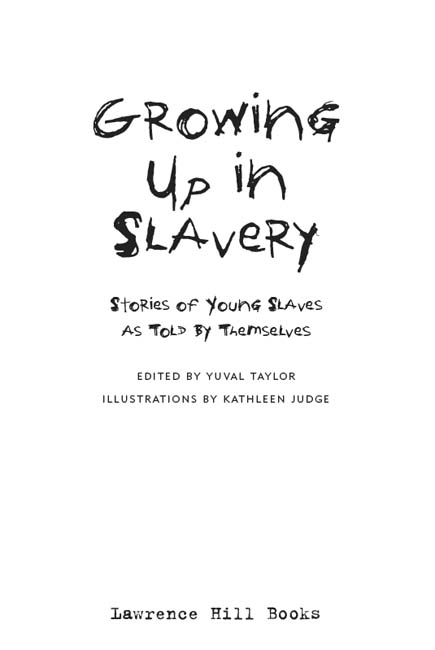

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Is available from the Library of Congress.

Cover and interior design: Joan Sommers Design

2005 by Yuval Taylor

Illustrations 2005 by Kathleen Judge

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Lawrence Hill Books

An imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 1-55652-548-6

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Pity me! You never knew what it is to be a slave; to be entirely unprotected by law or custom. You never exhausted your ingenuity in eluding the power of a hated tyrant; you never shuddered at the sound of his footsteps, and trembled within hearing of his voice.

H arriet Jacobs wrote those words shortly after she escaped to freedom, addressing the readers of her masterly and moving account of her slave experiences, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Like many other former slaves, Jacobs was burning with a desire to tell her story to as many people as possible: people who, while living in the same era as she did, were even more unfamiliar with the life of the slave than we are today.

In this book, ten slaves introduce to us, in their own words, their lives: what it was like to grow up enchained, robbed of their liberty and their very identity, forbidden even to read and write. They range from Olaudah Equiano, William Wells Brown, Frederick Douglass, and Elizabeth Keckley, who all became famous, to William H. Robinson, whose book has long been out of print and forgotten.

Each of these accounts, excerpted from their books, remains a singular story told in a singular voice. Each one shows a black youthall under the age of nineteentrying to come to terms with almost inconceivable circumstances: being torn from mother and family, not getting enough to eat, being constantly watched, being whipped and even tortured, being prey to their masters sadistic fancies. But these are not all tales of deprivation and violence. These slaves overcame tremendous obstacles to learn to read and write, and they tell how; they challenged authority in numerous ways, from trickery to outright rebellion; and they did the things that young people all do, from playing games to telling jokes to falling in love. And in telling their tales, they illuminate the unique conditions of slavery, from the passage in slave ships across the Atlantic, to daily life both on large plantations and in small city dwellings, to escaping slavery and even fighting in the Civil War.

Slavery in the United States affected millions of black Americans, often crushing them underfoot. But in the spirited accounts of these ten slaves, we see not only the horror and misery, but the vital human spirit that enabled them to survive.

INTRODUCTION

TRANSFORMING SLAVERY INTO LIBERATION

N o matter how many years may pass, the shame of slavery will color our countrys heritage. It was an established fact long before our birth as a nation; it caused our greatest war; it has shadowed every struggle, defeat, and victory of our land. Whites still apologize for it, blacks still resent it, and we are all oppressed by its legacy.

The slaves whose stories are collected here tried to lift the burden of that oppression. They transformed themselves from victims into agents of resistance just by telling their stories and protesting the vast injustice that was done to them. Along with other writers who had been slaves, they established a popular literary genre, sold hundreds of thousands of books, and advanced the antislavery cause. While they wrote mainly for their contemporaries, they produced works of lasting literary and historical value. In doing so, they performed an act of liberation.

This book presents the stories of ten slaves who wrote eloquently of their experiences as young men and women trapped in an intolerable situation. But these are only a small portion of a whole body of inventive, lucid, thoughtful, and passionate works of art: the literature of the slaves.

SLAVE NARRATIVES

Between the arrival of the first documented shipload of Africans in Virginia in 1619 and the death of the last former slave in the 1970s, some six thousand North American slaves told their own stories in writing or in written interviews. Most of these accounts are brief (many were included in periodicals, collections, or other books), but approximately 150 of them were separately published as books or pamphlets ranging from eight pages to two volumes. These accounts are commonly referred to as slave narratives.

At first, the slaves who wrote their stories seemed to think of their lives as adventures or spiritual journeys, instead of as tales of horror and abuse; in the titles of their books they called themselves Africans, not slaves. But beginning in 1824, with the publication of the Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave, the situation was reversed. Now the books were explicitly slaves stories, and almost always featured graphic scenes of cruelty. Over the years the books also became more like novelsthose published after 1852, the date of Harriet Beecher Stowes bestseller Uncle Toms Cabin, were far more likely to use re-created dialogue and other conventions of fiction.

Between 1836 and the end of the Civil War, slave narratives enjoyed great popularity, and over eighty were published. These narratives, which we may all call the classic or most typical narratives, share a number of similarities: most include a preface, written by someone else, describing the book as a plain, unvarnished tale; the first sentence of the book is usually I was born; the plot often includes a slave auction, the separation of the narrator from his family, an exceptionally strong and proud slave who refuses to be whipped, and at least two escapes, one of them successful.

The slave narratives published after the Civil War were not nearly as angry; they often ended with the narrator adjusting to newfound freedoms, rather than calling for them from exile; and certain aspects of slave life began to seem quaint or colorful rather than horrifying. Now, instead of trying to convince their readers that slavery was evil, these writers were trying to present a balanced picture of their lives. The emphasis on freedom in the classic narratives was replaced by an emphasis on progress.

The slave narratives, with very few exceptions, were all written or dictated by former slaves. In the history of slavery in the United States, probably between 1 and 2 percent of the slave population managed to escape. The young men and women who wrote or told their stories were therefore more courageous, hardy, resourceful, or imaginative than those who were left behind. Most of them hailed from near the Mason-Dixon line (which separated the slave states from the free). They often knew how to read and write, even though that was forbidden by law; a large number had served as house slaves and had thereby learned something of the outside world by watching their masters; most had excellent memories and were extraordinarily intelligent. Also, quite a few of the narrators were of mixed race, or mulatto. While mulattoes constituted only between 7 and 12 percent of the slave population, they were not only more likely to be house slaves, but it was easier for them to pass as white when escaping. The age at which they wrote their tales varied from their early twenties to their mid-seventies, and between 10 and 12 percent of them were women.

Next page