HUMANKIND

HOW BIOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY SHAPE HUMAN DIVERSITY

ALEXANDER H. HARCOURT

Dedicated to my sisters,

Sylvia, Caroline, and Elizabeth,

in memory of our many travels together.

CONTENTS

Where we are goingand why

The birthplace of humankind

A mostly coastal route out of Africaacross the world?

The science behind the facts

Where we are affects what we are

Barriers to movement maintain diversity

Human cultural diversity varies across the globe in the same way and for the same reasons as biological diversity

Size and metabolism in a small environment

Our diet affects our genes, and different regions eat different foods

Other species influence where we can live

We are bad for many species, even if we help a few

Humans are bad for each other, even if we occasionally help one another

Are we going to last the distance?

HUMANKIND

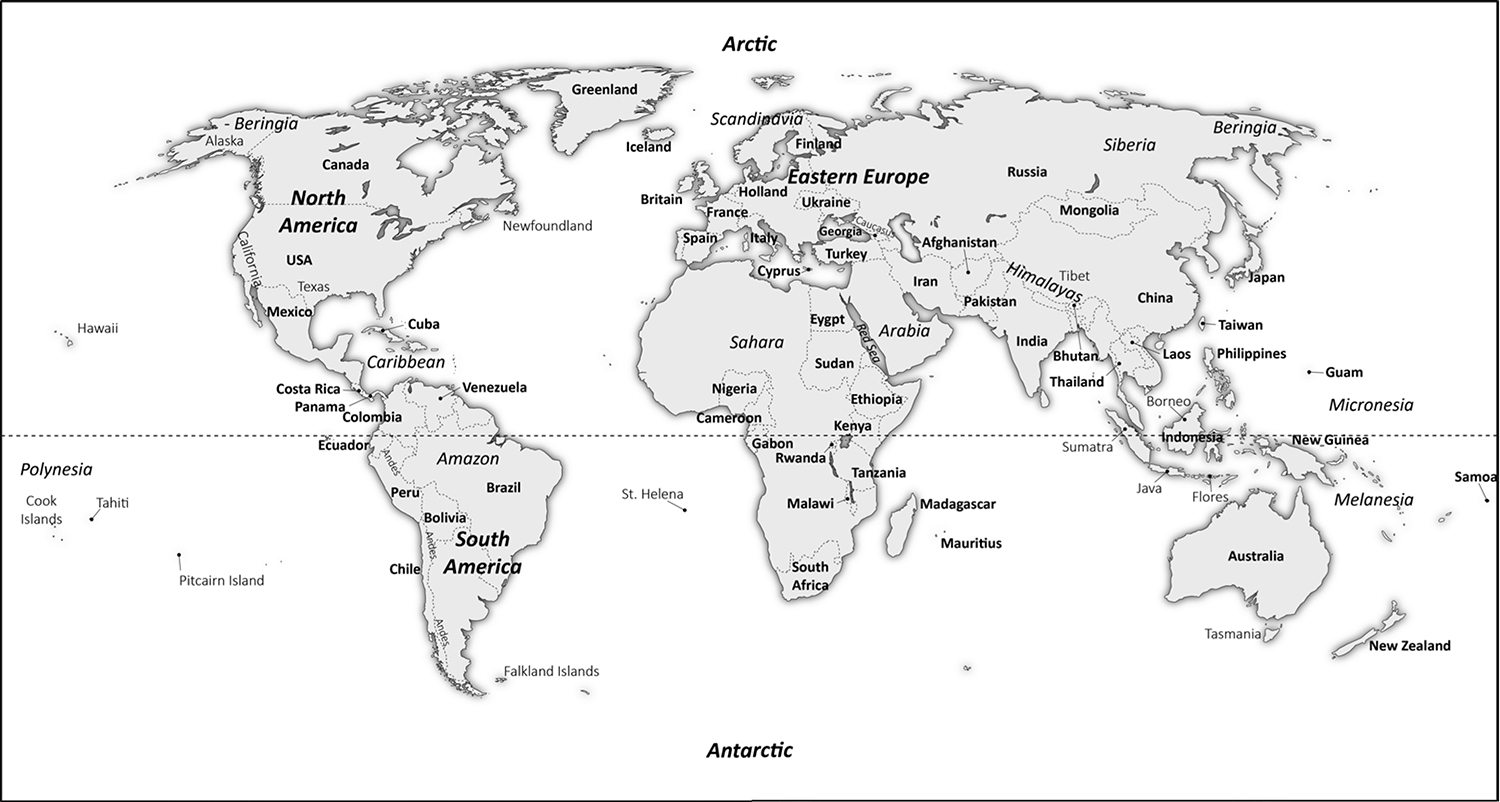

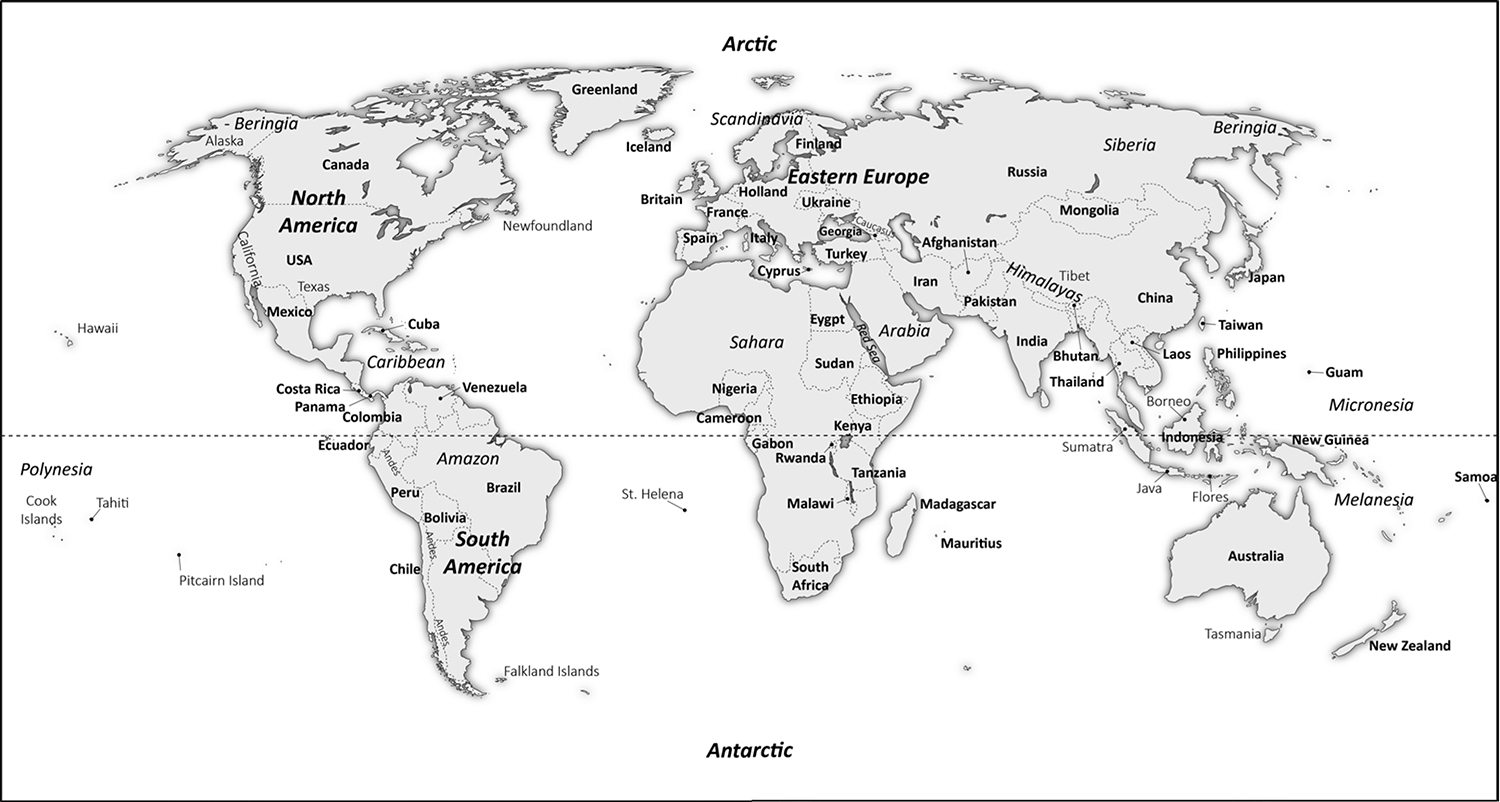

Map of the world showing regions and sites mentioned in the text. Credit: John Darwent.

Where we are goingand why

In the beginning... Genesis 1:1.

I was born in East Africa. Kenya, to be exact. Nevertheless, nobody would mistake me for a native-born Kenyan. My skin is white, because I am at the end of a long line of British-born ancestors. And if we go back far enough, I could even have a Norman ancestry. A few hundred years ago, the Normans invaded Britain1066 and all thatand in Normandy lies a town named Harcourt. In my birth country of Kenya, my father ran a cattle-and-sheep ranch. Although the peoples of over fifty cultures live in Kenya, the workers on the ranch were mostly Maasai. They were taller, longer-legged, and darker-skinned than my parents. They of course spoke a different language from us. They dressed differently. And their customs differed from oursexcept that at one time they too had entered Kenya as an invading power. My family eventually moved back to Britain, and three decades later I moved to California with my Californian wife, whom I met while working in Rwanda.

This brief description of my life history touches on several of the themes of this book: the movement of humankind across the globe, the physical and cultural differences between peoples from different regions, Western imperialism, and the great variety of cultures in the tropics. And if, for some, the mention of Africa conjures visions of the many lethal diseases of the tropics, the effect of diseases on humankind is no less relevant to the question of why we are what we are where we are.

Why are we what we are where we are? That is not just one question, it is a broad set of questions. Where did the human species originate? How did humans spread across the globe? Why do people from different regions differ? Does this variation exist because people had different places of origin, or is it because over time we have adapted to the environment in which we live? Some people have adapted to the tropics, others to cold, some to mountains, others to the plains, some to a diet of fish and meat, others to a diet of starch. What effects have other species had on the global distribution of humans? What effect have humans had on theirs? How have human populations affected each others distribution? These questions encompass much of the discipline termed biogeographyin short, the biology behind the geography of species distributions. And that is the topic of this book.

In humanitys distribution around the world, and in the biological explanations for that distribution, humans show many of the same patterns as other animals. Hence the apt title of Robert Foleys book about human evolution and ecology, Another Unique Species. All species are uniquethey would not be separate species if they were not. But as regards the biology behind our species global distribution, our biogeography, we humans are often not obviously unique. If I had adopted Jared Diamonds description of us as the third chimpanzee, and substituted modern ape for human, it might have taken some time before the reader realized that I was writing about humans.

Through the book, I write about biological and cultural differences between people who live in or come from different parts of the world. The issue of race necessarily raises its divisive head. Humans are disturbingly good at noticing differences between themselves and others, and stigmatizing the others accordingly. Consequently, some anthropologists and others do not want to recognize any biological differences between peoples from different regions of the world.

In one sense, they might be correct. Obvious as are the superficial differences between me and a Maasai man, those differences are only partial. As Darwin wrote in The Descent of Man, It may be doubted whether any character can be named which is distinctive of a race and is constant. Humans change gradually from region to region, and usually in only minor ways. Such gradual, minor change is not surprising, given Anne Stone and her co-authors finding that all humans are so genetically similar to one another that each subspecies of chimpanzee is more genetically varied than the whole human species.

On the other hand, nobody can possibly question the fact that people from different parts of the world differ biologically and culturally in various ways. Nobody would mistake me for a Maasai, just as nobody would mistake a Maasai for someone of European ancestry. The differences are real. They can be seen. They can be measured. Refusing to try to understand why people from different parts of the world are different is not going to make discrimination against others go away. It is the discrimination that we have to halt, not the understanding.

Because no character can be named which is distinctive of a race and is constant, the concept of race applied to humans is largely a sociopolitical term. Ill say here what I will describe in more detail in chapter 2, namely that we find more genetic variation within the so-called African race than we do in all the rest of the world put together. In other words, in no biological sense is there such an entity as the African race. Race as normally used is a meaningless term in the context of this book. It hides diversity. In a book that celebrates diversity by trying to understand it, the concept of race has no place.

Knowledge and understanding of our diversity can be vital in practice. Famine programs, for example, used to ship milk powder across the world as food aid. Sounds fine? No, it was not. Adults in much of the world outside western Europe and sub-Saharan Africa cannot digest milk. Worse than that, it can make them ill.

The prevalence of many diseases differs from one part of the world to another. The English doctor in the London clinic examining a west African suffering from flu-like symptoms needs to know that the patient might be as likely to have malaria as to have the flu.

The doctor also needs to know that people from different parts of the world react differently to different drugs. Given all the other differences between peoples from different parts of the world, it would be surprising if they did not. Take ACE inhibitors (ACE stands for angiotensin-converting enzyme). While people of European origin with congestive heart failure respond well to ACE inhibitors, patients of African origin do not. Luckily, another drug, BiDil (a combination of two drugs with long Latin/Greek names), does seem to work in people of African origin. Indeed, the combination apparently worked so well that the study that compared its efficacy with a previous therapy was ended early, in order that the patients receiving the previous therapy could be quickly put onto BiDil. For the moment, BiDil has not been tested on patients of non-African origin, so we do not know why it works better for Africans than do ACE inhibitors, nor indeed why ACE inhibitors do not work well for Africans.