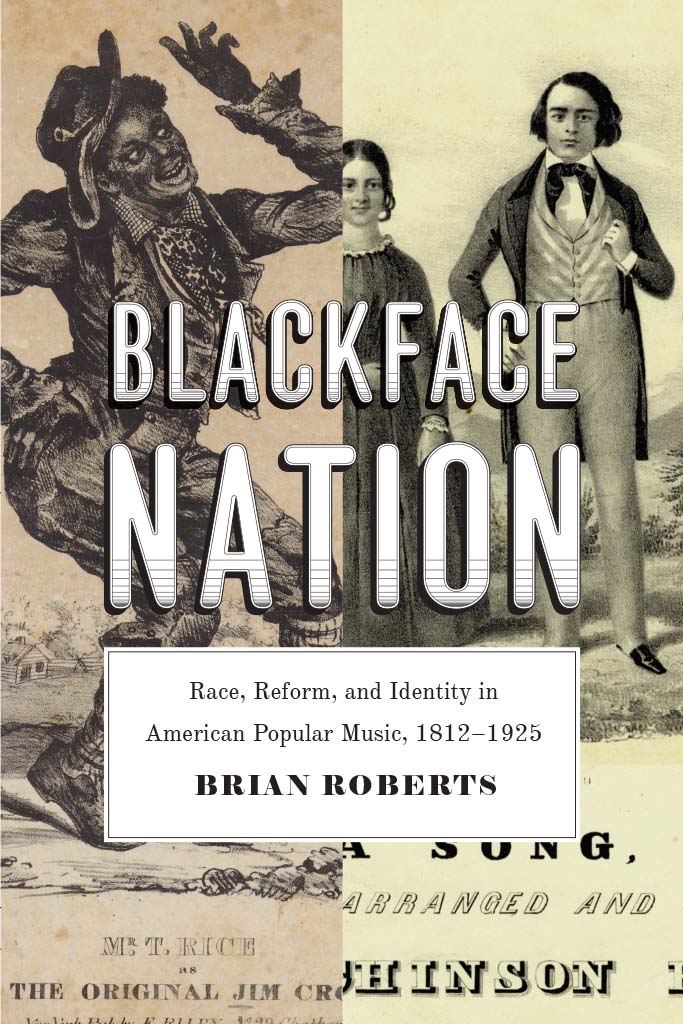

Blackface Nation

Blackface Nation

Race, Reform, and Identity in American Popular Music, 18121925

BRIAN ROBERTS

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-45150-3 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-45164-0 (paper)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-45178-7 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226451787.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Roberts, Brian, 1957 author.

Title: Blackface nation : race, reform, and identity in American popular music, 18121925 / Brian Roberts.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016041541 | ISBN 9780226451503 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226451640 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226451787 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansMusicHistory and criticism. | Popular musicUnited States19th centuryHistory and criticism. | Popular musicUnited States20th centuryHistory and criticism. | Minstrel musicUnited StatesHistory and criticism. | Music and raceUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC ML 3479. R 63 2017 | DDC 781.64089/96073dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016041541

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

To Barbara

From northern peaks to prairie wastelands to academic forests prime-evil,

my partner on the trail of life.

Contents

Someone once told me that writing a second book would be easier than writing a first. That may be true for most people. Indeed, it seems many academics can get started on their research sometime midmorning, wrap up data collection by noon, and whip out the book in time for a quiet aperitif with friends. It has never worked this way for me.

This project started a long time ago, so long ago that many of the people I have to thank are retired. By retired, I mean dead. Or maybe they are living out in the woods someplace. Im pretty sure they will not remember me. First there is the staff from the American Antiquarian Societythe staff, that is, from way back in 1999. The AAS got me started on this monster by granting me a yearlong residency, a fellowship supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Charlotte Newcombe Foundation. While I was at the AAS, I benefited enormously from research suggestions and source-finding aid from Gigi Barnhill, Joanne Chaison, Tom Knoles, Marie Lamoureux, Sara Hagenbuch, and Laura Wasowicz. The legendary Caroline Sloat kept me on track and helped me make the transition from doing research on music to writing history. More recently at the AAS, Jacklyn Penny and Lauren Hewes provided much-needed assistance with illustrations.

I also need to thank the staff at the Lynn [Massachusetts] Historical Society; Wadleigh Library in Milford, New Hampshire; the Milford Historical Society; the G. W. Blunt Library at Mystic Seaport Museum; the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts; the Haverhill [Massachusetts] Public Library Special Collections; the New Hampshire State Archives; and the New Hampshire Historical Society.

I benefited from several grants from my home institutions. Back when this research was a pile of notes, California State UniversitySacramento gave me a couple semesters of reduced course load. They probably expected this book to be the result of the largesse, about fifteen years ago. More recently, but still back when few people carried phones, the University of Northern Iowa granted me a Summer Research Fellowship and a Professional Development Assignment, a summer of supported research, and a one-semester leave to write. I researched and wrote all I could but was still ten years away from getting it done. Over the years, I had a few graduate assistants at UNI who went out and retrieved sources: Patrick Parker, Tasha Fristo, Ray Werner, and Mindy Stump. My undergraduates were helpful in ways they probably never realized, for I tried out many of my craziest ideas on them.

Tim Mennel, my editor at the University of Chicago Press, has been all that a great editor can be, doling out equal parts comfort, hectoring threats, praise, whip-crackings, and pep talks. He guided this book through some stormy seas and helped me identify all the leaky places for patchwork and re-timbering. I also need to thank the presss excellent readers for giving so much of their time to the manuscript. All were indispensable in forcing me to clarify my thinking and hone my arguments. As with all readers reports, I have come to appreciate them more as I look back on the experience of revisions. Finally, Marianne Tatoms copyediting helped me avoid a numberless array of wording issues and punctuation pitfalls. Any remaining errors are mine.

In the end, I have to say that writing this book was a pretty solitary experience. I needed two dogs to get through it: my beautiful Bolivian mountain dog Geraldine (aka Jelly) and the crazy border collie Moss (aka Mossy Glen of Randolph). The vast majority of help came from one source and one colleague. This was of course Barbara Cutter. She listened to me talk about this book, ad nauseam, Im sure; she dealt with my flights of fancy, my sense of discovery, my fevers of purchase when we found ourselves in the music sections of local historical society gift shops. She kept me going; and there were times when I really, really felt like giving up. She even listened to quite a bit of the music I refer to here, including not only reenactments of the Hutchinson Family Singers and the Virginia Minstrels but the weird stuff: sea chanteys, ballads about false young rakes, the Nightmares. I can truly say this book would have been impossible without her.

It was the dawn of a new millennium, and according to their cherished ideal of progress, Americans should have been leaving the old modes of expression behind. Yet there it was: in the fall of 2001, several all-white fraternities at major universities decided the best way to celebrate Halloween was by holding blackface parties.

The idea was not original. According to a spokesperson with the Southern Poverty Law Center, such festivities were on the rise, having become a more regular occurrence than we would like to think. At the end of October, the brothers held their parties: drinks were drunk, fun was had, and mistakes were made. They had a good time, so good they had to post the party pictures to a social media site. This was one of the evenings mistakes. Offended visitors to the site forwarded the images to officials at the students schools and on to civil rights organizations. The parties became the incidents.

What did the pictures show? Most, it seems, featured young white males in blackface make-up, decked out in backwards ball caps, afro wigs, fake gold jewelry, and T-shirts emblazoned with Greek letters. A typical example centers on two jaunty junior-achiever types. Their darkened faces do little to mask their identities; they are clearly white, privileged, middle-class college kids. Yet they have adopted poses in self-conscious rebellion against this identity, making gang-related hand gestures while sneering good-naturedly at the camera. Their shirts, innocent enough at first glance, are marked with the letters of one of the schools black fraternities.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).