.

7.1 Romance

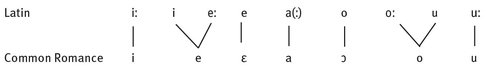

The following discussion of the relevant developments of Romance languages on the way from Latin is based on Loporcaro (2011). Remarkably, as he notes, none of the descendants of Latin has preserved the quantity distinctions present in the Latin vocalic system. The collapse of the length contrast, however, had very different results in different dialects. In Sardinia, the short and long counterparts simply merged, yielding a simple and symmetrical five vowel system out of the symmetrical ten vowel system of Latin. In Daco-Romance (including French), the merger in the front region was the same as that in Daco-Romance, and the entire pattern was symmetrical in that the merger in the back vowels mirrored that in the front vowels. Consequently, the short high vowel /u/ merged with the long mid vowel  , and not simply with its long counterpart, that is .

, and not simply with its long counterpart, that is .  These somehow unexpected developments, in the front vowels of Daco-Romance and both back and front vowels of common Romance, are explained by the laxness of short vowels and tenseness of long vowels already in Latin. And so it is stipulated that short /i/ was phonetically /I/, and short /u/ was phonetically

These somehow unexpected developments, in the front vowels of Daco-Romance and both back and front vowels of common Romance, are explained by the laxness of short vowels and tenseness of long vowels already in Latin. And so it is stipulated that short /i/ was phonetically /I/, and short /u/ was phonetically  , which brought their qualities closer to those of long tense

, which brought their qualities closer to those of long tense  and

and  , and not of their original counterparts, i.e.

, and not of their original counterparts, i.e.  and

and  . Loporcaro argues that the qualitative re-organization of common Romance was not simultaneous with the loss of quantitative contrasts, but that the latter were brought about by Open Syllable Lengthening. In effect, the following correspondences () between Latin and common Romance can be observed.

. Loporcaro argues that the qualitative re-organization of common Romance was not simultaneous with the loss of quantitative contrasts, but that the latter were brought about by Open Syllable Lengthening. In effect, the following correspondences () between Latin and common Romance can be observed.

: Latin and common Romance vocalic systems (after Loporcaro 2011: 115)

Notably, the vowel system eventually lost contrastive vowel length, but gained an additional vowel height. A number of vocalic changes followed in descendant languages, including a context-free vowel shift in Castilian.

A major difference between the situation in Romance and in English is that the length contrast, while eventually abandoned altogether in Romance, did not disappear from English, but was replaced by another contrast, namely by a phonological tense/lax contrast. While the ten phoneme vowel system of Latin was reduced to seven phonemes in common Romance, the early Modern English vowel system, where the duration-based length contrast came to be replaced by a quality-based tense/lax contrast, was still twenty vowels strong, which is only two vowels fewer than the Middle English system and four vowels fewer than the classical Old English system. Although a detailed analysis of any one lineage of Romance cannot be conducted here, it seems that indeed the number of context-free vocalic changes relative to other kinds of changes would remain lower than the relevant number traced in this thesis for English. Even though the collapse of the length contrast did arguably set in motion a number of vowel changes in Romance, this has not reached the scale found in English. Potential reasons for this difference are: (a) a lower number of vowel phonemes to begin with, (b) a greater number of monosyllables in English, (c) movable stress, that is the placement of stress on various syllables of the same root under the influence of a stress-moving suffix in Romance. As for (a), the number of phonemes was not found to correlate with the rate of change in English, and so it does not seem to be a likely candidate responsible here. Still, it cannot be excluded that the number of distinct vowel phonemes plays a role, since the number is higher throughout the history of English, so it might be a prerequisite, which, when joined by other relevant ingredients, results in vowel shifts. As for (b), the increased number of monosyllables in English was said to result from fixed lexical stress, and the accumulating prominence of stressed vowels at the cost of the erosion of prominence of unstressed vowels (as prominence of one element is always relative to some other element). Consequently, the number of monosyllables is unlikely to be an independent factor. As a result, (c) that is the properties of stress placement in the varieties of, or one lineage of, Romance would have to be investigated more closely to find parallels to, or interesting differences from, English.

Icelandic

Another development in another language with some relevance to the scenario sketched here for English is the loss of quantity-based distinctions in Icelandic. In Modern Icelandic, vowel length is predictable from the context, and so it does not mark lexical contrasts. Despite the minority view of rnason (2011), who has recently suggested that vowel quantity is (re-)emerging as distinctive in Icelandic, most traditional accounts (e.g. Haugen 1958; Anderson 1969; Gussmann 2002), or, in Gussmanns (2009: 49) words practically everybody working in the area of Icelandic phonetics and phonology assumes non-contrastiveness of vowel length. Now, the vocalic system of Old Icelandic (rinsson 1994) was radically different, in that it was a nearly perfectly symmetrical one, where eight short vowels had their long contrastive counterparts.. The development with relevance to this book is the loss of distinctive vowel length on the way from Old Icelandic to Modern Icelandic. The customary division between Old and Modern Icelandic is the year 1540, the year of the publication of the first Icelandic translation of the New Testament. The knowledge of the phonology of Old Icelandic stems from the descriptions found in the First Grammatical Treatise, written in the twelfth century. The relevant changes are sketched below.

, and not simply with its long counterpart, that is .

, and not simply with its long counterpart, that is .  These somehow unexpected developments, in the front vowels of Daco-Romance and both back and front vowels of common Romance, are explained by the laxness of short vowels and tenseness of long vowels already in Latin. And so it is stipulated that short /i/ was phonetically /I/, and short /u/ was phonetically

These somehow unexpected developments, in the front vowels of Daco-Romance and both back and front vowels of common Romance, are explained by the laxness of short vowels and tenseness of long vowels already in Latin. And so it is stipulated that short /i/ was phonetically /I/, and short /u/ was phonetically  , which brought their qualities closer to those of long tense

, which brought their qualities closer to those of long tense  and

and  , and not of their original counterparts, i.e.

, and not of their original counterparts, i.e.  and

and  . Loporcaro argues that the qualitative re-organization of common Romance was not simultaneous with the loss of quantitative contrasts, but that the latter were brought about by Open Syllable Lengthening. In effect, the following correspondences () between Latin and common Romance can be observed.

. Loporcaro argues that the qualitative re-organization of common Romance was not simultaneous with the loss of quantitative contrasts, but that the latter were brought about by Open Syllable Lengthening. In effect, the following correspondences () between Latin and common Romance can be observed.