Copyright 2015 by Kevin Ashton

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Jacket illustration by Christoph Niemann

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ashton, Kevin.

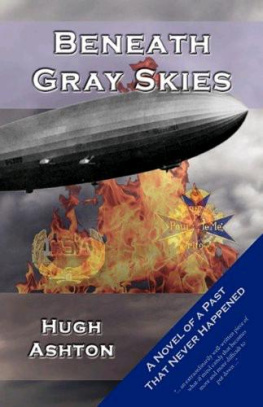

How to fly a horse : the secret history of creation, invention, and discovery / Kevin Ashton.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-385-53859-6 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-385-53860-2 (eBook)

1. Creative abilityHistory. 2. InventionsHistory.

3. Success History. I. Title.

B105.C74A84 2015

609 dc23

2014030841

v3.1

FOR SASHA, ARLO, AND THEO

A genius is the one most like himself.

THELONIOUS MONK

Work your best at being you. Thats where home is.

BILL MURRAY

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CREATING IS ORDINARY

CHAPTER 2

THINKING IS LIKE WALKING

CHAPTER 3

EXPECT ADVERSITY

CHAPTER 4

HOW WE SEE

CHAPTER 5

WHERE CREDIT IS DUE

CHAPTER 6

CHAINS OF CONSEQUENCE

CHAPTER 7

THE GAS IN YOUR TANK

CHAPTER 8

CREATING ORGANIZATIONS

CHAPTER 9

GOOD-BYE, GENIUS

PREFACE: THE MYTH

In 1815, Germanys General Music Journal published a letter in which Mozart described his creative process:

When I am, as it were, completely myself, entirely alone, and of good cheer; say traveling in a carriage, or walking after a good meal, or during the night when I cannot sleep; it is on such occasions that my ideas flow best and most abundantly. All this fires my soul, and provided I am not disturbed, my subject enlarges itself, becomes methodized and defined, and the whole, though it be long, stands almost finished and complete in my mind, so that I can survey it, like a fine picture or a beautiful statue, at a glance. Nor do I hear in my imagination the parts successively, but I hear them, as it were, all at once. When I proceed to write down my ideas the committing to paper is done quickly enough, for everything is, as I said before, already finished; and it rarely differs on paper from what it was in my imagination.

In other words, Mozarts greatest symphonies, concertos, and operas came to him complete when he was alone and in a good mood. He needed no tools to compose them. Once he had finished imagining his masterpieces, all he had to do was write them down.

This letter has been used to explain creation many times. Parts of it appear in The Mathematicians Mind, written by Jacques Hadamard in 1945, in Creativity: Selected Readings, edited by Philip Vernon in 1976, in Roger Penroses award-winning 1989 book, The Emperors New Mind, and it is alluded to in Jonah Lehrers 2012 bestseller Imagine. It influenced the poets Pushkin and Goethe and the playwright Peter Shaffer. Directly and indirectly, it helped shape common beliefs about creating.

But there is a problem. Mozart did not write this letter. It is a forgery. This was first shown in 1856 by Mozarts biographer Otto Jahn and has been confirmed by other scholars since.

Mozarts real lettersto his father, to his sister, and to othersreveal his true creative process. He was exceptionally talented, but he did not write by magic. He sketched his compositions, revised them, and sometimes got stuck. He could not work without a piano or harpsichord. He would set work aside and return to it later. He considered theory and craft while writing, and he thought a lot about rhythm, melody, and harmony. Even though his talent and a lifetime of practice made him fast and fluent, his work was exactly that: work. Masterpieces did not come to him complete in uninterrupted streams of imagination, nor without an instrument, nor did he write them down whole and unchanged. The letter is not only forged, it is false.

It lives on because it appeals to romantic prejudices about invention. There is a myth about how something new comes to be. Geniuses have dramatic moments of insight where great things and thoughts are born whole. Poems are written in dreams. Symphonies are composed complete. Science is accomplished with eureka shrieks. Businesses are built by magic touch. Something is not, then is. We do not see the road from nothing to new, and maybe we do not want to. Artistry must be misty magic, not sweat and grind. It dulls the luster to think that every elegant equation, beautiful painting, and brilliant machine is born of effort and error, the progeny of false starts and failures, and that each maker is as flawed, small, and mortal as the rest of us. It is seductive to conclude that great innovation is delivered to us by miracle via genius. And so the myth.

The myth has shaped how we think about creating for as long as creating has been thought about. In ancient civilizations, people believed that things could be discovered but not created. For them, everything had already been created; they shared the perspective of Carl Sagans joke on this topic: If you want to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe. In the Middle Ages, creation was possible but was reserved for divinity and those with divine inspiration. In the Renaissance, humans were finally thought capable of creation, but they had to be great menLeonardo, Michelangelo, Botticelli, and the like. As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, creating became a subject for philosophical, then psychological investigation. The question being investigated was How do the great men do it? and the answer had the residue of medieval divine intervention. A lot of the meat of the myth was added at this time, with the same few anecdotes about epiphanies and geniusincluding hoaxes like Mozarts letterbeing circulated and recirculated. In 1926, Alfred North Whitehead made a noun from a verb and gave the myth its name: creativity.

The creativity myth implies that few people can be creative, that any successful creator will experience dramatic flashes of insight, and that creating is more like magic than work. A rare few have what it takes, and for them it comes easy. Anybody elses creative efforts are doomed.

How to Fly a Horse is about why the myth is wrong.

I believed the myth until 1999. My early careerat London Universitys student newspaper, at a Bloomsbury noodle start-up called Wagamama, and at a soap and paper company called Procter & Gamblesuggested that I was not good at creating. I struggled to execute my ideas. When I tried, people got angry. When I succeeded, they forgot that the idea was mine. I read every book I could find about creation, and each one said the same thing: ideas come magically, people greet them warmly, and creators are winners. My ideas came gradually, people greeted them with heat instead of warmth, and I felt like a loser. My performance reviews were bad. I was always in danger of being fired. I could not understand why my creative experiences were not like the ones in the books.

It first occurred to me that the books might be wrong in 1997, when I was trying to solve an apparently boring problem that turned out to be interesting. I could not keep a popular shade of Procter & Gamble lipstick on store shelves. Half of all stores were out of stock at any given time. After much research, I discovered that the cause of the problem was insufficient information. The only way to see what was on a shelf at any moment was to go look. This was a fundamental limit of twentieth-century information technology. Almost all the data entered into computers in the 1900s came from people typing on keyboards or, sometimes, scanning bar codes. Store workers did not have time to stare at shelves all day, then enter data about what they saw, so every stores computer system was blind. Shopkeepers did not discover that my lipstick was out of stock; shoppers did. The shoppers shrugged and picked a different one, in which case I probably lost the sale, or they did not buy lipstick at all, in which case the store lost the sale, too. The missing lipstick was one of the worlds smallest problems, but it was a symptom of one of the worlds