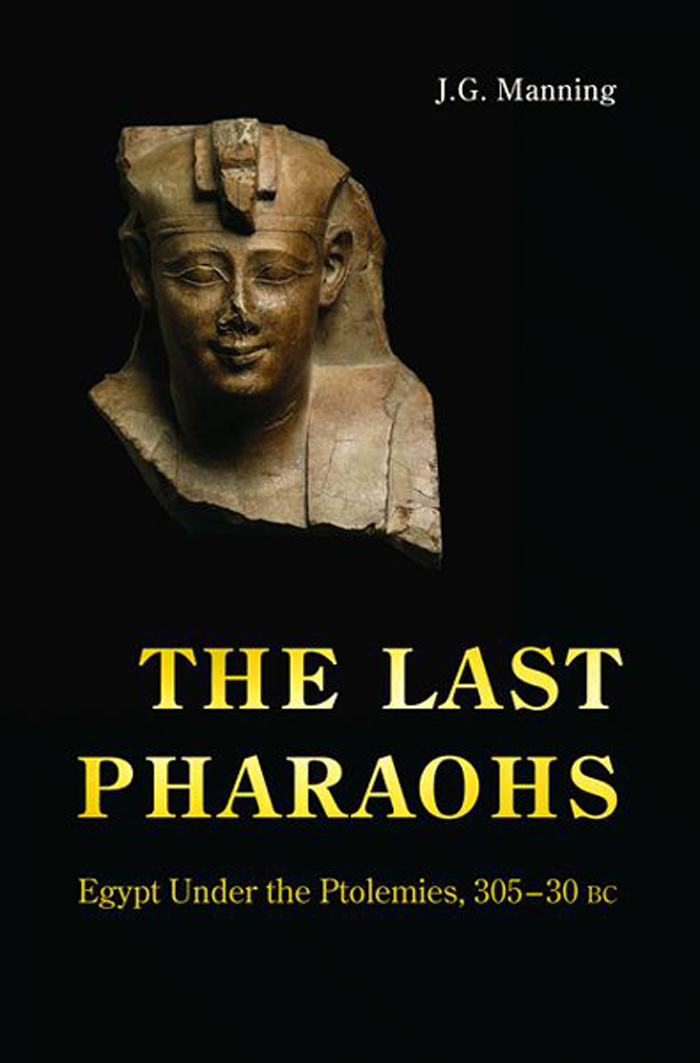

The Last Pharaohs

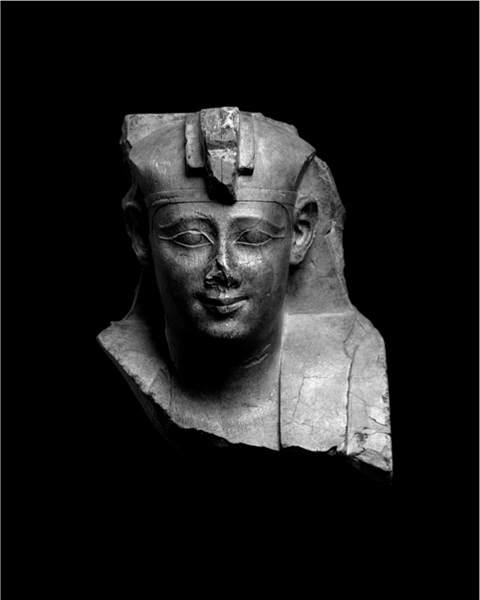

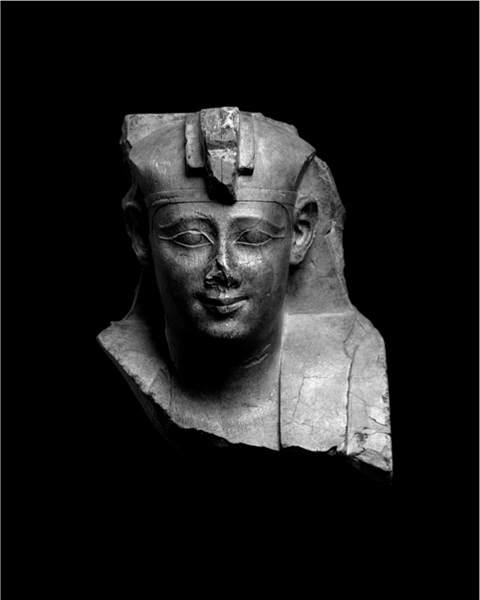

Bust of Ptolemy II, private collection.

The Last Pharaohs

E GYPT U NDER THE

P TOLEMIES , 30530 BC

J. G. Manning

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2010 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Manning, Joseph Gilbert.

The last pharaohs : Egypt under the Ptolemies, 305-30 BC / J.G. Manning.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-14262-3 (hbk. : alk. Paper) 1. Ptolemaic dynasty,

305-30 B.C. 2. PharaohsHistory. 3. State, TheHistory. 4. Egypt

Politics and government332 B.C.-30 B.C. 5. EgyptEconomic conditions

332 B.C.-640 A.D. I. Title.

DT92.M36 2009

932.021dc22 2009013223

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Naomi

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

FRONTISPIECE. Ptolemy II

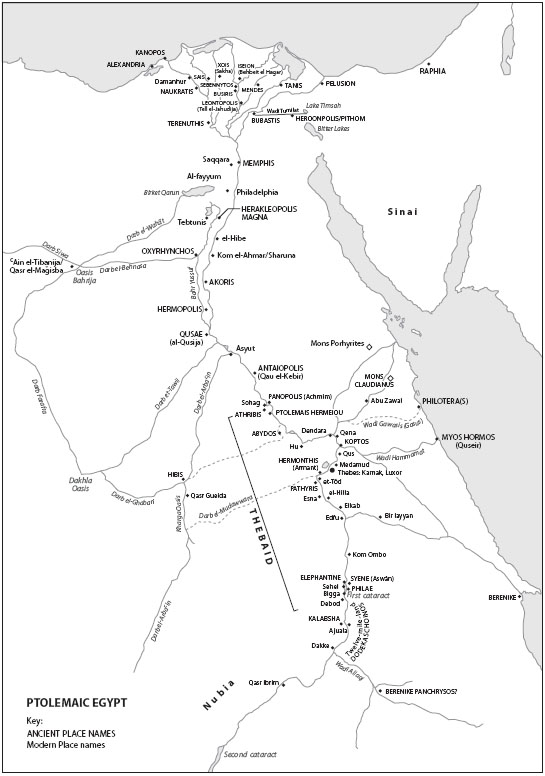

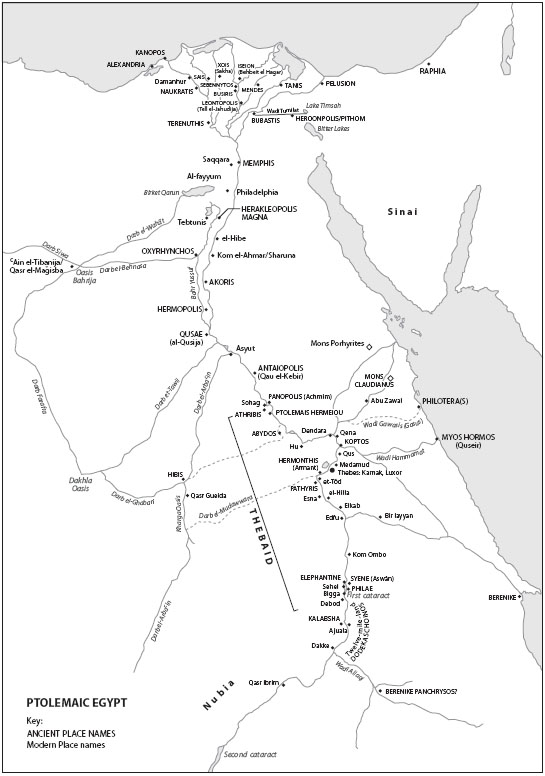

MAP OF EGYPT

PREFACE

This book attempts to draw a picture of Ptolemaic state making. My interest in the topic began many years ago when I began trying to understand how we might connect the rich and fascinating documentary material from the period to larger historical issues. Ptolemaic Egypt has for more than a century had a strong presence in academia and elsewhere, but it has often been isolated from other fields of ancient history. That isolation stems from a variety of causes. Ironically, the richness of the source material from the period has been one of the strongest of these. Scholars naturally want to specialize, and the material from Ptolemaic Egypt creates opportunities for many specialties indeed. But in the process the proverbial forest is often lost for the trees. A second, perhaps more vexing reason for Ptolemaic Egypts isolation from other scholarly fields is the prevailing understanding of Egypt as a place apart, so distinctive that its history has always followed a different course. According to this line of argument, Egypt has produced wonderful documents, but these can only be understood in Egypts own terms and are useful only for explaining its own history.

On the other hand, Ptolemaic Egypt has always had Kleopatra, and Alexandria, and both have shone in recent years. Kleopatra, the last of the last pharaohs of Egypt, has been the subject of several recent biographies, and a spectacular exhibition of her life and times has been presented in London and in my hometown of Chicago (Walker and Higgs 2001).

As for Alexandria, the great city has been virtually resurrected before our eyes in the last decade. Given the nature of its setting, much of ancient Alexandria will probably remain lost to us forever. But in the last few years, some exciting finds, including the probable discovery of the remains of the great lighthouse itself, have made it possible to match literary descriptions to some parts of the actual Ptolemaic city. The work of two French-led teams in the harbor of Alexandria and its environs has been particularly fruitful. Since the 1990s there has, in fact, been an up tick in archaeological activity throughout Egypt, unlike the other areas of the Hellenistic world. This has been especially true of survey and excavation work in the Fayyum, but there have also been good results in the western and eastern deserts. Roger Bagnalls summary (2001) will provide the reader with an excellent overview of this activity and its important contributions to the understanding of Ptolemaic and Egyptian history in general.

Other areas of research have further enriched our picture of Ptolemaic Egypt. Major studies of Ptolemaic coinage have been published recently (Duyrat 2005; von Reden 2007), and new assessments of Ptolemaic royal portraiture (Ashton 2001; Stanwick 2002) have deepened our understanding of the Ptolemaic period in its longer term historical context, giving us an Egyptological framework for understanding sculptures that have been predominantly viewed from a classicist perspective (Stanwick 2002:4). Many of the Egyptian temples of the period, our richest source for understanding ritual and ceremony, have received attention, and an important research project in Germany is overseeing the publication of the Edfu temple corpus. This project has brought us face to face with the world of Egyptian religious thought, and given us in some sense a glimpse of codified Egyptian culture as it was being shaped under Ptolemaic rule.

New texts have been published, and demotic Egyptian research tools are beginning, finally, to come up to the high standards set by Greek papyrology. As a result non-specialists now have access to these texts, which offers us fascinating insights into everyday family life, and of the lowest levels of the Ptolemaic administration. Demotic papyrology has in many ways revolutionized our views of Ptolemaic society, and ongoing efforts, especially on bilingual material, such as the superb work of Willy Clarysse and Dorothy Thompson on the Ptolemaic census, will continue to force revisions and refinements in our understanding of the Ptolemaic state. It is an exciting time to be a Ptolemaic historian.

Studies on many aspects of the period continue to appear at breakneck speed. I have not had the opportunity to include all of them in this book. Pfeiffer (2008) and Eckstein (2008) offer important insights into the dynastic cult and into international politics. Both of these studies offer important new ideas that shape our views of the Ptolemaic state, and I have as yet not been able to take full account of them.

Over the past five years I have presented papers in Berkeley, Copenhagen, Stanford, Tokyo, Philadelphia, New Haven, and Paris. The outcome of discussions stemming from these conferences is the basis of this book. I am particularly grateful to Zosia Archibald, Gene Cruz-Uribe, Vincent Gabrielsen, Peter Bang, John Davies, Todd Hickey, Graham Oliver, Bert Van der Spek, Walter Scheidel, Ian Morris, Christophe Chamley, Yoshiyuki Suto, Sugihiko Uchida, Franois Velde, Joachim Vogt, Josh Ober, Avner Greif, and Steve Haber who offered a good deal of conversation at these meetings, and elsewhere. They have helped to refine my very rough ideas. An earlier version of the section on coinage in chapter five appeared as Coinage as code in Ptolemaic Egypt in The Monetary Systems of the Greeks and Romans, ed. William Harris (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 84111. I am grateful to Professor Harris for including my work in that volume.

I am fortunate beyond description in having a superb circle of colleagues, many of whom also happen to be my friends. I have received criticism, comments, offprints and suggestions from most of them. Among them, I want to mention Roger Bagnall, Peter Bedford, Bart van Beek, Alan Bowman, Willy Clarysse, Mark Depauw, Steve Haber, Todd Hickey, Jim Keenan, Tomek Markiewicz, Cary Martin, Peter Nadig, Dominic Rathbone, Peter Raulwing, Jane Rowlandson, Dorothy Thompson, Katelijn Vandorpe, Arthur Verhoogt, Terry Wilfong. I also thank Professor Rein Taagepera for, on a moments notice, sending to me from Estonia a copy of one of his articles that I was having trouble locating. I am grateful to Steve Haber, Andrew Monson, Christelle Fischer, Cary Martin, and Uri Yiftach for reading parts of the manuscript, and for offering suggestions for improvement. Two readers for Princeton University Press offered many important suggestions for improvement and I am grateful to both of them. Great thanks are also due to Professor Todd Hickey and Mr. Geoffrey Metz, Curator of Egyptian antiquities, Uppsala University, for permission to publish the high-quality photographs of texts in this volume.