To my daughters.

If only Id known all this sooner!

Acknowledgements

As I say elsewhere, I am not a scientist. But real scientists generously gave their time and expertise, and made this book possible.

I approached them nervously for help or advice, assuming that they would be too busy, or perhaps that they would be dismissive of a science book written by a non-scientist. Instead, I was overwhelmed by their generosity, support and enthusiasm. For their encouragement, or help, or very often both, I would like to express my huge gratitude to Professor Simon Baron-Cohen, Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Dr Stephanie Burnett Heyes, Dr Paul Ekman, Professor Susan Greenfield, Dr Murray Johns, Professor John Stein, Dr Deborah Yurgelun-Todd and Professor Marvin Zuckerman. Of course, the views I express in the book are not necessarily theirs and any mistakes are entirely mine.

If the human brain was simple enough to understand, wed be too simple to understand it.

Emerson Pugh, 1977

A note from the author:

why this new edition?

Because now we know even more than when I wrote the first edition and Im so fascinated by it that I had to tell you! I also wanted to check everything against our new knowledge. Since Blame My Brain was first published in 2005, scientists around the world have been doing more and more research, which adds to what we knew. Theres new information on emotional processing, pruning of connections, risk-taking, sleep, and alcohol and drugs. And I will introduce you to the fascinating world of mirror neurons. In short, with this edition, teenagers and all the adults who care about them can know even more about why adolescence can be such a stressful and tumultuous time, as well as an incredibly important one.

Introduction

All parents were once perfect teenagers. Model humans. Never drank, smoked, swore or lay in bed all morning. They were completely in control of all their hormones. In fact, they probably never had any hormones at all. They were calm, always smiling and incredibly polite to everyone around them.

All parents also have amnesia. Thats why they think the above paragraph is true.

They have airbrushed out the disgusting bits of their memories. The painful, greasy, smelly, hormonal, angry, nasty bits. They will tell you they tidied their rooms and filed away the days school work alphabetically before supper each evening. And brought in the coal during winter and chopped logs in the forest and sold matches on the frozen streets to make enough money for a trip to the library as a special treat. If theyd even dreamt of swearing at an adult, they would have been forced to write out five million times: I have unquestioning respect for all adults. Exams were harder and they were cleverer because there were no videos/PlayStations/computers/Internet in their day. They were all poor but happy. And on Christmas Day, their greatest joy was to play family charades. After writing their thank-you letters. Brussels sprouts? No, they didnt like them but they always ate them and appreciated their traditional importance. Sprouts are character-building.

If adults only knew the truth about the teenage brain, theyd realize that they couldnt have escaped its special behaviour. If they read this book, they might begin, gradually, to remember the truth about their teenage years. What they dont realize, and what this book sets out to show, is that the teenage brain has always been special. Different, fascinating and important things are happening inside it, which happen to everyone. Some of this is new information, or supports what scientists have recently known. Most adults will be surprised, fascinated and reassured by the contents of this book.

I want to give you a behind-the-scenes look into your own brain, so next time youre facing a row for not getting out of bed before lunch or not going to bed before dawn, for swearing at a teacher, for smoking even though its bad for you, for reacting emotionally, for taking risks, for generally being stroppy, you could just say, Dont blame me blame my brain.

Actually, none of this is exactly an excuse: its an explanation. Once you know whats going on in your brain and why, you can work with your brain instead of being so stressed out by it. Knowledge and understanding are half the battle.

You might even decide to respect your brain and treat it a bit better, once you know whats going on inside it.

Read on and be amazed.

Nicola Morgan

Edinburgh, 2013

Brain Basics

There are a few things you need to know so that the rest of the book makes sense. You need some basic facts about brains and how they work. Then, when I use a word like neuron later, youll know what Im on about. And if you forget, you can come back to this section.

BRAIN BASIC 1: WHATS IN A BRAIN?

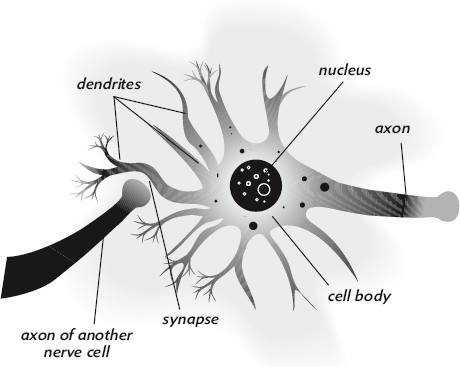

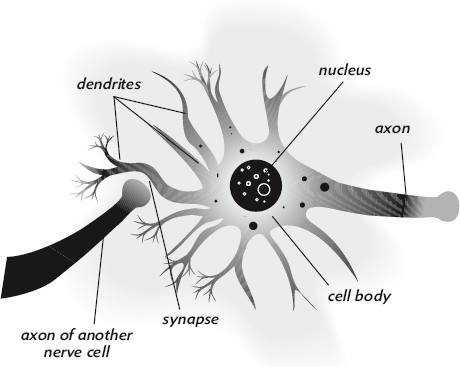

The human brain contains about 100 billion nerve cells (neurons). Each neuron has a long tail-like part (axon) and many branches (dendrites from the Greek word dendron, meaning tree). A neuron sends super-fast messages to other neurons by passing a tiny electrical current along its axon and across very tiny gaps (synapses) into the dendrites of other neurons.

If the neurons did not communicate, your body would do nothing. Every single thing you do every thought, action, sneeze, emotion, even things like going to the toilet happens when the neurons send the right messages, very fast, through this incredibly complicated web of branches.

Each time you repeat the same action, or thought, or recall the same memory, that particular web of connections is activated again. Each time that happens, the web of connections becomes stronger. And the stronger the connections, the better you are at that particular task. Thats why practice makes perfect.

But if you dont use those connections again, they may die off. Thats how you forget how to do something forget a fact or a name, or how to do a maths calculation, or how to kick a ball at a perfect angle. If you want to relearn anything, you have to rebuild your web of connections by practising again. After a brain injury, such as a stroke, someone might have to relearn how to walk or speak. That would be if the stroke had damaged some neurons and dendrites which help to control walking or speaking.

We all have different skills. The brains of a pianist and a footballer will have different numbers of dendrites and synapses in different areas of their brains.

When a human baby is born, it has almost all of its neurons. But it has few dendrites and therefore few synapses connecting them. That is why babies cant do very much. But their brains develop fast. The fastest time of dendrite development in a baby is at around 8 months. Eventually, there can be up to 100,000 dendrites on every neuron, making 100 trillion connections.

The brain is made of grey matter and white matter. Grey matter is mainly made up of neurons and you find most of it in the cortex (the outer wrinkly bit of the brain, which is only about 2 millimetres thick). White matter is mostly below the cortex and is made up of all the axons that carry messages between neurons. We could call grey matter the clever stuff. But it couldnt do very much if there wasnt plenty of good strong white matter too.