The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

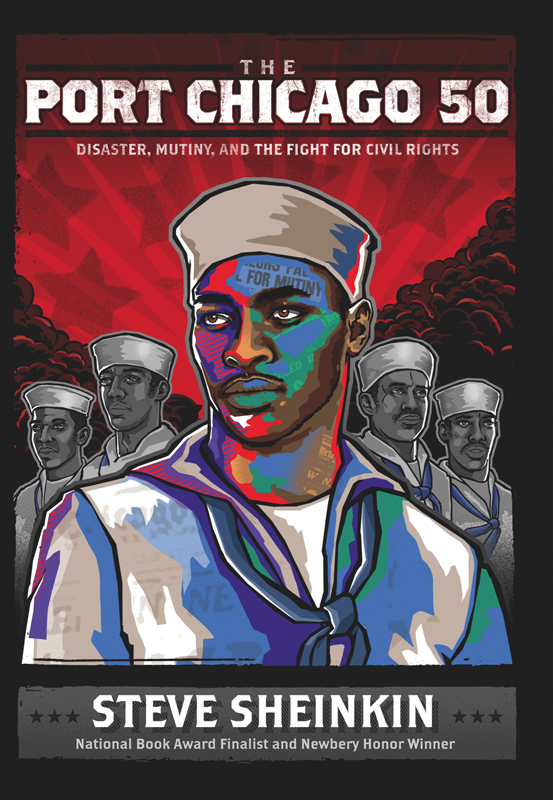

The Port Chicago 50

J ULIUS J. A LLEN

M ACK A NDERSON

D OUGLAS G. A NTHONY

W ILLIAM E. B ANKS

A RNETT B AUGH

M ORRIS B ERRY

M ARTIN A. B ORDENAVE

E RNEST D. B ROWN

R OBERT L. B URAGE

M ENTOR G. B URNS

Z ACK E. C REDLE

J ACK P. C RITTENDEN

H AYDEN R. C URD

C HARLES L. D AVID, J R.

B ENNON D EES

G EORGE W. D IAMOND

K ENNETH C. D IXON

J ULIUS D IXSON

J OHN H. D UNN

M ELVIN W. E LLIS

W ILLIAM F LEECE

J AMES F LOYD

E RNEST J. G AINES

J OHN L. G IPSON

C HARLES C. G RAY

O LLIE E. G REEN

H ARRY E. G RIMES

H ERBERT H AVIS

C HARLES N. H AZZARD

F RANK L. H ENRY

R ICHARD W. H ILL

T HEODORE K ING

P ERRY L. K NOX

W ILLIAM H. L OCK

E DWARD L. L ONGMIRE

M ILLER M ATTHEWS

A UGUSTUS P. M AYO

H OWARD M C G EE

L LOYD M C K INNEY

A LPHONSO M C P HERSON

F REDDIE M EEKS

C ECIL M ILLER

F LEETWOOD H. P OSTELL

E DWARD S AUNDERS

C YRIL O. S HEPPARD

J OSEPH R. S MALL

W ILLIE C. S UBER

E DWARD L. W ALDROP

C HARLES S. W IDEMON

A LBERT W ILLIAMS, J R.

At some time, every Negro in the armed services asks himself what he is getting for the supreme sacrifice he is called upon to make.

Pittsburgh Courier , November 9, 1944

FIRST HERO

HE WAS GATHERING dirty laundry when the bombs started falling.

It was early on the morning of December 7, 1941, at the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and Mess Attendant Dorie Miller had just gone on duty aboard the battleship USS West Virginia . A six-foot-three, 225-pound Texan, Miller was the ships heavyweight boxing champ. But his everyday duties were somewhat less challenging. As one of the ships African American mess attendants, he cooked and cleaned for the white sailors.

Miller was below deck, picking up clothes, when the first torpedo slammed into the side of the West Virginia . Sirens shrieked and a voice roared over the loudspeaker:

Japanese are attacking! All hands, General Quarters!

Miller ran to his assigned battle station, an ammunition magazineand saw it had already been blown apart.

He raced up to the deck and looked up at a bright blue sky streaked with enemy planes and falling bombs. Japans massive attack had taken the base by surprise, and thunderous explosions were rocking American ships all over the harbor. Two direct hits cracked through the deck of the West Virginia , sending flames and shrapnel flying.

Amid the smoke and chaos, an officer saw Miller and shouted for him to help move the wounded. Miller began lifting men, carrying them farther from the spreading fires.

Then he spotted a dead gunner beside an anti-aircraft machine gun. Hed never been instructed in the operation of this weapon. But hed seen it used. That was enough.

Jumping behind the gun, Miller tilted the barrel up and took aim at a Japanese plane. It wasnt hard, hed later say. I just pulled the trigger, and she worked fine.

As Miller blasted away, downing at least one enemy airplane, several more torpedoes blew gaping holes in the side of the West Virginia . The ship listed sharply to the left as it took on water.

The captain, who lay dying of a belly wound, ordered, Abandon ship!

Sailors started climbing over the edge of the ship, leaping into the water. Miller scrambled around the burning, tilting deck, helping wounded crewmembers escape the sinking ship before jumping to safety himself.

* * *

After the battle, an officer who had witnessed Millers bravery recommended him for the Navy Cross, the highest decoration given by the Navy. For distinguished devotion to duty, declared Millers official Navy Cross citation, extraordinary courage and disregard for his own personal safety during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor.

In early 1942, soon after the United States had entered World War II, Admiral Chester Nimitz personally pinned the medal to Millers chest. This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race, Nimitz declared. Im sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts.

Admiral Chester Nimitz pins the Navy Cross on Dorie Miller, May 27, 1942.

And then Dorie Miller, one of the first American heroes of World War II, went back to collecting laundry. He was still just a mess attendant.

It was the only position open to black men in the United States Navy.

THE POLICY

THE DAY AFTER JAPAN ATTACKED Pearl Harbor, the United States declared war on Japan. Japans powerful ally, Germany, responded by declaring war on the United States. World War II was already raging across Europe, Africa, and Asia. Now the United States had officially entered the biggest war in human history.

We are now fighting to maintain our right to live among our world neighbors in freedom, President Franklin D. Roosevelt told Americans in a radio address from the White House. We are now in the midst of a war, not for conquest, not for vengeance, but for a world in which this nation, and all that this nation represents, will be safe for our children.

Trucks with roof-mounted speakers cruised slowly through American cities, blaring the call to arms: Patriotic, red-blooded Americans! Join the Navy and help Uncle Sam hit back!

For black Americans this was not so simple. When they volunteered to fight as sailors, they were reminded of the Navys long-standing policy. They could serve on ships only as mess attendants.

* * *

It was a policy as old as the country itself.

When George Washington took command of the Continental Army in 1775, he told recruiters to stop signing up black soldiers. The fact is, black volunteers had already fought in the wars opening battles at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill. But slave owners objected that arming African Americans could lead to slave rebellions, and Washington agreed not to accept more black soldiers. Two years of losing battles to the British, and soldiers to desertion and disease, changed the commanders perspective. Washington needed men, no matter the color. Eventually, about 5,000 African Americans helped win the American Revolution.

Emanuel Leutzes 1851 painting, Washington Crossing the Delaware, accurately depicts a mixed-race regiment, with a black soldier rowing to Washingtons right.

The pattern was repeated soon after the Civil War erupted in 1861. At first the United States Army would not accept black men, fearing that to do so would offend the slave states that were still in the Union. Then, as the war dragged on, and the Unions need for fighting men grew increasingly desperate, the policy changed. More than 200,000 black soldiers fought to save the Union and end slaverybut they did so in segregated units, led by white officers.