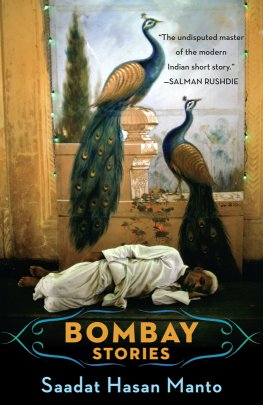

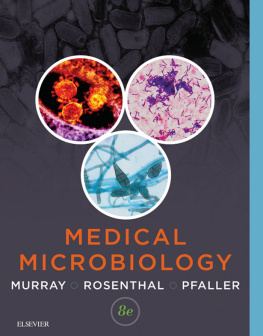

On the first morning of the training in Bombay, just minutes before she collapsed, Elizabeth Dinakar stood in front of two hundred people in the conference hall, pointed up at the cholera bacteria magnified on the wall in front of her, and said This is your enemy. The room was long and stuffy, with peeling walls and rattling air conditioners. People coughed and shuffled papers. The bacteria were the size of cars. Elizabeth Dinakar was tall and thin with thick black eyebrows. Her hair was pulled away from her face and held in a bun at the back of her head. She wore a silk shirt and khaki skirt, flat-soled shoes, and no makeup.

She talked slowly and illustrated everything she said with graphs and photographs. Every child has five to seven episodes of diarrhea a year, she said, and that is a great ocean of diarrhea. People are floating on it. She spoke as if she were reading, had a familiarity with the organisms that cause infectious diarrhea that was precise and detailed. She saw a beauty in the microscopic world that she knew others could not understand. She took it personally. As she spoke she tapped a wooden pointer against the floor. Beads of perspiration ran down her back. At the other end of the room, two stainless-steel tea urns sat on tables covered with white tablecloths. During breaks, the tea was poured into thick British Civil Service cups on saucers, and that morning she had looked over the rim of her teacup out into modern India, framed by the doors, noisy and glaring in the sun.

Blood drained from Elizabeth Dinakars face and she felt light-headed. She had begun with a discussion of cholera, a disease with its origins along the Bay of Bengal that had ravaged white-limbed British soldiers in Calcutta. Cholera is one of Indias great legacies to the world, she said, something that has struck fear into the hearts of men. She flashed a slide of a nineteenth-century lithograph depicting the specter of cholera hanging over New York City like the Grim Reaper. People at the back of the room laughed a little at this image, and Elizabeth said that it was astonishing how far they had come in just a few years; now cholera could be pinned down in the laboratory with culture, biochemistry, and antibodies. All the mystery has gone, she said, and as she spoke her voice seemed to become fainter to her, muffled, as if it were speaking from a distance. It is a conquest, she said, a conquest orchestrated by microbiologists working systematically, using solid bench science. She wondered if shesounded melodramatic, although she believed that it was dramatic; the triumph over cholera represented a triumph of the scientific method over chaos.

She stopped talking and let the pointer slip from her fingers. She turned her back to the audience. It crossed her mind that she was going to die. On the wall above her was a large Bakelite clock with a round white face and huge hands that had the appearance of sharpened harpoons. She stared up at the clock. As she lost consciousness, she saw herself as a little girl watching her father shoveling snow. She felt ice crystals on her cheeks, smelled cigarette smoke, and for an instant heard her father speaking to her. Then she fell to the floor.

A private American foundation was paying Elizabeth Dinakar to train local doctors in the principles of microbiology. She was forty years old. She had made a modest name for herself in the infectious diarrheas, studying enteric organisms that ravaged the gut. At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, she had taken charge of the enteric laboratory and now ran it as an international reference center. On her fortieth birthday she wrote Your shit is my bread and butter in large letters on a piece of computer paper and stuck it to her door. Her birthday made her feel unaccountably optimisticas if she were weightless. Nothing seemed solid. Others saw her as serious and rational, she knew. Forty years old and unmarried. Cold. She felt so different from the way she appeared that it was inexplicable to her.

A photograph of the Eschericia coli, many times life size, grainy and oval shaped, transmitted in apple cider from New England and the cause of many hundreds of cases of bloody diarrhea, sat above her desk in a thin wooden frame. She did detailed work alone at cool laboratory benches. The specimens came to her from all over the world, although before this trip to Bombay, she had never been to Asia or Africa. When she saw the cholera Vibrio, she imagined herself on the island of Celebes in Indonesia, the origin of the seventh pandemic, floating on a colorful reef, smelling sea salt and green bananas. Her thesis, on the Shigella strains causing dysentery in Africa, made her think of salty goat butter in tiny cups of acrid Ethiopian coffee, the bottomless waters of Lakes Victoria and Tanganyika, humming with Nile perch, and tall lean men walking in low scrub with hardwood staves.

She opened her eyes and for a few seconds did not know where she was. A group of men from the front row had her by the shoulders and ankles and were carrying her out of the conference hall. The men wore cotton suits and monogrammed ties, smelled like fruity aftershave, and were all talking at once. They had shiny faces. They carried her outside and laid her on a wooden bench under a row of mango trees. It was cooler under the trees and dappled sunlight came through the leaves. She blinked and tried to sit up, but they held her by the shoulders.

Raj Singh, who worked for the NGO in Bombay that was organizing the training, knelt on the ground beside her and put two fingers on her wrist. He was a small man with fat cheeks who wore spectacles that made his eyes swim like fish in a tank. She saw her own face reflected in the lenses of his spectacles.

Thank goodness. Thank goodness, he said. Her heart, it is beating quite vigorously. This is surely a good thing. Beads of perspiration clung to his forehead. He had a thin black mustache running horizontally across his top lip.

Im sorry, Elizabeth whispered.

Please. It is I who should apologize. It is too hot. Someone handed him a wet handkerchief and he pressed it to her forehead. Drops of cold water ran into her ears and down onto her neck.

This never happens to me, Elizabeth said. I dont get sick.

Your coloring is getting better. I am thinking that you fainted.

We should go back inside, Elizabeth said.

Please. Raj Singh wiped his forehead with the back of his hand. People are having tea break. There is no urgency.

Im wasting time, she said.

Please. This is no time for heroics. Look up at the mangos and think pleasant thoughts. Please.

The men stood under the trees with their hands behind their backs like benevolent uncles, periodically bending over to look at her face. Elizabeth felt awkward and self-conscious. She would rather have been alone under the trees. She did not think herself worthy of the attention, was already feeling guilty, planning what she would have to do to catch up in the conference hall.

One of the conference attendees came outside to see her. He was carrying a Samsonite attach case. He put the case on the ground, snapped it open, and pulled a stethoscope into the air, like a conjurer. The tubing of the stethoscope was black and shiny. He listened carefully to her heart and neck, and then pulled a blood-pressure cuff from the attach case with a flourish and wrapped it around her arm. He had fleshy hands. His breath smelled like tea and there were tiny splashes of milk on the front of his shirt. When he had taken her blood pressure lying down, he got her to sit up and then took it again. He said, Splendid.