Also by YUVAL TAYLOR

Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in

Popular Music (with Hugh Barker)

Growing Up in Slavery: Stories of

Young Slaves as Told by Themselves (editor)

The Cartoon Music Book (editor, with Daniel Goldmark)

The Future of Jazz (editor)

I Was Born a Slave: An Anthology of

Classic Slave Narratives (editor)

Also by JAKE AUSTEN

Flying Saucers Rock n Roll: Conversations with

Unjustly Obscure Rock n Soul Eccentrics (editor)

TV-a-Go-Go: Rock on TV from American

Bandstand to American Idol

A Friendly Game of Poker: 52 Takes on the

Neighborhood Game (editor)

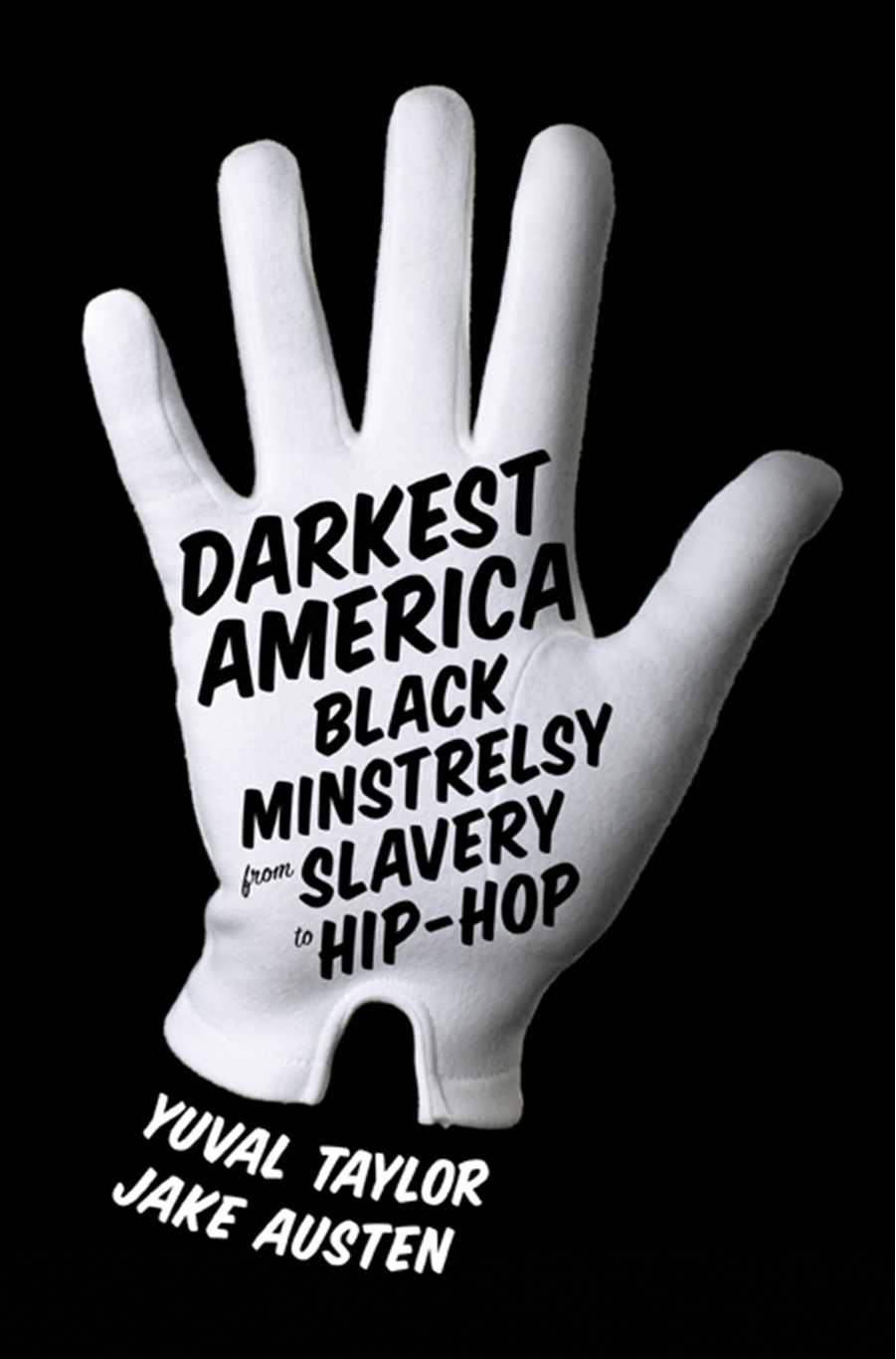

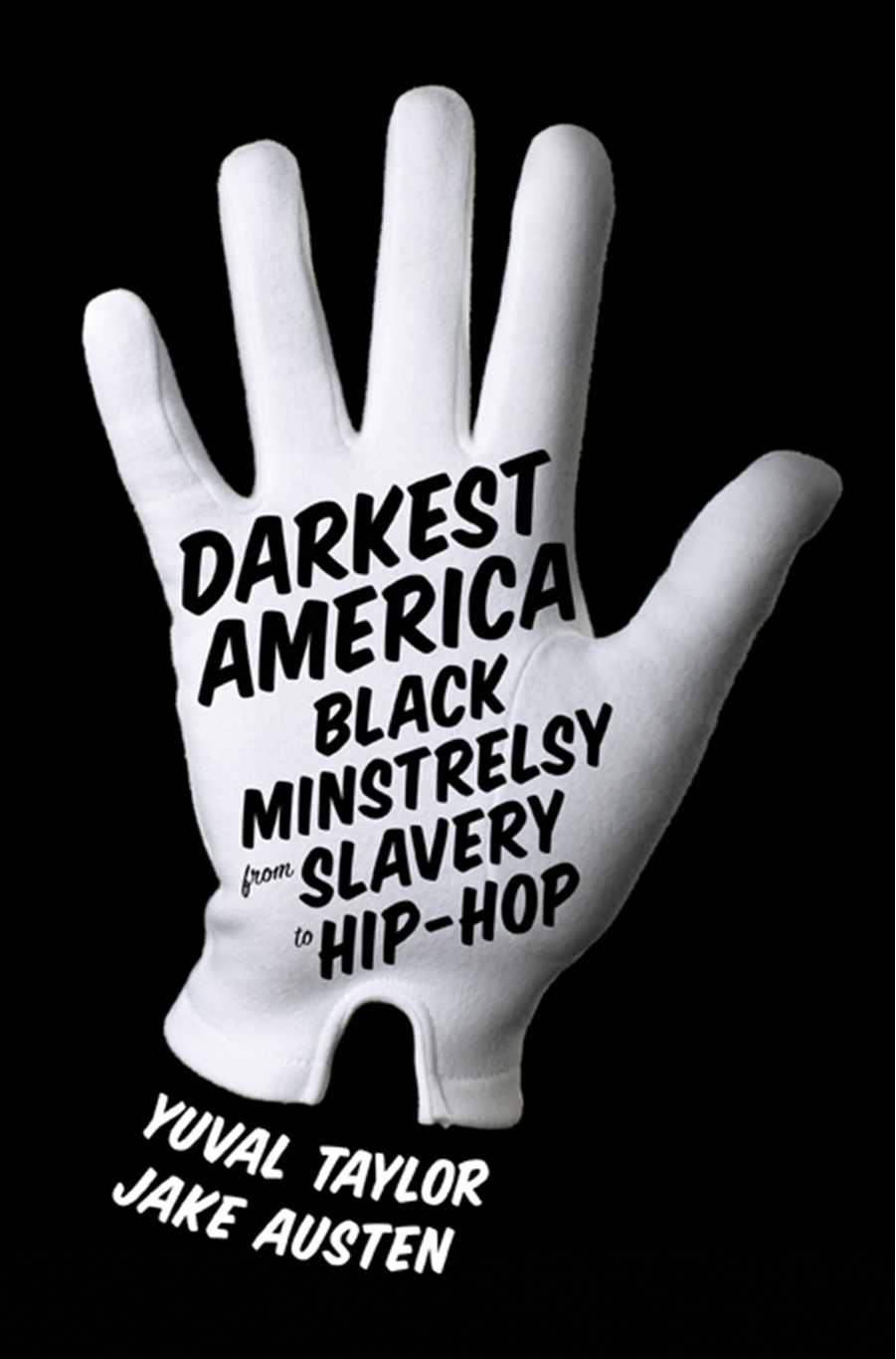

DARKEST

AMERICA

BLACK MINSTRELSY FROM

SLAVERY TO HIP-HOP

YUVAL TAYLOR and JAKE AUSTEN

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Dedicated to our families

for all their support

Heres when blackface is OK...

when you have a black face!

L ARRY W ILMORE ,

The Daily Show, 2009

Contents

How New Orleanss Zulu Krewe Survived

One Hundred Years of Blackface

Andy, and Company Brought Black Minstrelsy to

the Twentieth-Century Screen

How Black Popular Singers Kept Minstrelsys

Musical Legacy Alive

How Zora Neale Hurston Let Her

Black Minstrel Roots Show

How Spike Lee and Tyler Perry Brought

the Black Minstrelsy Debate to the

Twenty-First Century

FOREWORD BY MEL WATKINS

B OTH LITERALLY AND FIGURATIVELY , minstrelsy cast a grotesque, if strangely conflicted, shadow over the American landscape. From its inception in the 1840s, when it quickly emerged as the nations most popular entertainment form, until at least the turn of the twentieth century, traditional minstrelsy principally thrived by presenting variety shows featuring burlesqued depictions of African Americans. Black minstrelsy, authors Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen write, is based precisely on the adoption of the most slanderous fictions that white people have used to characterize black men.

White and, later, black entertainers corked up, donning absurdly exaggerated, often hideous blackface makeup to create a visual image of the comic Stage Negro; ill-fitting clothing, malaprops, nonsensical chatter, a slavering addiction to watermelons and chicken, a shuffling gait and/or contrasting propensity to break into frenzied dance or flight when in earshot of syncopated music or eyesight of a cemetery were added to complete the picture. By the end of the 1800s this wildly overdrawn, Sambo-like figure was a ubiquitous presence in American culture. Frequently advertised as a true reflection of the character and culture of former black slaves, it was accepted as such by a vast number of Americans.

Formal minstrelsy would gradually disappear, but the stereotypical Negro caricature that it helped etch into the nations psyche lingered and continued to resurface on- and offstage through the 1960s civil rights movement and even into the twenty-first century. During this time, the authors suggest, black Americans have reacted to the caricatures in three distinct ways: by embracing them, signifying on them, or attacking and refuting them.

The niggling truth about stereotypes and caricatures, of course, is that within their excesses and distortions a shred of reality is nearly always present. And, indeed, close scrutiny reveals that faint traces of authentic African American rural folk culture are to be found even in minstrelsys Sambo characterization. This presence explains why historians and social critics such as Mark Twain, Constance Rourke, and Eric Lott have argued that minstrelsy should be partly credited with bringing aspects of black folkways and folk art to mainstream Americas popular culture. It may also partially explain two of the problematic issues engaged by Darkest America authors Taylor and Austen: why some African American entertainers willingly incorporate aspects of the stereotype into their acts and why so many members of the black community still embrace the seemingly slanderous stereotypes and find them humorous.

These are among the fundamental questions this work sets out to answer. The motivation for writing this book is to explore black minstrelsys artists, art, and audience reactions, the authors write, the ways the innovative performances of the minstrel stage have affected the subsequent century of African American performance, performances that have consistently defined American popular culture.

Toward that goal, Taylor and Austen have assembled a survey and selective examination of African American culture from the nineteenth century to the present. Beginning with such blackface entertainers as William Henry Juba Lane, Billy Kersands, and Bert Williams, the narrative traces the influence of minstrelsy on African American performance for over a century, concluding with an analysis of works by such present-day artists as Dave Chappelle, Flavor Flav, Lil Wayne, Spike Lee, and Tyler Perry.

Examples are drawn from various media, including the stage, radio, music and song, motion pictures, and television. The authors dutifully examine such familiar hot-button phenomena as the Amos n Andy show (in both its radio and TV manifestations) and Stepin Fetchit, reaffirming the performers apparent debts to minstrelsy, and analyze the frequently voiced assertion that much rap music and performance is little more than blackface revisited. But this work is most distinguished and enlivened by its surprising turns (a reinterpretation of Bert Williamss work that takes issue with conclusions drawn by his biographers, for instance) and unexpected subjects such as a firsthand report on the Zulu Krewe, a black group that has marched in New Orleanss Mardi Gras parade wearing blackface for more than a hundred years.

There are also fresh assays and interpretations of artists who have rarely been associated with the minstrel tradition that will likely inspire heated debate and/or dissent. Paul Robeson and Ray Charles, for example, are cited along with the black vaudeville stars Ernest Hogan (who wrote All Coons Look Alike) and James Bland (who vied with Stephen Foster in penning sentimental odes to plantation life) as having clearly reflected the minstrelsy revival in some of their music.

Darkest America is finally a richly detailed examination of the effect that comic minstrel caricatures have had on African American performers and audiences. The inherent difficulty of the task is evidenced in the last chapter, which is focused on Spike Lees film Bamboozled (described as a bold, angry, vehement damnation of black minstrelsy) and the rift between Lee and director Tyler Perry (who seemingly enthusiastically embraces many minstrelsy-inspired comic tropes). As the authors conclude, definitive answers to questions concerning the acceptance or rejection of contemporary expressions of minstrelsy-inspired comedy are not easily acquired. Intense scrutiny, they suggest, may muddy the waters rather than clarify thema consequence that is partially derived from the inherently contradictory nature of humor. As Langston Hughes once observed, comedy is often what you wish in your secret heart were not funny. But it is, and you must laugh.

Clearly, however, Darkest America is a valuable contribution to the growing body of research on minstrelsy and its long-lasting effect on American culture. Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen should be commended for this probing examination of one of the nations most influential cultural phenomena.

New York City, January 2012

Mel Watkins is the author of On the Real Side: A History of African American Comedy .

Next page