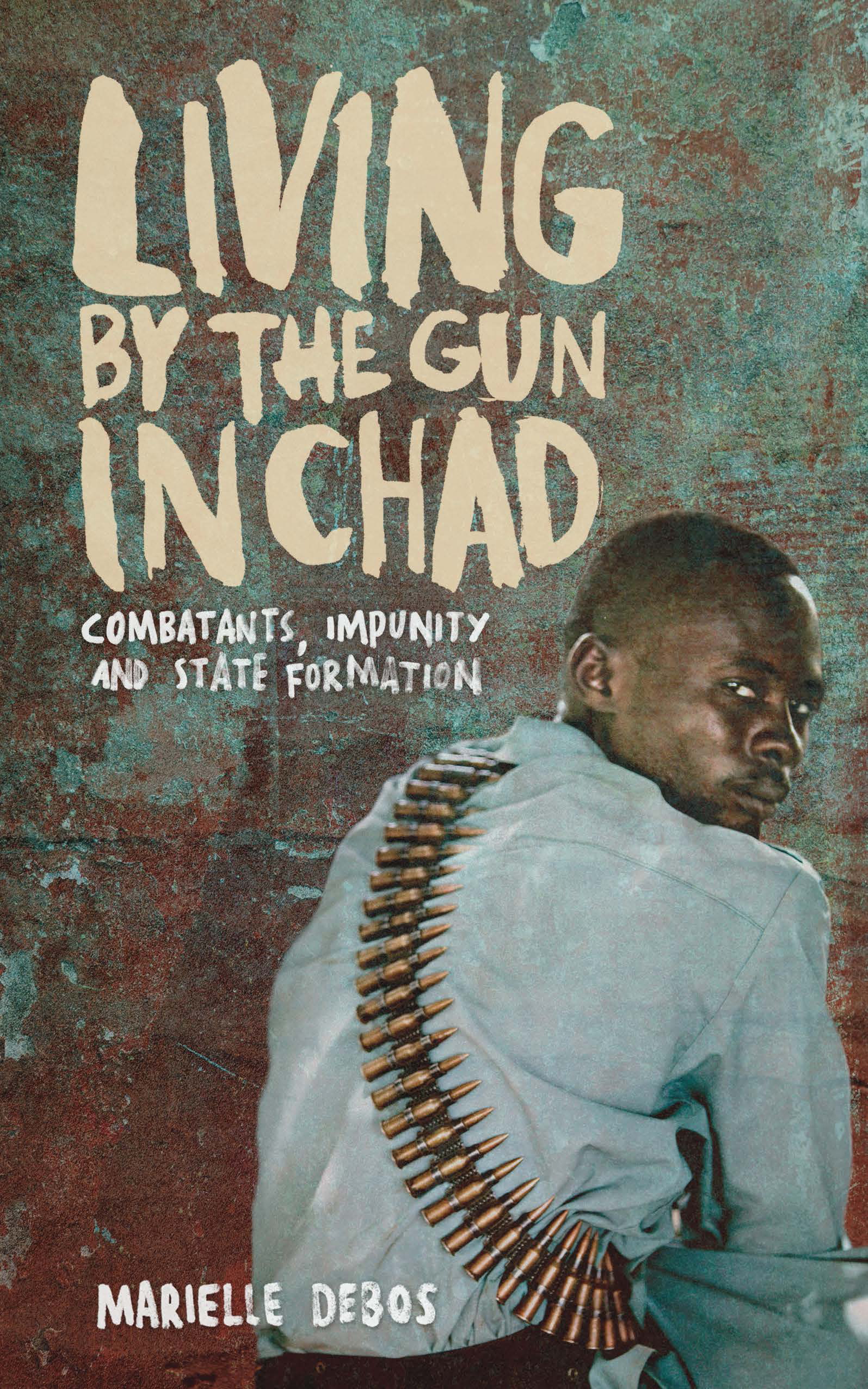

More Praise for Living by the Gun in Chad

A welcome contribution, providing a wealth of data and rare detail, resulting in new scholarly insights whose significance goes far beyond Chads borders.

Mats Utas, Uppsala University

A compelling and deeply-informed account of the militarisation of politics and society in Chad. Rather than leading to chaos, it convincingly shows how armed violence produces political order and is a crucial part of daily practices of dominance.

Koen Vlassenroot, Conflict Research Group, University of Ghent

About the author

Marielle Debos is an associate professor in political science at the University Paris Ouest Nanterre and a researcher at the Institute for Social Sciences of Politics (ISP).

LIVING BY THE GUN IN CHAD

Combatants, Impunity and State Formation

MARIELLE DEBOS

Translated by

ANDREW BROWN

Living by the Gun in Chad: Combatants, Impunity and State Formation was originally published in French under the title Le mtier des armes au Tchad: le gouvernement de lentre-guerres in 2013 by Editions Karthala, Boulevard Arago, 75013 Paris, France.

www.karthala.com

This edition published in 2016 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, Oval Way, London SE RR, UK.

www.zedbooks.net

Marielle Debos, Le metier des armes au Tchad: le gouvernement de lentre-guerres Editions Karthala, Paris, 2013

English language translation Andrew Brown, 2016 , with the collaboration of Benn Williams

The right of Marielle Debos to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 .

Typeset in Sabon by Swales & Willis Ltd, Exeter, Devon

Index by Ed Emery

Cover design by www.stevenmarsden.com

Cover photo Espen Rasmussen/Panos

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN ---- hb

ISBN -- 78360 -- pb

ISBN -- 78360 -- pdf

ISBN -- 78360 -- epub

ISBN -- 78360 -- mobi

CONTENTS

The translation of this book was supported by the Centre National du Livre, the Institute for Social Sciences of Politics (ISP-CNRS), and the Marie Curie Alumni Association.

Fieldwork was supported by the ISP as well as by the research programme No war, no peace: the interweaving of violence and law in the formation and transformation of political orders, coordinated by Dominique Linhardt and Cdric Moreau de Bellaing and funded by the French National Agency for Research (ANR).

This book is a testimony to the innumerable debts that I have accumulated over the years, starting with my debt to all the people in Chad who honoured me with their trust and shared their insights and stories. For their own safety, they have to remain anonymous. Over the course of fieldwork, three of my informants were victims of forced disappearances: Khamis Doukoun, Abakar Gawi and Ibni Oumar Mahamat Saleh. They should not be forgotten.

Since the publication of Le Mtier des armes in 2013 , a large number of colleagues have provided me with valuable comments and have helped me write a better book. Thanks to their contributions, this book is much more than just an updated version of the first one. I particularly wish to thank Richard Bangas, Gilles Bataillon, Jean-Franois Bayart, Morten Bs, Magali Chelpi-Den Hamer, Mirjam de Bruijn, Guillaume Devin, Mariane Ferme, Vincent Foucher, Laurent Gayer, Remadji Hoinaty, Milena Jaki , Louisa Lombard, Kelma Manatouma, Roland Marchal and Johanna Simant.

A special note of thanks to Andrew Brown, who translated the manuscript from French and did a wonderful job with some particularly puzzling translation issues. Justine Brabant was finally an inspiring reader and a wonderful support throughout the many rewritings of the text.

This book is an extensively revised and updated version of a book published in 2013 by Editions Karthala in Paris. It covers the inter-war of Chad: namely, those spaces and times on the margins of war and where war seems emergent. Much has changed since my first fieldwork in Chad, twelve years ago. The combatants I mention in this book have mostly abandoned armed struggle. Some have joined the regular forces, others live by the gun in a militarised economy. Most, however, have returned to civilian life and resumed their lives as farmers or pastoralists.

By contrast, Idriss Dby and his allies now live by the gun on the regional and international scenes. Dby has acquired a new status thanks to Chads military activism in the region, and the war waged by the army against the rebels is now mostly aimed at elements outside the country. The Chadian army is mobilised on several fronts in Mali and in the Lake Chad Basin. Chad, which hosts the base of the French anti-terrorist operation Barkhane, has become a key partner of France and the United States in the war on terror. The need to preserve the supposed stability of Chad encourages its allies to ignore the violence and undemocratic practices there, including the re-election of Idriss Dby in a contested election. Dby knows that his survival depends as much on external support as on internal legitimacy.

As this book goes to press, peace has become a much debated issue. During the campaign for the April 2016 presidential election, President Idriss Dby, standing for a fifth term, promised on the large posters visible on every street corner in the capital a guaranteed social peace. In response, opposition supporters and civil society activists denounced the way in which peace was being used as a form of blackmail. In an attempt to delegitimise the protests, the ruling party said that these protests constituted threats to the peace and stability of the country. A few months earlier, when civil society organisations created their platform of demands with the slogan enough is enough ( trop cest trop ), pro-government civil society responded by creating its own version, hands off my achievements ( touche pas mes acquis ). In the spirit of the creators of this latter platform, the achievements in question were peace and stability. Activists of the former platform did not fail to point out the ambiguity of the formula: the achievements could just as well be understood as profits from the oil industry, profits monopolised by a small class of political and economic entrepreneurs close to the presidency.

If the main rebel movements have now surrendered, war remains close at hand. Since NATOs intervention in 2011 , the south of Libya is a grey area conducive to all sorts of political and military adventures and every kind of trafficking. Veterans of the Chadian rebellion have congregated there. If we take their statements at face value, they are preparing for the next uprising but the initial combats have been between the different factions claiming to represent the Chadian opposition. The other borders of Chad are also crisis areas. The jihadist armed group Boko Haram has expanded its area of operations to western Chad, northern Cameroon and south-east Niger. While relations between Chad and Sudan are now good, this rapprochement has come at the cost of NDjamena abandoning its former allies in Darfur. As for relations with the Central African Republic (CAR), they have improved since the election of Faustin-Archange Touadra in February 2016 , but the question of Chadian influence on some elements of the former Slka in the CAR is undecided.