All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Founded in 1888, the National Geographic Society is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world. It reaches more than 285 million people worldwide each month through its official journal, N ATIONAL G EOGRAPHIC , and its four other magazines; the National Geographic Channel; television documentaries; radio programs; films; books; videos and DVDs; maps; and interactive media. National Geographic has funded more than 8,000 scientific research projects and supports an education program combating geographic illiteracy.

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463) or write to the following address:

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org

INTRODUCTION

LATE IN 1999 A YOUNG PALEONTOLOGIST , Tyler Lyson, was heading home after a day of fossil prospecting on his uncles land in the Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota. Water was running low, so it was time to head back home. As Tyler entered a small valley, bounded by a long, low butte on one side and a high domelike butte to the other, he noticed the telltale shapes that indicated a fossil bone.

Tyler had lived in North Dakota his entire life. Much of his childhood had been spent exploring the Badlands that surrounded and underpinned his hometown of Marmarth. From an early age he had shown a keen interest in the fossil remains littering the landscape where he and his brother often hunted for more modern prey. On his trips he was used to meeting a steady stream of academics that also hunted the Badlandsbut for an extinct variety of prey. Tyler was a sharp, intelligent young man who was hungry for knowledge and keen to learn. Most children have a period in their life when dinosaurs are a passion, but few can fuel their passion with vast quantities of fossil remains on their doorstep. Many visiting academics recall the incredible fossils that the young hunter had already plucked from the Badlands.

As Tyler crouched down to look at the find, he knew instantly he had found part of a dinosaur tail. This particular tale about a tail has a twist, given that these bones had weathered out of the stone where they had been lodged for more than 65 million years. Such exposure sometimes means theres more where that came from. A combination of searing summer heat, winter snows, and heavy rain not only sculpted the Badlands, but also has revealed many of the fossils entombed within the sediments.

Gravity is a useful tool for paleontologists in the field. Fossil bones do not roll uphill. So Tyler naturally examined the rock surface immediately above where the exposed tail vertebrae lay. His eye soon spotted the telltale sign of where the vertebrae had fallen from the rock. A patch of bone was still clinging to the rock face, waiting for the next heavy rain storm to reunite it with the bones at the bottom of the slope.

Tyler scrambled up the slope. Just like a layer cake, the sediments of a former floodplain in the Late Cretaceous Period had slowly built up over many years, creating the layers of Hell Creek Formation. As Tyler carefully dug around the tail vertebrae, he saw more buried beneath the surface.

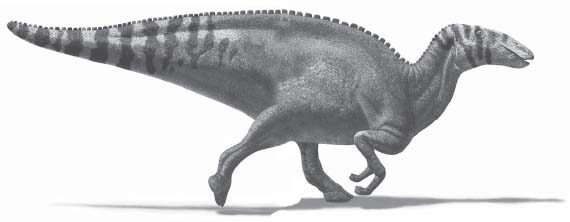

At that sight he hesitated. To start opening a new fossil site at the end of a field season is not a good idea. The problem of someone else discovering the site was not one of Tylers worries, since he was out in the back of beyond. His main concern was the coming winter. The heating, freezing, and washing with rainwater takes its toll on fossils that are exposed at the surface. Instead Tyler took out his notebook and GPS receiver to pinpoint the fossils position. In the same way a cars satellite navigation system can nail down where you are on Earth, these systems help us record the positions of paleontological sites so that we can relocate them with ease. Taking GPS coordinates for the site, he noted the location in his field notebook and carefully covered the bones. Tyler then packaged and labeled the bones that had already fallen from the site and brought his hand-sized parcel back to Marmarth. The shape of the bones told Tyler that he had found a dinosaur called a hadrosaurbut how much, he wondered, was buried back where hed been?

The answer was, incredibly: all of it. For the first time in history a dinosaur with all of its skin, except around a chest wound, would be unearthed. As readers familiar with seeing dinosaurs in museums are aware, the fossil record rarely preserves entire animals. Usually their deaths have left only tough fossil remains of shell, exoskeleton, and bone. From these remains paleontologists are tasked with charting the depths of the history of life on Earth. Yet in rare cases the creatures soft tissue has been preserved in stone. Such remarkable fossils enable immense advances in our understanding of long-vanished lives and forgotten worlds.

Dinosaur bones have fascinated human beings for thousands of years. Once upon a time such giant bones were reconstructed into the leviathans of myth and legend. They were not formally classified until the 19th century. Given that reconstructions are based upon the evidence available at a particular point in history, the restorations of dinosaurs have evolved through time. Until the mid-20th century dinosaurs were regarded as failures while we considered ourselves the ultimate expression of the success of life on Earth. The word dinosaur was at that time used to indicate cumbersome, outdated, doomed to fail, or unsuited to environment. Only since the 1970s have dinosaurs been rehabilitated, regaining their power to awe a popular audience.

Since the naming of the Hell Creek Formation 100 years ago, the fossil remains from the desolate Badlands have inspired generations of paleontologists to hunt for the elusive treasures of past life. These vast deposits contain some of the last fauna and flora from the age of the dinosaurs. Like many paleontologists before me, I, too, have been drawn to this fertile ground of T. rex and its kin. Five years would pass before Tyler returned to the hadrosaur site. Only then did he realize the unique potential of this fossil. This is when our paths first crossed and when we started on our exciting journey of discovery.

I am currently employed as a lecturer in paleontology in the School of Earth, Atmospheric, and Environmental Sciences at the University of Manchester in England and also as a Research Fellow at the Manchester Museum. For more than 20 years I have had the good fortune to concentrate much of my efforts on dinosaurs. The fossilized bones of the hadrosaur that Tyler had discovered would allow the resurrection of many grave secrets locked in stone for more than 65 million years. The presence of rare soft-tissue structures would ensure that this fossil would become a member of a prehistoric elitedinosaur mummies.