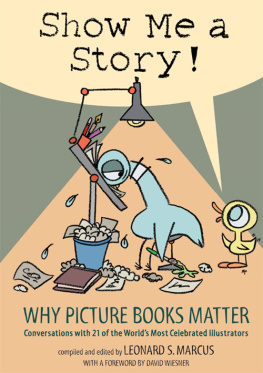

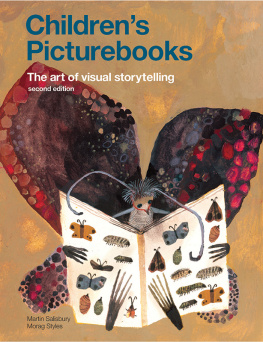

W hy do picture books matter? Of course part of the reason is because theyre books, but the heart of the matter is right there in the name; its the pictures. Before they read words, children are reading pictures. In picture books, the illustrations work in concert with the text in a way that is unique among art forms.

Picture books tell stories in a visual language that is rich and multileveled, sophisticated in its workings despite its often deceptively simple appearance. It is through the books images that a child first understands the world of the story where it is set, when it takes place, whether its familiar or new. They read the characters emotions and interactions in facial expressions and body language. They may notice secondary pictorial storylines happening alongside the main action, like a secret for them to follow. And nowhere is visual humor explored more fully than in the picture book. Possibly only Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton could equally run the gamut from gentle kidding to sophisticated wit to pie-in-the-face slapstick to anarchic postmodernism.

Such visual reading is as important to a childs development as reading written language is. Take away the pictures and you deprive kids of a wealth of understanding not to mention a lot of fun.

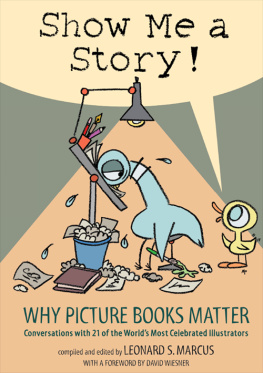

The first art that most children see is in picture books. Thats a big responsibility for the illustrator. Leonard Marcus showcases a group of artists who recognize that responsibility and respond with work that challenges and inspires kids burgeoning visual literacy. In twenty-one captivating and intimate interviews, Show Me A Story! offers an in-depth look at the passion and vision that these amazing artists bring to their work. No two are alike, except in their remarkable levels of creativity. Their books leave kids amazed and moved. They leave their imaginations energized. And quite often, they leave the kids giggling maniacally on the floor.

That is why picture books matter.

David Wiesner

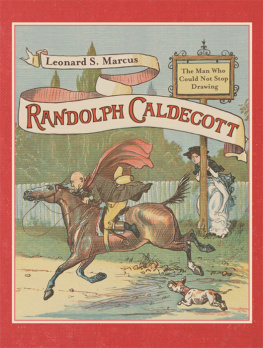

T he picture book came of age in the United States during the 1930s as the nation was recovering from the Great Depression. Americans, until then, had looked primarily to Europe for culture and to England in particular for the finest examples of illustrated books for the young. Picture books by British artists Randolph Caldecott, Kate Greenaway, Walter Crane, Beatrix Potter, and L. Leslie Brooke filled library shelves alongside those created by a small but growing number of American illustrators, including E. Boyd Smith, C. B. Falls, Wanda Gg, and Robert Lawson. As Americas industrial might grew, so did the conviction that the time had come for American illustrators to rise to the challenge of matching, or even surpassing, the high standard set by artists from across the Atlantic. It was with this ambitious goal in mind that in 1937 the American Library Association established a prize for illustration and named it the Randolph Caldecott Medal after the greatest of Englands picture-book masters.

In 1942, Robert McCloskey became only the fifth illustrator to be honored with a Caldecott Medal. It is amusing to learn that when McCloskeys editor, May Massee of Viking Press, telephoned him with the good news, the creator of Make Way for Ducklings had to ask her to explain just what it was that he should be so happy about. He had not yet heard of the medal. The episode suggests the degree to which the American childrens-book world of the 1930s and 40s remained a young and insular cottage industry. Few of the major illustrators of McCloskeys generation started out with dreams of making their names as juvenile artists. Most wandered into the field by chance. McCloskey, for instance, had wanted a career as a muralist and painter. But he needed to make a living, and because his best friend happened to be May Massees nephew, he had shown his portfolio to her. The editor, who immediately recognized his promise, gave him encouragement and a thoughtful critique. Then, sealing his loyalty to her for life, she took the young artist out to dinner.

By the time Maurice Sendak arrived on the scene less than a generation later, the situation in America had changed dramatically. Exhausted by years of depression and war, parents of the 1950s baby boom era were determined to give their children a happier, more opportunity-rich childhood than the one they themselves had experienced. They bought large numbers of books for their youngsters and supported the funding of public schools and libraries the two institutions that between them purchased the lions share of American childrens books. As the field flourished, the status of illustrators rose. In 1963, when Sendaks Caldecott Medalwinning Where the Wild Things Are first appeared, an appreciative public was prepared to hail it as a masterpiece (albeit a somewhat controversial one, with its young tantrum-throwing boy and half-scary, half-goofy alter egos) and its creator as a pop-cultural hero.

Sendaks triumph added immeasurably to the forward momentum of the picture book as an art form. On both sides of the Atlantic, more and more talented young people entered the field, among them Englands Quentin Blake and John Burningham, soon to be joined by the latters wife, Helen Oxenbury, and by a brilliant young Austrian artist named Lisbeth Zwerger. American publishers were belatedly coming to grips with the multicultural and multiracial makeup of American society and with their responsibility to publish for underserved minorities. Catalyzed by the civil rights movement, the new awareness of those years opened unprecedented opportunities to artists of color such as Ashley Bryan and Jerry Pinkney.

Such was the excitement and prestige surrounding picture books that even highly accomplished illustrators like Eric Carle (then a successful advertising artist) and New Yorker cartoonist William Steig might decide, in mid-career, to turn to the picture book as a worthy outlet for their talents. Carle took the leap in reaction to his growing disenchantment with the world of selling. To supplement his magazine income, Steig too had been designing ads, and he too had come to long for more satisfying work. In 1969, Steigs Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (which received the Caldecott Medal for 1970) and Carles The Very Hungry Caterpillar both were published landmark picture books that have not only delighted countless children but also inspired new generations of illustrators.

Carles name became synonymous with a type of picture book for which there were few historical precedents: books for children even younger than those of the traditional picture-book ages of four to eight; books that often had built-in novelty or toylike elements. His relatively brief, read-aloud stories introduced basic concepts such as counting and the days of the week in a playful way, as much by showing as by telling. At first, Americas public libraries, which had not yet committed themselves to serving the needs of toddlers and preschoolers, had no use for Carles books. But a new generation of parents quickly discovered them for themselves, as did educators at the preschools and day-care centers that were opening everywhere. As the growing demand for such young picture books became increasingly clear, more artists began to create them including one American photographer who earlier in her career had specialized in making photographic portraits of children, Tana Hoban. So too did an energetic young book designer at a Boston educational publishing house named Rosemary Wells. During the 1980s, Wells and Helen Oxenbury each produced memorable baby and toddler books salted with developmental insight, wry humor, and well-placed, knowing nods to the difficulties of being a good parent. Together, they popularized the board book as the ideal format for the youngest children, those who were as apt to yank and bite their books as look at them.