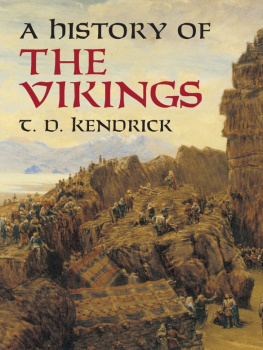

In the month of November 885, an immense fleet of 700 Viking vessels - one of the largest naval assemblages of the entire warrior age - sailed up the River Seine, penetrating into the very heart of France. At its head were Sigfred and Orm, two Viking chieftains who had been raiding in Frankish lands throughout the decade. On and on they led their fleet, and they pillaged as they went, until, on the twenty-sixth day of that bleak month, they were 100 miles inland and before the walls of Paris. The city was then concentrated on the boat-shaped Ile de la Cite in the middle of the river and already crowned with a cathedral and controlled the Seine and waterways beyond. From this all-important island city, two fortified bridges arched over the river. The Vikings could proceed no further without taking them.

The ruler of Paris, Charles the Fat, a great-grandson of Charlemagne and nominal head of the dwindled Frankish empire, was preoccupied elsewhere with fractious cousins trying to secede from the empire. All that remained to guard the bridges were 200 Parisian knights and their men-at-arms under Count Odo, marquis of the province of Neustria, and Bishop Joscelin, the citys ranking cleric.

Against this scanty defense, thousands upon thousands of ship-borne warriors hurled themselves into action. Horrible spectacle! exclaimed the monk Abbo, who witnessed the event from inside the precincts of the cathedral. In moments, the air was a blizzard of arrows. The stones of the fortress towers resounded with the clang of thousands of spears that were hurled against them. After the Vikings heaved flaming torches at the battlements, the whole city blazed with flames that, in Abbos words, painted the sky the color of copper.

Still, at days end, the ruined island city remained miraculously in the hands of its brave defenders. The Viking onslaught subsided - only to be renewed three days later. Then day after day, week after week, the Vikings pummeled Paris while Count Odo and Bishop Joscelin and their handful of stalwarts clung tenaciously to the walls of their city.

For all the ferocity of the attack, the Vikings did not succeed in taking Paris. But they did seize both banks of the river, and from there they held the city under siege for the better part of a year, simultaneously ravaging the French countryside for miles around. Not until late in 886 did Charles the Fat bring overdue assistance to the embattled Parisians, who by now were facing famine and pestilence. And then his action was that of a craven victim of blackmail. Instead of fighting off the Vikings, he granted them safe passage up the Seine, flouting the bravery of the Parisians - and, in addition, paid the warriors 700 pounds of silver to go and harass his rebellious subjects in Burgundy.

The long siege of Paris and its stunning aftermath exemplified how great Viking power and Viking ambitions had grown since the first few shiploads of warriors had descended howling upon Englands Lindisfarne monastery less than a century before. Those early summertime hit-and-run raids were the merest of larcenies compared with what the Norsemen learned to visit on the lands of northwestern Europe. As shrewd and pragmatic as they were violent, they soon saw the wasteful folly of returning home to Scandinavia, or even to the Shetland or Orkney Islands, after each raid. Instead, growing numbers of Vikings established quarters in easily defended islands in the mouths of the principal rivers that led inland from the sea, and they used them as bases for their murderous forays all year round.

Finding the land and the climate to their liking, these Vikings took to remaining as uninvited guests for longer and longer periods of time. And now in the last quarter of the ninth century, they swarmed out of their longships in ever-growing numbers, seeking not merely to loot but to conquer and carve out extensive territories to rule.

The mighty Viking invasions of France - and of England and Ireland as well - opened a new and fascinating chapter in the era of the Norsemen. The nature and history of the beset lands, the traditions and character of their peoples, and the strengths and weaknesses of the various Viking leaders made each of these three invasions markedly different from the others. And each produced a different - and sometimes surprising - result. In sum, they forever altered the course of medieval history.

Nowhere did the Vikings reach deeper, plunder with richer rewards, or settle more effectively than in the vast inchoate empire once ruled by Charlemagne. When Charlemagne died in 814, he left an enormous inheritance that reached from the Atlantic coast of France east to modern Hungary and from the North Sea south to the Mediterranean. All this went to his son Louis the Pious, so called for his ardent devotion to Christianity. In 823, Louis dispatched missionaries to Denmark in an early attempt to Christianize the pagan Vikings in their homeland. But he paid too little attention to the affairs of his earthly state - and to his own family. When he died, he left three quarrelsome sons - Charles the Bald, Louis the German, and Lothair, who for some reason seems to have escaped an epithet. These brothers went to war among themselves, which tore the empire asunder. Lothair retained the title of emperor and roughly the lands that are today Burgundy, Frisia, Lombardy, and Provence. Charles the Bald got the rest of what is now France while Louis the German got the lands roughly corresponding to modern Germany, which accounts for his name. And all three acquired packs of wolfish nobles as eager for plunder as the Vikings themselves. Naturally, the Vikings found this turbulent mass irresistible.

Typical of a number of brief alliances and rapid conquests made by the Norsemen was an incident that occurred in June of 842 along the River Loire, where an ambitious nobleman named Count Lambert was leading a rag-tag army in revolt against Charles the Bald. The count had been trying to capture Nantes - an old, Roman-walled city on the river - which would give him command of the province of Brittany. But his men could not breach the walls, and they had no way of attacking from the riverside - until the Vikings arrived in the area.

The Norsemen, in an expedition of sixty-seven longships, had sailed out into the Atlantic and down the west coast of France to the estuary of the Loire. There they stopped, confronted by a bewildering maze of shallow channels that meandered among brush-choked islands for a hundred miles upstream. They were apparently encamped, wondering what to do, when an emissary from Count Lambert arrived with a proposition. The count saw the Vikings as the answer to his prayers and offered to pilot them upstream to places of plunder in exchange for their help in capturing the city of Nantes. The Vikings, always keen to pounce upon any scheme that suited their purposes, readily agreed.

The date chosen for the combined attack was June 23 - and a shrewd option it was. June 23 was Saint Johns Eve, the shortest night of the year and one marked since prehistoric times in Europe by bonfires and fertility rites welcoming in the summer. For that reason, the people of Nantes would be too preoccupied with celebrating to notice what was happening on the river. The boats of the Vikings glided silently to a halt on the banks of the Loire at Nantes. There, with guttural roars now all too familiar along the coastlines of Europe, the warriors stormed into the merrymaking crowds, striking down people left and right and setting the tower afire.

Count Lambert, having wrested Nantes from Charles the Bald, then disappeared from history. Clearly, he gave the city no relief from the Vikings, who were to attack it in the future as they chose.

As for the immediate Vikings, after a few days they retired to the mouth of the Loire with all their booty. Then, instead of going home to Scandinavia, they settled on the large island of Noirmoutier just south of the Loire. From there, they scoured the countryside on both sides of the river, destroying towns, pirating merchant pack trains, and robbing farmers of their cattle and crops. The number of ships increases, the endless flood of Vikings never ceases to grow bigger, wrote the scholar Ermentarius about these years in the 840s. Everywhere Christs people are the victims of massacre, burning, and plunder. The Vikings overrun all that lies before them, and none can withstand them. They seize Bordeaux, Perigueux, Limoges, Angouleme, Toulouse. Angers, Tours, and Orleans are made deserts. Ships past counting voyage up the Seine, and throughout the entire region evil grows strong.

Next page