H E R R I N G T A L E S

This book is dedicated to the following trio:

Maggie,

Alasdair,

and my late aunt, Bella Morrison, ne Murray, 191483, for her years of love and self-sacrifice.

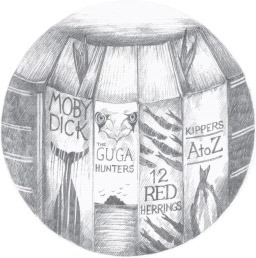

HERRING TALES

How the Silver Darlings Shaped Human Taste and History

Donald S. Murray

Illustrations by Douglas Robertson

Contents

HERRING

There are patterns in the scales which tell

how many years since they were spawned;

how many seasons they have circled;

how often they have swum through storm

and calm, slipping beyond the links and coils

thrown out from a vessels side or stern.

And each year they must count their chances

(that thought streamlining through their heads)

whether passing through tight channels

or straits where shoals are often brought or led.

Or while they race through deeper waters,

quicksilver over ocean beds,

wondering if their track is clear

or if theyll be reined by fishing nets.

I know of a cure for everything: salt water... Sweat, or tears, or the salt sea.

Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen), Seven Gothic Tales

Them Belly Full

The ghost of Marley Bob, that is, not Jacob has done his share of haunting me during my times at sea.

On a particularly ferocious trip from south Harris to the far western isle of St Kilda, his songs spun on a continual loop, played by one of the yachts crew. I was reassured by continual reminders not to worry about a thing, while the waves crashed, thunderous and white around me, lashing the back of my life jacket, rendering me wet, cold and miserable. I looked out into the blackness of the skies and heard the words of Exodus echoing, the beat of the song a frenzied rhythm through the darkness. The lyrics made me long for the solidity of earth, even wilderness or desert, anything except this constant pitch and roll beneath my feet.

On this occasion, the waters soothed me almost as much as the music of Mr Marley. I was part of a group travelling on the Atloy , an old, restored fjord steamer from the 1930s, from the western Norwegian port of Flor to a fish restaurant located in a converted warehouse in Knutholmen one of those rare places where the menu matches the magnificent setting. Accompanying the thrum of the engines was the voice of Michael, the lead singer of a Marley tribute band called Legend, which had come all the way from the Caribbean via, give or take a generation or two, the city of Birmingham, United Kingdom. With his backing group, the aptly named Elaine Smiler and Celia Heavenly, joining in the lilting harmonies, he kept instructing people not to rock the boat.

The ferry companies of the world should employ this band because, true to their word, the Atloy did not rock. It barely trembled, steaming calmly around the small islets and cliffs that are to be found on the west coast of Norway, untroubled by any of the strong winds that so frequently haunt us in the north. It was a glorious day, made bright and special by the company I kept, including the extraordinary figure of our Norwegian host, Per Vidar Ottesen, who sang Buffalo Soldier while decked out in a jacket stitched together from the bright green, yellow and red colours of the Marley flag. Like a Cuban revolutionary, a beret marked with a crimson star was perched upon his head.

There was, too, an Irish band who called themselves Tupelo, after a town in far-off Mississippi and the birthplace of that other musical giant, Elvis Presley. To add to my musical and geographical confusion, the first song these young Irishmen played later that evening was called Down to Patagonia, the southern, snow-smothered edge of the world. Its chorus boomed over the narrow streets of Flor where a crowd of Filipinos, Americans, Swedes and visiting Norwegians had gathered to celebrate the herring, the fish that provided the most important reason for this community ever coming into existence. As both visitor and native stamped their feet and joined in with the singing, I could not help but look around the small island town to see how the most important meal of my childhood had been marked within its boundaries.

Reminders of its existence were everywhere. Flors municipal crest carried echoes of that of my hometown of Stornoway, the largest community of the Western Isles. Just like the one to be found in our town hall, Flors crest was decorated by three herring, but there were important differences. These herring swam on a simple red background; Stornoways biblical injunction Gods Providence Is Our Inheritance was not scrolled below. Nor did the fish share their space on the shield with a castle or the birlinn, the single-masted vessel associated with the Western Isles and the West Highlands of Scotland. The Flor herring swim in a trio, slimmer than their Hebridean counterparts.

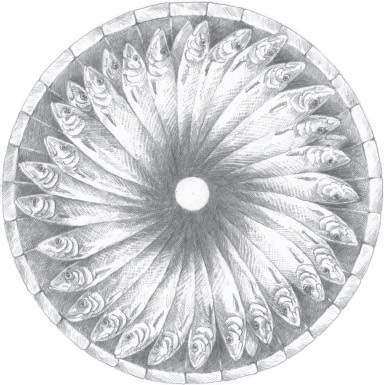

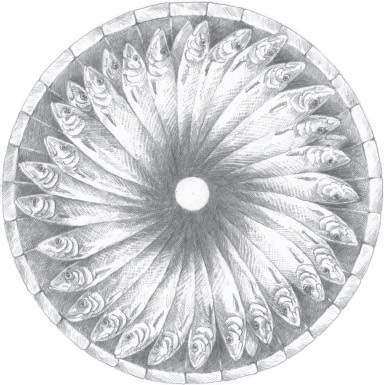

On the towns edge, too, a circular steel statue stood. With tiny jagged teeth, it was meant to resemble the open mouth of a fish but could just as easily have been a visual metaphor for the opening scene of a bad horror movie or a toothy version of the Rolling Stones logo. Atop a huddle of stone was the iron silhouette of a fisherman. One hand stretched out, the other dragged his catch by its gills as he marched onwards. A stone sculpture of a woman with a creel on her back stood not far from the towns municipal buildings. Determined to defy the wind that must so often whistle down the street, she ignored the young, bawling child who plucked at her skirt. Elsewhere, two oilskin-capped young faces grinned at people from a stone plinth. An odd-looking boy with a cap and short trousers dangled a clutch of herring in his hand, as if he were taking it home for his grandmother to fry. (She sat elsewhere, a stout, grim-faced, elderly woman occupying her own stone stool in one of the few sculptures in the town that appeared, at first glance anyway, to have little connection with fishing.) There was also a ring of herring carved from stone, circling endlessly a tiny space beside a glass-fronted office. Later that evening, as the few short shadows of midsummer fell, electric light gleamed from below the sculpture, its brightness catching and illuminating the underbellies of the fish. One could imagine how it might appear in the gloom of midwinter, as luminous and elusive as the shoals that once circled the waters of the North Atlantic and beyond, well outside the nets of men fishing at sea.

And then there were the tables that lay stretched out on the Strandgata, the towns main street. Bare throughout much of the morning, they were then draped with blue plastic sheets resplendent with the words Norway Pelagic. On the benches alongside, people crammed and squeezed, their places at the table watched jealously by those who had come late to the party, arriving, perhaps, by the National Road 5

There was certainly enough herring available to grant both spice and substance to that boast. It arrived in many forms and flavours, far more than the narrow choice of varieties I had witnessed in my youth. It was dipped in mustard; mingled with nuts; given added zest and flavour by tomato; mixed with red and white onion, carrots and herbs; sprinkled with spice; served both sour and sweet (with sherry); cooked in curry. (I missed out on the last.) For an hour or two, until people had scraped their platters clean, it seemed as if the whole town had been restored to its glory days in the middle of the nineteenth century, when both ports and harbours were awash with what men in Scotland termed the silver darlings, or what those in Norway called the gold of the sea. This was riches indeed, both a transformation and a celebration of Flors history as a place where the herring was brought ashore, albeit without the screech of gulls as used to be the case, and with condiments and seasoning not employed by the townsfolk when the industry was at its height.

Next page