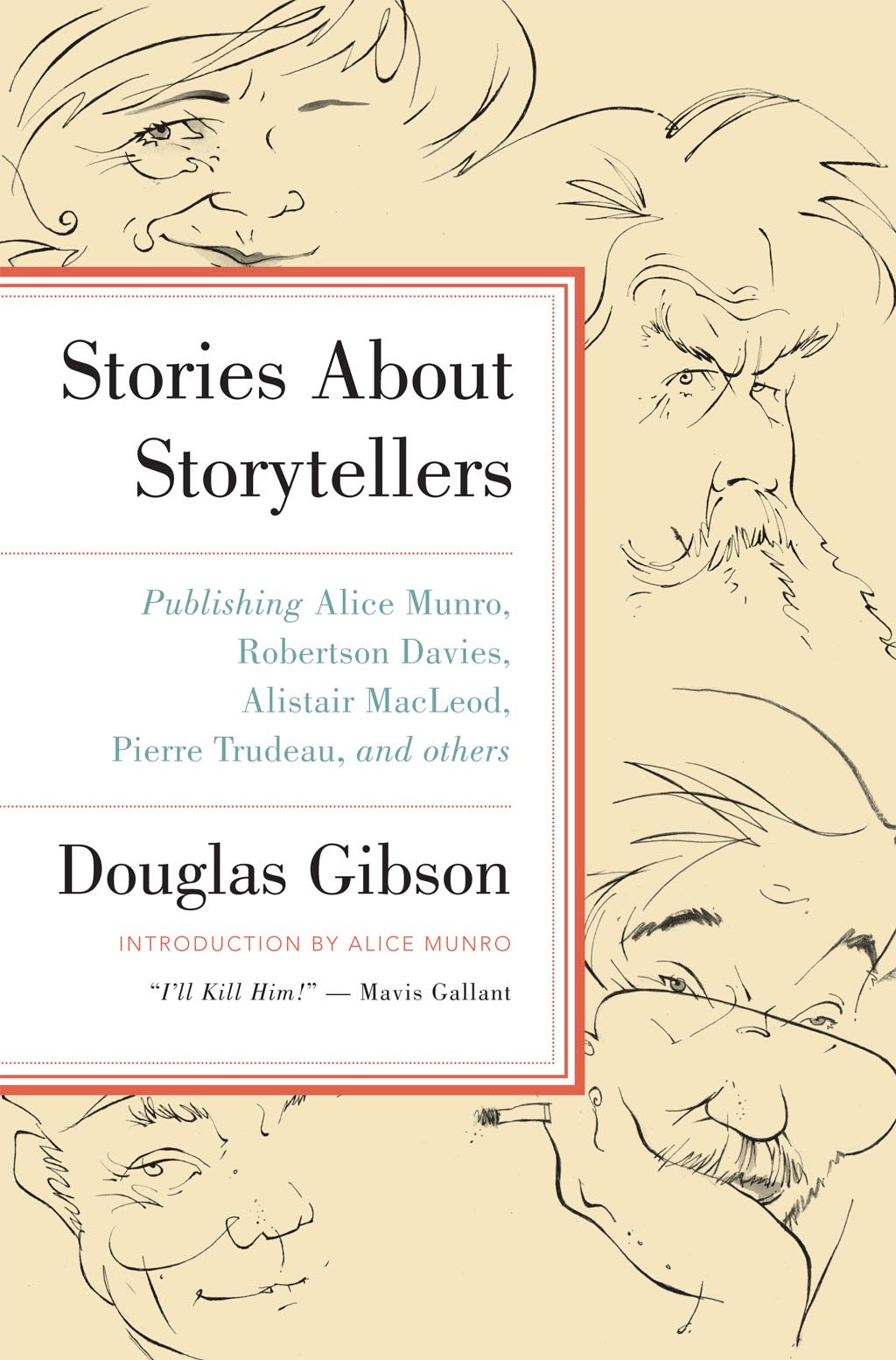

Introduction

by Alice Munro

One of my favourite things to read is a tightly packed and punchy piece of biography, or, as you might call it, biographical observation. Finding out about people who seem to have become somewhat special its addictive. Maybe we think it will become instructive. I dont know. I do enjoy it.

Some are famous, it seems, because they always knew they would be. Others wont admit they are famous at all. (These are mostly Canadians, and over .) And there are rare people who just dont notice, because they are busy all the time doing something more worthy and exciting.

Doug Gibson has met a number of these people, and tells about it in this book. He is their editor and their publisher. He tells us something about what theyre like, catching them in dire, or proud, or funny moments, when they are preparing for, enduring, enjoying, or living down whatever limelight falls on them. Hes the man who helped them to get there.

He sees them in less fateful moments, too, if they have any. He deals with them, on these pages, with lots of good humour and observes them in ways that are acute, but mostly understanding. He is not easily dismayed.

People in this book have latched onto their fame in various ways, but its the writers fiction writers that I go after. I dont care (much) who they might be having an affair with, or who theyre not speaking to, and thats a good thing, because in this book Im not going to find out. What I want to know is how they manage the separation or the lack of it between writing and life. What about their behaviour when theyre recognized in public? The dismay when theyre not? Do public readings throw them? Or buoy them up? Or both? Do they ever feel like a fraud? Is writing competing with real life or could they not tell the two things apart? Did all of them have wonderful wives? (Yes. Yes.)

And here is a digression. I am noting that nearly all of them are of the gender that has wives, and the very stroke of my pen could get grumpy, but I have to tell you this was never Mr. Gibsons fault. He was as determined to spot, harass, encourage, and publish a female writer as anybody could possibly be. There just werent many of us around.

Do I discover what Im looking for about writers, do I get some idea of the everyday, unique person? Oh, yes. Some are bare-boned organizers, while some are ready to dance on tables, often showing that strange mix of humiliation and self-exposure that makes for a bumpy life and fine fiction.

There are the writers, of course, who go around marvellously disguised as perfectly normal human beings and are not much fun. Theres another type of storyteller, too. They dont invent much. They pick up yarns and tales and pass them along as they go. Doug has some of them in his pocket as well. He has paid attention to the stories, the ways of life, belonging to those whose lives have meant a lot more to them than literature of any sort, who just like to tell you about something, then let it fall by the way.

A remarkable mix, this book.

And because of that, I have to break off from fiction, even though I believe its in every breath we draw. Even in the story sworn as true, and provided with names, about the Mean-Daughter-In-Law that I heard in Tim Hortons the other day.

We have to bow to all the non-fiction writers here as well, prime ministers and others, and to all the accounts of events that really happened and maybe even changed the world forever. And make another bow to the once-living (or still-living) amazing characters, often beyond anything youd get away within a mere story, faithfully produced in this book. As a former bookseller I know that heres what your father, your grandfather, or any other fiction-snooting fellow wants as a gift on important occasions. I have to say that the stories are interesting, sometimes compelling. Doug feels a powerful interest, and so will you. So do I.

Here I am, giving this book its due, and reading it with appetite and pleasure. How else would I ever know what the suave and delightful Charles Ritchie said to the thoroughly unpleasant Edward Heath?

So here is my prize read for people who are interested in books, writers, Canada, life, and all that kind of thing.

Thanks, Doug.

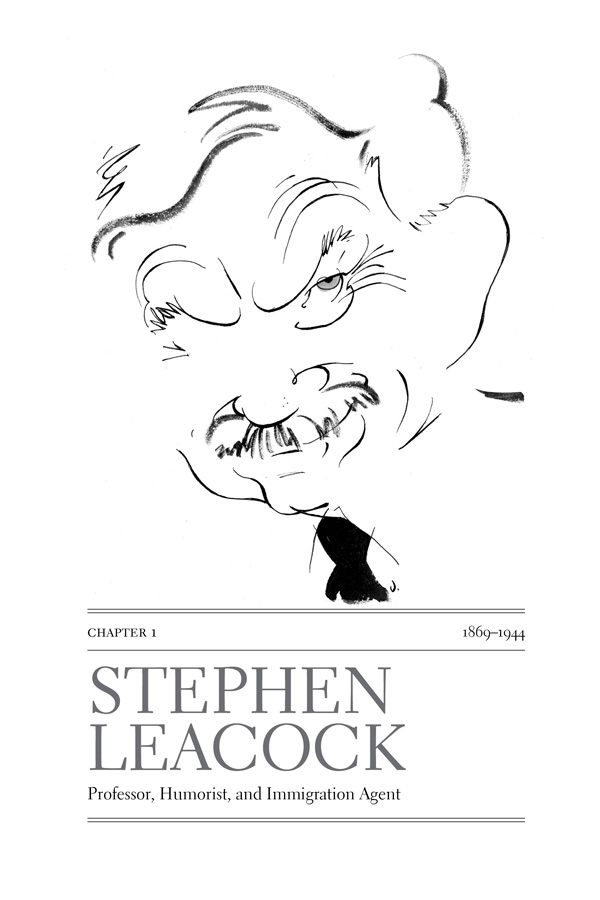

It was Stephen Leacock who brought me to Canada. Not literally, of course, for he died in March 1944, when I was only three months old which, I suppose, in a way makes us contemporaries. But his books set me giggling and snorting as a kid in Scotland spending the lunch hour sheltering from the Glasgow rain in our high schools library. There his Nonsense Novels and Literary Lapses were my favourite reading. I chortled Lewis Carrolls invented word for chuckle and snort is exactly right over people riding off madly in all directions, and at immortal lines like John! pleaded Anna, leave alone the buttermilk. It only maddens you. No good ever came of that.

I knew that Leacock was Canadian, but recognized that he had a shrewd take on Scots and Scotland, and on the attitude that had long ago produced my favourite line of old Scottish poetry, The English, for once, by guile won the day. For instance, in Hannah of the Highlands, Leacocks opening lines describe a typical heathery landscape where various Scottish heroes had rested (in one especially heroic case, pausing to change his breeches) while escaping or hiding from the English. In the course of this story Hannahs father shows his Scottish pride when he learns that she has accepted a silver coin from a member of a rival clan with which he is feuding.

Siller! shrieked the Highlander. Siller from a McWhinus!

Hannah handed him the sixpence. Oyster McOyster dashed it fiercely on the ground, then picking it up he dashed it with full force against the wall of the cottage. Then, seizing it again he dashed it angrily into the pocket of his kilt.

Later, in Winnipeg in 1982, I was to see a real-life example of such pride. Ed Schreyer had used his vice-regal position to steer the Governor Generals Awards ceremonies to his hometown, and I was there at the Fort Garry Hotel auditorium to receive the Governor Generals Award for Fiction (English) on behalf of Mavis Gallant, who was stuck in Paris with a broken ankle.

These were difficult days for federal supporters in Quebec, and the person accepting the French-language fiction award was clearly not among them. From the stage he made a fiery separatist speech, entirely in French, denouncing the event, Canada, English-speaking Canadians in general and the Governor General and the audience in particular, then showed his utter contempt for the award by taking the winners cheque and dashing it angrily into his pocket.

The unilingual audience of polite Winnipeggers applauded him warmly.

As the next speaker, I tried to rise to the occasion. I gave the first half of Maviss acceptance speech (for, as luck would have it, a book entitled Home Truths ) in my harsh French. This, I like to think, was painful to my separatist predecessors ears. Certainly, my savoir faire seemed to impress the Winnipeg audience. Polite applause again.

Leacock, of course, knew Winnipeg well. It was for that city that his father set off from the Old Homestead near Lake Simcoe with his fast-talking brother, E.P., to make their fortunes as land agents, only to return to Ontario flat broke. Many years later, after his own much more profitable visits as a speech-giving celebrity, Leacock produced his famous line about Winnipegs challenging winter climate. He noted that when a man stands in winter at the corner of Portage and Main with a north wind blowing he knows which side of him is which.