Ian MacAlister - Egypt: A History

Here you can read online Ian MacAlister - Egypt: A History full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: New Word City, Inc., genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Egypt: A History

- Author:

- Publisher:New Word City, Inc.

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Egypt: A History: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Egypt: A History" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

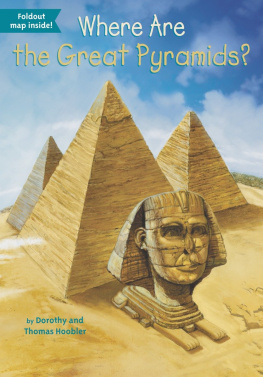

Here is the epic story of ancient Egypt and the pharaohs who made it great. Historian Ian MacAlister uses the pyramids and their mute, enigmatic sentinel, the Sphinx as the focal point for a sweeping yet human view of 3,000 years of Egyptian history.

Egypt: A History — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Egypt: A History" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

We owe the outburst of Egyptian civilization to a series of effective kings; we owe most of what we know of it to the tombs of these same kings. The pyramids and the lion-shaped sphinx that guards them are the visible tips of a society whose secular buildings - the cool, flimsy palaces where the king acted as judge, ordered expeditions to bring granite from Aswan or slaves from Nubia, ate, played draughts, listened to music, and made love - are like the hidden portions of an iceberg, submerged beyond recall in time and sediment. The world ruled by the sun-god Re is buried in the valley. The realm of death, associated with the western desert (beyond which the sun sank every evening), was under the sway of Osiris, father of Horus. His realm has left us more objects, great and small, than any other civilization of the past.

The profusion of Egyptian tombs and the wealth of their contents make it easy to picture the tomb builders as a nation in love with death; throughout the ages, mystagogues, necromancers, and false prophets have invoked the ancient Egyptians as their patrons. But what we know of them proves this picture inaccurate. In fact, they so loved the life that could be lived in their delectable valley that they wanted it to last forever. Their success at solving other problems, at keeping their enemies at bay, fostered a metaphysical self-confidence breathtaking in its audacity. They had tamed the ass to carry packs, and oxen to draw sleds and plows; their chisels had forced mountains to yield cut stone; their mattocks had begun to tame the banks of the Nile; their spells could even tame death.

This confidence took two different but related forms in the Egyptians long history. During the pyramid age, they believed that the king, who had been Horus in his lifetime, became Osiris after it; in some way, they partook of the immortality of their king. A millennium later, during the New Kingdom, Egyptian confidence advanced to a yet more ambitious plateau: every dead person became identified with Osiris, and so became an immortal god.

There was nothing democratic about the relationship between ruled and ruler in the Old Kingdom. No other society in recorded history has so exalted its monarch. In life, he was as far above ordinary mortals as the hawk that was his symbol. Palettes from predynastic times show these rulers to be pugnacious individuals, good at hunting and war. Throughout thirty dynasties and 3,000 years, the king would be depicted as in command, yet he was not a tyrant. As an incarnate deity, he upheld the fundamental order of the universe. His practical and spiritual power merited awe, homage, and tribute. The taxes paid in kind to the royal palace were tributes to a living god upon whose presence and vitality the crops themselves depended. Since the king was part of nature, he would naturally die; but like the dying crops or the setting sun, he would be born again, and everything could be reborn with him. According to French Egyptologist Alexandre Moret, a duty was thus imposed on ordinary men: It was necessary, and it was enough, that they help the gods to support even the test of daily, or periodic, death, and that they contribute, with all their efforts, to make them be reborn. The dead king was reborn as Osiris while a new Horus reigned on earth.

It is probable that in very early times a king who had reigned for thirty years was put to death and so was forced by his subjects into his new Osiris role. In historical times, a king who had completed thirty years of rule celebrated a jubilee, or Heb Sed, in which he symbolically became Osiris while still alive. That ceremony, which included a reenactment of the rulers coronation and a ritual run attesting his agility, helped him to revive his vital force - just as Osiris himself had been revived by the magic of Isis. These jubilees were often repeated at three-year intervals during the remainder of a monarchs reign. But however long preserved, the kings breath would fail at last. He would then take his place in the underworld, where even the sun-god spent half his time.

The prehistoric Egyptians may have believed in a bodily resurrection, but this notion was discarded early in dynastic times. Evidence of that shift can be found in the compilation of religious writings known as the Book of the Dead. The earliest version is inscribed on a pyramid built by Unas, ninth and last king of the Fifth Dynasty, Re receives you, the king is told, soul in heaven, body in earth. This view remained for 3,000 years. A text dating from a much later period repeats the message: Your soul is in heaven before Re; your double has what should be given to it with the gods; your spiritual body is glorious among the spirits of fire; and your material body is established in the grave.

The king in the grave remained a power in his own right. He thus differed from the hero of Greek history, whose memory deserved remembrance for his deeds. And he differed dramatically from the ancestors honored in other monarchies because of their blood connection with the living ruler. The king had become a god of the underworld who could affect life here and now. And since the underworld was the other half of a single, static reality, the dead king would, in that mirror world, have attributes and needs similar to those of the living. Just as he had developed a living form on earth, so there he would develop a spiritual form; just as his personality had grown in his living flesh, so his ka, or spiritual double, continued to develop in his corpse.

This process would take time, and the body needed to be preserved carefully from disturbance and decay. And the ka would need equivalents in death to what the king needed in life, from food and wine to ships and servants - even smaller, surrounding tombs for his advisers.

In life, the kings had no need for substantial buildings or solid luxury. Palaces of mud-brick, linen robes, and wooden beds sufficed for a living Horus in the dry, gentle climate. Reigns varied in length from a few days to the sixty-six years of Ramesses II. But a house for eternity - as Egyptians called the tomb - had to be far more durable than a palace. That it would cost much labor and stone to make it durable did not seem to matter. The royal tomb was not the preserve of an egoist displaying his wealth, nor a municipal monument; it was a place of immense importance to society. Its purpose, inside the framework of Egyptian assumptions, was as functional as that of a power station, and it was contrived with as practical ends in mind. The tomb was the place in which the dead king, securely buried, could receive homage and nourishment; from it, the king could make his successful journey to the afterworld and thence radiate blessings back to his people.

The tombs first function was, therefore, to act as a safe-deposit vault for a gold-lapped, gift-surrounded body - demanding the security that later civilizations would contrive for banks. The tombs second function was as the focus for a religious cult - requiring that it be as conspicuous and imposing as the places of pilgrimage and prayer in other religions. In short, an Old Kingdom tomb had to combine the functions of a great cathedral and Fort Knox. In the long run, the two functions were irreconcilable. For a dead body to be secure, it needed secrecy, not advertisement.

Significantly, the one Egyptian king whose body and treasures did survive almost intact to our own time was interred in an obscure corner of a hidden valley. The astonishing superstructures of the great tombs were like beckoning fingers to those ready to risk the hereafter and its possible pains for present gain - and every Egyptian generation would produce its quota of such sacrilegious thieves. But though the tomb builders rarely managed to outwit the persistent thief, they did succeed in constructing monuments whose grandeur impresses us to this day. In other responses to their funerary needs, they created art whose durability depended not on tons of stone but on beautys imperishable power.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Egypt: A History»

Look at similar books to Egypt: A History. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Egypt: A History and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.