The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Introduction

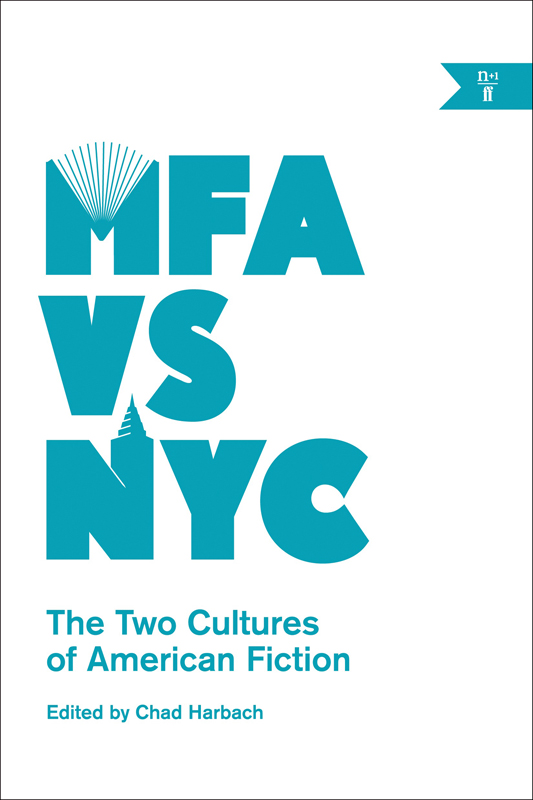

Chad Harbach

In late 2010, the essay that gives this book its name was published in n+1 Issue 10. Afterward, I received quite a bit of mail. Many of my correspondents (and coeditors) professed to have found the essay extremely depressing. Two friends living abroad, one in Istanbul and the other in London, each wrote to say that, having read my essay, they felt pretty disinclined to return to the United States. (They have both since returned.) A young woman from Korea sent several long and anguished letters about how lonely Id made her feel.

My essay proceeded from a few simple observations: First, that graduate and undergraduate creative writing programs have expanded with wild speed in the past three decades. Second, that this expansion has drawn more writers than ever before inside the university system, so that teaching rivals publishing as a percentage of writers income. And third, that this has created two centers of gravity for American fiction: MFA, which is dispersed throughout our university towns, and NYC, which hews close to Manhattans trade publishing industry. From there I tried to trace some of the social and literary consequences of this two-headed systemone in which the two heads are always chatting and bickering and buying each other drinks.

What was so depressing? In part, it may have been not the essays conclusions but its goal: that is, to consider the fiction writer less as an utterly free artistic being, with responsibilities only to posterity and eternal truth (or whatever), and more as a person constrained by circumstancea person who needs money, and whose milieu influences the way she lives, reads, thinks, and writes. A person whose work is shaped by education and economy and a host of other pressures, large and small.

A sociological approach can go too far, of course; because the writer is free on the page, and the same circumstances (not that any two people have ever lived under precisely the same circumstances) can produce an infinity of different work. But the pressures exist, always, and this book attempts to talk about them. MFA vs NYC is a book about fiction writers, and fiction writers have always existed in a messy middle ground between art and aspiration, on the one hand, and on the other, the grungy, annoying, sometimes debilitating details of reality. How much does it cost? is a key question in Austen and Balzac and Chekhov and Joyce and Wharton and Fitzgerald and Raymond Carver and Rebecca Curtis and many in between. Its not part of the job or constitution of the novelist or the short-story writer to shun the material details of the conditions within which we live our lives. The very best American novel gets under way, in its very first sentence, because its broad-shouldered narrator has little or no money in [his] purse. So he goes to see a pair of crotchety retiree investors, who haggle over his pay, settle on a very low number, and put him on a boat.

The best way to approach this book, I think, is as a kind of jointly written novelone whose composite heroine is the fiction writer circa 2014. Her voyage is a long one, and she has her frailties: her concentration is fragile, she wakes up too late and checks her email too often, she drinks too much coffee in the morning and too much wine at night. But she is always working, working, working, trying both to pay her rent and to put the way the world feels into words. Most often these tasks seem utterly incompatible; sometimes they convene and then separate again.

Our heroine, as most writers today do, attends college as a matter of course. From then forward, she may intersect with the university at many points, whether for a day or a decade, as she moves into and out of its orbit as an MFA student, PhD candidate (whether in creative writing or another discipline), adjunct instructor, guest lecturer, visiting fellow, and part-time or tenured MFA professor.

This has always existed, this affiliation between the writer and the university. Donald Hall and Ezra Pound put the case very succinctly in 1962.

HALL: Now the poets in America are mostly teachers. Do you have any ideas on the connection of teaching in the university with writing poetry?

POUND: It is the economic factor. A mans got to get in his rent somehow.

But as the creative writing industry expands, the affiliation becomes ever stronger. It also becomes more maligned. The MFA has many detractors, and many of them greatly overstate their case, harking back to a time when every writer was a wine-chugging Hemingway firing a homemade rifle at a rabid shark from the back of a speeding ambulance. (Nobody ever uses Edith Wharton, or any woman, as an example of an author untainted by degrees, though until recently women were much less likely to be degreed.) MFA writing is supposed to be sedulous, dutiful, and uninspired. And much of it ismost of it is. The problem with this argument is that these adjectives describe the vast majority of the writing that has been done in the history of the planet, but they often fail to describe the books written by graduates of MFA programs.

The MFAs defenders tend to be more knowledgeable about what actually happens in a creative writing classroom, but the return comes back with as much tricky spin as the initial serve. These defenders are generally people paid to inhabit such classrooms, and thus tend toward the rosy admissions-office view of a system that clearly has problematic elements, both pedagogic and, in its very American way of charging large numbers of students large sums to pursue a dream achievable by a few, economic.

One purpose of this book, then, is to offer a more multifarious and nuanced view of the MFA program than has previously been offered. Eric Bennett provides a foundational (and personal) history of the program that started it all, the Iowa Writers Workshop; Fredric Jameson and Elif Batuman situate the workshop and the writing it produces within larger currents of literary history; Carla Blumenkranz describes, through the figure of Gordon Lish, the complicated personal dynamics of the workshop. And a host of students and teachers, present and pastGeorge Saunders, Maria Adelmann, David Foster Wallace, Alexander Chee, Diana Wagman, Keith Gessen, and Eli S. Evansdepict and analyze their own experience on both sides of the seminar table.

New York City, of course, is the other polestar of our heroines lifeeven if she stays far away from it, it never falls far from her thoughts. Perhaps she moves to the city after college but finds her day job uncongenial to her progress as a writer, and absconds to a university town with cheaper rents. Or she attends college in the city, grows accustomed to the overwhelming niceness of Brooklyn (thats why so many writers live there: its nice), and decides the rent is worth it. At some point she sells a book to a publishing house, perhaps for a sum that seems an incredible windfalland then, as Emily Gould describes, she spends it with incredible speed, partly on clothes that go out of style, but mostly on taxes and rent.

Or our heroine never moves to New York at all, but engages with it through her book ( if she sells her book), and primarily through the peopleagent, editor, publicistwho shepherd her book through publication. Agents Jim Rutman and Melissa Flashman, editor Lorin Stein, and publicist Jynne Martin attempt to elucidate the strange and unpredictable process by which a manuscript becomes a book and a book becomes popular. One conclusion is that the people who work in publishing and the people who publish tend to begin in much the same place, with the same ambitions, and follow branching paths. Another is that the old Hollywood mantra nobody knows anything holds true for books as well.