THE LAST

QUEENS

OF

EGYPT

THE LAST

QUEENS

OF

EGYPT

SALLY-ANN ASHTON

First published 2003 by Pearson Education Limited

Published 2014 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2003, Taylor & Francis.

The right of Sally-Ann Ashton to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13: 978-0-582-77210-6 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book can be obtained from the Library of Congress

Set by Fakenham Photosetting Limited, Fakenham, Norfolk

CONTENTS

For Evelyn Foster Ashton

This book is intended for the general reader and, as a consequence, references have been kept to a minimum. However, a full source and reading list is provided at the back of the book and where comments or ideas are those of people other than the author their publications are mentioned in the text. It is also hoped that the book will serve as a general background introduction to undergraduate students who may be familiar with only one part of the Ptolemaic character and that it will provide a general introduction to aspects of Ptolemaic Egypt.

The reason for the paucity of publications on Egyptian queens when compared to kings is probably partly on account of the difficulty of finding relevant information. Personalities are virtually impossible to determine, the closest we can come is to consider the achievements of individuals and their presentation, which means that it is often necessary to rely heavily on archaeological evidence. Cleopatra and her ancestors often received bad press, usually at the hands of Roman authors and for this reason the present publication attempts to look beyond this bias in order to obtain a more rounded understanding of the role played by the Ptolemaic royal women.

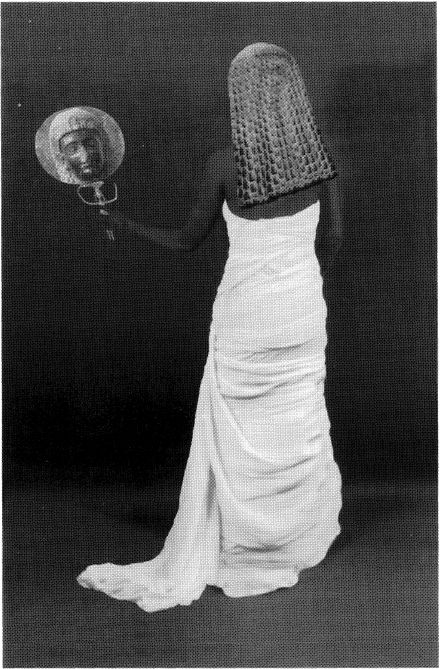

I would like to thank Frances Nutt for providing an inspirational image, illustrated in the Introduction. I am extremely grateful to Ian Blair, Lucilla Burn and Clare Pickersgill for patiently reading through the text and for their suggestions on the organisation of chapters; to Wolfram Grajetzki for sharing his thoughts on early dynastic queens and for his many other comments on the first draft of , and to Stephen Quirke for discussing several issues arising from this chapter. I would like to express a special thanks to Susan Walker for her advice on the structure and content of several chapters; the book is an easier read as a consequence. Any errors within the text remain my own.

I am extremely grateful to the following museums for permission to publish photographs of objects within their collections: the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (for their help in obtaining permissions: Mr Ahmed Abd el Fattah, Professor Mamdouh M. el Damaty, Ms Clare Derricks, Dr Morgens Jrgensen, Ms Ilse Jung, Mr Ivor Kerslake, Ms Sally Macdonald and Dr Mette Moltesen.

In some instances the publishers have been unable to trace the owners of copyright material, and would appreciate any information that would enable them to do so.

Finally I would like to thank Casey Mein of Pearson Education for suggesting this project and for her patience in seeing it through to fruition, and also my in-house editor, Melanie Carter.

Cleopatra VII is a major contender for the title of Egypts most famous queen; she and her ancestors were Macedonian Greek by descent and, as we shall see, maintained their links to the classical world, but they were also enthusiastic rulers of Egypt and supporters of Egyptian culture. There were in fact six queens with the name Cleopatra; confusingly, however, the best known is now distinguished from her predecessors by being identified as Cleopatra VII. Such mistakes are typical for a period that has caused confusion among modern scholars because of its dual persona. For those who take the time to consider the two faces of the Ptolemaic character, the reward is an insight not only into a complex but well-planned co-existence of two ancient cultures but, in terms of Egyptian history, also into profound developments in language, art and religion at a time that is often considered to be its twilight years.

This period saw an increase in the amount of power held by Egyptian royal women and developments in their political and religious roles. For the first time Egyptian artists, faced with the challenge of representing these modifications, developed new ways in which to represent the royal women. Some former queens of Egypt, however, had already enjoyed the powers invested in previous queens, as regents, goddesses and even pharaohs. This factor is important for our understanding of the promotion of the earliest Ptolemaic queens to a status beyond that ever seen in Greece, and is apparent in the developments of the Ptolemaic royal image from the third century BC.

Figure 1 (By Frances Nutt. Copyright and reproduced courtesy of Frances Nutt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London, UC 14521. The Greco-Roman Museum, Alexandria 3227.

In Greek history the death of Cleopatra VII marks the end of the Hellenistic age. This period began after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, when his vast kingdom was divided among his generals. It was a time when countries fell under the control and influence of Greeks and Greek rulers. It is also a time that saw an increase in the political role of women in the Greek world, and the Ptolemaic queens were without doubt the most prominent royal women of the Hellenistic period.

There is no one ancient image that is truly representative of the character of the Ptolemaic royal women, nor is there a representation that can allow us, as modern viewers, to share the impact that the appearance of the queens in Egypt in the fourth century BC would have made. As a modern audience we are as familiar with ancient Egyptian images as we are with those that were adopted and used in western art. How, then, can we understand the impact of the development of the presentation of the Ptolemaic queens, or how either Greek immigrant or native Egyptian reacted to these alien figures. The modern image illustrated in Figure 1 is probably the closest that the modern viewer can come to fully comprehending the way in which the queens presented themselves. It is a hybrid of styles and periods that together form the essence of what it was to be a queen in Ptolemaic Egypt. This image is particularly pertinent for the last queen of Egypt. Was she Macedonian or Egyptian? Both Greece and Egypt lay claim to her. Was she black? Was she beautiful? Did she really have such a large nose? It is difficult to imagine the same questions being asked of a king, and yet these are the types of question that are by far the greatest preoccupation with Cleopatra today. This book will not attempt to determine the physical appearance of the Ptolemaic royal women, because the stylised forms of image do not allow us to do so. What they do permit is a greater insight into 300 years of inspiration that influenced the last and most famous Ptolemaic queen