chortling quietly and it has all the usual eccentricities i.e. the chap on my right has all sorts of behemothic tomes on the theories of post-Marxist historiography out on his desk, but is in fact reading Sharpes Revenge under the table, and thinks nobody has noticed.

I mean, I assume you work in an office, but I suppose I may be wrong. Though I have drawn on all the knowledge I could, I can never be quite sure that Ive got you down to a T. You might not work in an office at all. You might be a surgeon, or a pilot, or a cattle rustler, or an assassin, taking a little break between hits to find out the lost gems and hapax legomena of the English language before heading out for a hard days garrotting.

You could do anything, anything at all. Your life might be a constant welter of obscenity and strangeness. For all I know, you could spend all day inserting live eels into a horses bottom. If you do, I must apologise for the arrangement of this book, and the only consolation I can offer is that there is a single eighteenth-century English word for shoving live eels up a horses arse. Here is the definition given in Captain Groses