B. Pfaus

ALICE MUNRO

THE GOLDEN DOG PRESS, Ottawa, Canada

The Golden Dog Press, 1984

ISBN 0-919614-53-1

The Golden Dog gratefully acknowledges the assistance accorded to its publishing programme by the Ontario Arts Council and The Canada Council.

Printed and bound in Canada.

CONTENTS

ALICE MUNRO

It is terrible when you find out that your

idea of reality is not the real reality.

The Spanish Lady

Something Ive Been Meaning To Tell You

p. 141

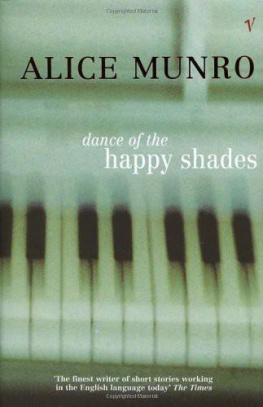

This desire to get at the exact tone or texture of how things are dominates and gives Alice Munros writing its characteristic qualities, evidenced in her 5 published volumes: four collections of short stories, Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), Something Ive Been Meaning to Tell You (1971), Who Do You Think You Are? (1978), The Moons of Jupiter (1982) and a collection of self-contained stories Lives of Girls and Women (1971), which Munro classifies as a novel. She started writing stories in her early teens aware that:

I had a different view of the world and one that would bring me into great trouble and ridicule if it were exposed. I learned very early to disguise everything and perhaps the escape into making stories was necessary.

From her early teens, she began recording in a vein of reminicent realism, the events and people of ordinary life around her in south western rural Ontario. Born in 1931, she was raised on a fox farm near Wingham. After spending nearly 20 years in Vancouver with her husband and family, she returned in 1972 to south western Ontario, Most of her stories consequently are episodic stories narrated through the wisdom and maturity of hindsight in an attempt by Munro at control over her own past experiences. Writing is for Munro:

a way of getting on top of experience; this is different from ones experience of the things in the world, the experience with other people and with oneself, which can be, which is, so confusing, and humiliating and difficult and by dealing with it, this way, though, I dont mean that I deal directly with personal experience, though I do but after quite a long time has elapsed. I think its a way of getting control.

With the writing of Dance of The Happy Shades and Lives of Girls and Women, Munro feels in control of the ghosts of her childhood but realizes that dealing with the ghosts of ones maturity is more difficult, a task she is currently undertaking.

Munro remained an obscure literary figure, publishing her stories in magazines like the Tamarack Review, the Queens Quarterly and Canadian Forum. Everything changed in 1968 when her first collection of short stories Dance of The Happy Shades, written over a period of eleven years, won the Governor Generals Award for fiction. One of the stories, Boys and Girls, produced by Atlantis Films Limited in association with the CBC, won an American Academy Award in 1984 in the Live Action Short Film category. The publication in 1971 of Lives of Girls and Women, won high acclaim as winner of The Canadian Booksellers Association International Book Year Award. The publication of Something Ive Been Meaning to Tell You in 1974 and winning the Governor Generals Award for fiction in 1978 with Who Do You ; and real feelings about things lie at the very heart of Munros writing which she works seriously at, with such pain and difficulty ten to fourteen hours a day.

When she gets an idea for a story, her first task is to find out why it feels important to her. This is a process she describes as getting it right. Most of her material then goes through five or six arduous revisions on which Munro works painstakingly slowly. There are parts of Lives of Girls and Women that have certainly been through the typewriter thirty times, she says. This process of painful revision gives her writing its characteristic compactness and delicacy of language, exactness of observation and emotional exactness....an exactness of resonance. The following passage from Images (one of Munros favourite stories) illustrates the richness of her prose style, which is often more akin to poetry with its vivid images:

The man crossed my path somewhere ahead, continuing down to the river. People say they have been paralyzed by fear, but I was transfixed, as if struck by lightning, and what hit me did not feel like fear so much as recognition. I was not surprised. This is the sight that does not surprise you, the thing you have always known was there that comes so naturally, moving delicately and contentedly and in no hurry, as if it was made, in the first place, from a wish of yours, a hope of something final, terrifying. All my life I had known there was a man like this and he was behind doors, around the corner at the dark end of a hall. So now I saw him and just waited, like a child in an old negative, electrified against the dark noon sky, with blazing hair and burned-out Orphan Annie Eyes.

(Dance, p. 38)

Behind all of Munros work is a single moral impulse exemplified by this passage that reality on its different cognitive levels must be confronted and felt, however painful it might be. Her narrators and protagonists, with the exceptions of Dick in Thanks For The Ride and Mr. Lougheed in Walking on Water are women, frequently involved in this process: trying to break out of the disguises and evasions of the conventional world into the light of truth, through the universal experience of growing up into the awareness of the complexities of human affairs and emotions which constitute experience. The frequent pain and humour of this process colours all of her writing. Actually what Munro likes best about her writing is when she has made something funny and someone laughs. I think when youve made something funny, youve achieved some kind of reality. Thats what Im trying to get.

Her stories abound with humour often subtle but always borne out of lifes ironies and incongruities. In An Ounce of Cure, the narrator recalls all the stupid, sad, half-ashamed things people like herself, in love do, culminating through disastrous innocence in her getting drunk while babysitting at the Berrymans. In Forgiveness in Families the narrator wryly comments on her brother, a sort of balding, 34-year-old Hare Krishna follower who collects welfare and calls himself a priest. Every episode in Lives of Girls and Women is narrated with Munros sense of humour: Uncle Bennys mail order marriage to that madwoman whod thrown the kettle through the window because there wasnt any water in it, and who had said shed set fire to the house because he had brought her the wrong brand of cigarettes; the day Del had bitten Mary Agnes Oliphants arm at Uncle Craigs funeral; Dels first sexual consummation not at all like the idea of a ceremonial beginning like a curtain going up on the last act of a play but, instead his belt buckle pressed painfully into her stomach, as they lean against the house, she wrestles with her panties tangled around her feet, worrying that the white gleam of his buttocks might give them away to anybody passing on the street, until they crash unceremoniously into the peony border. Just as Rose in Who Do You Think You Are? has a need to picture things, to pursue absurdities, so too, Munros comic vision is never far from, the shameless, marvellous, shattering absurdity with which the plots of life, though not of fiction, are improvised. (Dance, p. 87)

Munro defines the writing process as, a straining of something immense and varied, a whole dense vision of the world, into whatever confines the writer has learned to make for it.Marsalles in Dance of The Happy Shades, Eileen in Memorial, Uncle Benny in