Alongside the brooding forested slopes of Trondheim Fjord in the year 998, King Olaf Tryggvason ordered the construction of what he intended to be the best and most costly ship ever made in Norway. She was called the Long Serpent, and the name was aptly chosen. This greatest of dragon ships was to extend more than 160 feet from her curved, monster-headed prow to her identically curved and serpentine tail. She was designed to hold thirty-four oars on each side, and she could carry hundreds of Vikings into battle. The bow and the stern were to be elaborately carved and gilded. The sails would be richly dyed, and brightly painted shields would hang on her sides.

Vast oak forests then covered much of southern Norway, but King Olafs men had to search far and wide to find a tree tall and straight enough to provide the trunk that would become the massive, 145-foot keel of this awesome ship. It took a small army of Viking shipwrights to procure the materials: splitting well-seasoned logs so that each plank was grained for maximum strength; searching out naturally formed oak and spruce elbows and arches for the ships ribs and struts; turning spruce roots into tough, naturally fibrous ropes to bind the shell and frame together; fashioning iron rivets and nails, wooden pegs or tree-nails, and walrus-hide thongs.

With all in readiness, construction began on the hull, starting from the great keel up. The task of carving the beautifully curved stempost and sternpost was entrusted to a skilled prowwright called Thorberg. Once these were in place, the planks would be added, each one placed above the last. But before the process of planking got under way, Thorberg was called back to his farm on urgent personal business. When he returned to the shipbuilding weeks later, he saw that the planking had been completed. To his dismay, he discovered that the journeymen carpenters - awed by the magnificent dragon ships size - had planked her with boards so thick that the ship would be much too heavy and clumsy in the water: The whole project would be a disaster.

King Olaf, unaware of this crucial flaw, was admiring the sleek, towering lines of the huge warship as she stood in the stocks. And everyone said that never was seen so large and so beautiful a ship of war. Thorberg said not a word. The next morning, the king came to take another look at his masterpiece and fell into one of the flaming rages for which he was so well known. During the night, someone had gone up and down one side of the ship, cutting deep notches in all the planks. The masterpiece was ruined, raged Olaf. The man shall die who has thus destroyed the vessel out of envy, he cried, and I shall bestow a great reward on whoever finds him out.

Then up spoke Thorberg, the prowwright: I will tell you, king, who did it. I did it myself.

You must restore it all, swore the king, to the same condition as before, or your life shall pay for it.

As the king stormed off, Thorberg picked up his axe and began chipping away at all the thick planks. He trimmed them down until their surfaces were even with the deepest of his notches. When King Olaf and his men came back and examined the shaved side of the ship, they were amazed and delighted.

As both Thorberg and Olaf well knew, the first principle of Viking ship building was lightness and flexibility. The thinner the planks, the lighter the boat; the lighter she was the less water she would draw so she could maneuver in shallow waters where heavier craft would most certainly run aground. Thinner planking also meant that a vessels sides could be built higher so that she could ride above taller seas - and so that Viking warriors aboard could hurl their spears down upon lower, more vulnerable vessels.

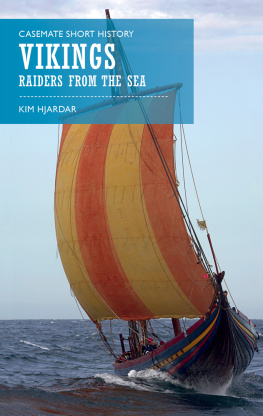

There were other advantages to thin planking. With a lightweight but durable shell, a Viking ship could flex in the ocean waves like a slim leaf. The keel could bend up and down by as much as an inch, and the gunwales could twist as much as six inches out of true without doing any damage to the ship. This would enable the hull to bend to the waves and slide through them with the least amount of resistance, making the ship faster and more stable. In the most favorable wind, a typical Viking ship could reach speeds of well over ten knots. And clearly, the Long Serpent could do even better.

For a man like King Olaf, who had led war bands most of his days, these were matters of life or death. He recognized the wisdom of Thorbergs alterations and ordered the prowwright to cut down the other side of the ship, too. He then appointed him master builder for the entire project. Ever afterward, Thorberg proudly bore the nickname Scafhogg, or Smoothing Stroke, and the mighty Long Serpent became the most famous dragon ship of all.

Living in the Sea

A terror to the outside world, the Viking longships - the biggest among them called dragons - were a source of justifiable pride to Norsemen. At a time when the majority of men and women in the West lived and died within walking distance of their birthplaces, when travel was slow and dangerous, Vikings seemed to skitter over the globe like water birds over a pond, appearing when they were least expected, disappearing when they chose. They could do this because, unlike the other peoples of Europe in the early Middle Ages, they understood the sea and the power that mastery of the sea could provide. Out of their primordial fjords and silent forests, endless waterways and wave-swept islands, they were born to the sea and were soon seaborne - amphibious by nature and destined to become the quintessential seafarers of their age.

The Danes, observed an early medieval chronicler, live in the sea. It was hardly an exaggeration, and it applied as well to the Swedes and the Norwegians. Long before they developed ships that were capable of traversing oceans, the Scandinavians depended upon the sea for food - fishing for cod, haddock, mackerel, sardine, tuna, and whiting. They ventured out ever farther from shore in their dugouts and skin boats and wooden craft of strange new shapes. And eventually dominance of the sea was theirs because of the sheer brilliance of their ship designs - and because of their ingenuity in devising different navigational methods.

The earliest Norse ships appear in rock carvings dating from about 1500 B.C. The usual high-curved stem and stern of Scandinavian double-enders are clearly visible in these carvings, the inevitable result of the Vikings having to negotiate the violent seas of the North. This form of double-ender, which was a uniquely Scandinavian design, permitted smooth handling of the ship even with a mountainous sea because the force of the waves was divided by the stern as easily as it was by the bow, and the stern then lifted - keeping the craft from being pooped and possibly overwhelmed.

Although some of the earliest Bronze Age boats in northernmost Scandinavia were sewn together from skins stretched over oak frames, another building technique appears to have been in use at the time in southern Norway. This was a peculiarly Norse creation, with the shell made not of skins but of thin wooden planks lashed together by withies - finely drawn, sinewy spruce roots. At first, this wooden boat was constructed with no keel, because the added strength provided by a keel was not necessary when the ship was just being rowed through the comparatively sheltered waterways and fjords, on the vast lakes, or through the endless archipelagoes of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. This lightweight craft could be beached easily, or she could be taken far up shallow rivers. Because of her high stem and stern, she could also venture out through the surf and across vast bodies of water, such as the Baltic or the Skagerrak during the better summer months. But for hundreds of years, she could go no further. The Norsemen had not yet devised sails, and about two days were as long as the weather was expected to remain calm enough for rowing.

Next page